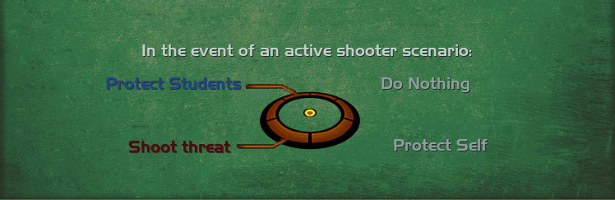

“For girls” has always been somewhat of a cringe-inducing term for me. When combined together, these two seemingly innocuous words form a concept that is loaded with a long history of stereotypically gendered marketing and the perpetuation of gender norms. It dredges up the distinct childhood divide between the “boys” aisle with its action figures and Legos aplenty and the “girls” aisle with its almost blindingly pink and purple offerings of fashion dolls and princesses. It calls to mind long lists of needlessly gendered items and products. When used in discussions of video games, it generally refers to casual games: dress up games, games about taking care of cute animals, social games and advertisements or displays like this one that floated around the internet some time ago. So when I saw that Nintendo had begun a campaign targeted directly at women and girls entitled “Nintendo 3DS for Girls,” I was more than a little skeptical.

Although my Japanese comprehension is limited, from what I can tell, the “Nintendo 3DS for Girls” campaign is one intended to make the Nintendo 3DS and its arsenal of games more appealing to a female audience. Everything is designed with a “cute” aesthetic in mind. The featured 3DS skins are largely pastel and feature adorably dainty patterns. The games they feature, including Animal Crossing: New Leaf and a design simulation game names Girls Mode 3, tend to follow a similar aesthetic to the handhold consoles Nintendo advertises as playing them. With mostly simulation and casual, social game selections, it seems that stereotypical ideas of what games appeal to girls or what games are more fitting for girls went into the making of this campaign.

To be honest, the designs of the 3DS skins and the games themselves are not the problem. I like many of the new 3DS designs and definitely enjoy them more than the standard color choices. It’s also a well-known fact that I, like the doodle of the woman ignoring sleep and other duties to play, have spent an almost ridiculous amount of hours playing Animal Crossing: New Leaf, and the rest of the games don’t seem all that bad either. If they ever get localized, I might even be interested in playing one or two. I also can appreciate the general idea of trying to attract more women and girls to gaming by addressing their gaming needs, wants, and concerns. But by designating these new 3DS models and these games as the “for girls” option, Nintendo is not only overlooking and trivializing their already existing female player base but ignoring our diverse gaming and aesthetic preferences and interests.

Although likely not intentional, Nintendo, with this advertisement, has conveyed two disappointing messages. The first is that women or girls were not already a regular or large portion of their audience prior to this sort of advertising. There is no “for boys” section of the Nintendo website filled with games and 3DS skins they think are appropriate for boys. Although I disagree with gender-targeted advertising on principal, the absence of a male equivalent of this campaign draws to light the fact that, in Nintendo and in gaming as a whole, boys and men are the norm; that women and girls must be targeted in different ways, as if women and girls don’t play games for the same reasons men and boys do.

The second problem rests in the fact that Nintendo here, with their game selections, is falling under the same vein (albeit less blatant and for an older audience) as the display I linked to earlier. While the selections are certainly not as stereotypical as the Bratz game, the Hannah Montana game, or Cooking Mama, inclusions of obscure and low exposure games like Girls Mode 3 partnered with a large portion of other more causal games rather than some of the 3DS’s many blockbusters gives off the impression that a female audience is better off reached with niche games. Why feature PoPoLoCRoIS, an RPG game that appears to star a male protagonist with a limited female cast, when Fire Emblem Fates lets you play with a female avatar and stars a rather large female cast? Why show a variety mini game collection when you can feature women playing female characters in Super Smash Bros.? Or younger girls playing a Youkai Watch game with the female avatar option? Or even just women or girls playing Super Mario 3D Land?

This is not to say that there is anything wrong with the games they featured – as I mentioned earlier, I’m sure they’re probably fun. But they’re stereotypically predictable choices for what advertisers think girls might like to play. There’s a fairly good deal of diversity in Nintendo’s games that matches the diverse interests of their players. So it’s a shame that instead of using this diverse and creative lineup to attract perspective or current female gamers, this campaign seems to restrict female gamers to certain types of games.

One thought on “Designed “For Girls”: The Problem with Nintendo’s “For Girls” Campaign”

Your point about the campaign assuming that women and girls aren’t already involved in gaming reminds me of the attitudes of many Opera Houses to the working class.

There was always something that bothered me about the campaigns by certain opera houses to get more working class people through their doors and I couldn’t really put a finger on what it was until a friend made a similar point to that which you make about this nintendo campaign.

The opera houses were operating from the assumption that there was a real and irresolvable conflict between ‘high culture’ and the working class. Their campaigns assumed that any contact between the two would be tentative, temporary and cross-cultural…like the interaction between alien species who could never really understand each other. They would consequently advertise in a patronising manner, pointing out those operas with the simplest plots, or that were in English, rather than assuming that perhaps the art they produced could say something to everybody.

Not only did these campaigns highlight their own beliefs on the matter but it reified the fear felt by people unfamiliar with opera, the target audience, they saw the campaigns, the operas that were advertised and saw their own fears confirmed: “Ah yes opera must really be something that is not for me, otherwise why would they only be advertising these simple English operas”, or “opera must really be something very formal if they have to point out that these events don’t have a dress code”.

It seems to be a pattern that exists wherever organisations attempt to communicate with groups they believe to be outside of themselves. It is also a big problem in academia when communicating ideas to ‘lay people’.