This week I played The Beginner’s Guide, the latest effort from Davey Wreden, creator of the much-lauded The Stanley Parable. The Beginner’s Guide, much like that game, is a short experience, built in Source, and as The Stanley Parable is a commentary on agency and game design, The Beginner’s Guide has much to say about authorship, ownership, and the balance of creation-for-creation’s sake against creation for audience.

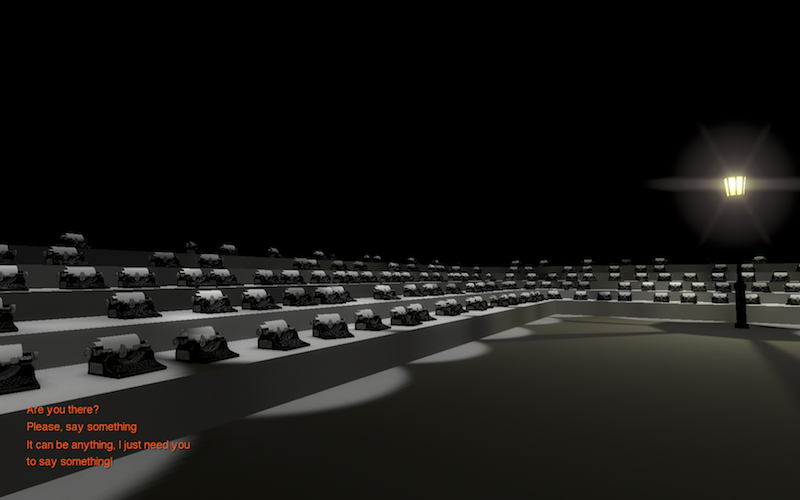

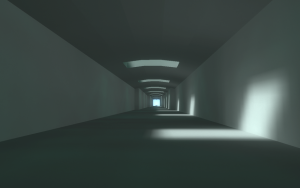

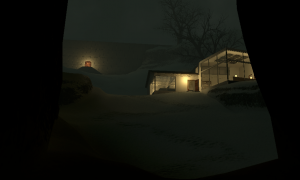

Ostensibly, The Beginner’s Guide is the story of Coda, a game developer Wreden met at a game jam, and an exploration of Coda through the games the shared with Wreden between 2008 and 2011. As the story unfolds, we watch Wreden critique these short game experiences, unraveling meaning in such symbols as labyrinths, prison bars, and fragmented notes left by players who don’t exist. Wreden reveals eventually that he was worried about his friend, or his friend as he viewed them through these games; felt like Coda was trying to work something out, so maybe a closed-door puzzle signified an ending in one section of Coda’s life, a closure on something. Maybe the space between doors, an empty, peaceful darkness, was an escape, a momentary respite. But as the narrator says, “Sooner or later you have to pick up and move.”

Ostensibly, The Beginner’s Guide is the story of Coda, a game developer Wreden met at a game jam, and an exploration of Coda through the games the shared with Wreden between 2008 and 2011. As the story unfolds, we watch Wreden critique these short game experiences, unraveling meaning in such symbols as labyrinths, prison bars, and fragmented notes left by players who don’t exist. Wreden reveals eventually that he was worried about his friend, or his friend as he viewed them through these games; felt like Coda was trying to work something out, so maybe a closed-door puzzle signified an ending in one section of Coda’s life, a closure on something. Maybe the space between doors, an empty, peaceful darkness, was an escape, a momentary respite. But as the narrator says, “Sooner or later you have to pick up and move.”

Throughout, the player experience is heavily guided by the narrator, who solves puzzles and skips through whole sections with a bit of hand-waving explanation, because the point isn’t to experience any of it yourself, but to get to the next aspect of the story, the critique. Actual play, as we usually understand it, is limited; yes, we pull some levers, and we can choose dialogue options at times, but our interaction is very controlled and always in service to the narration, which is primarily what intrigues me about the experience.

That’s all I can really say without spoilers, as there’s no way for me to analyze The Beginner’s Guide as a game without talking about what happens within it, and how, so this is a good time to go play or watch the game if you haven’t yet.

As the player is pushed through these little Coda-created games, the narration turns from critique of game to critique of creator. Coda seemed depressed, he says, like he was growing more and more desperate for human connection, and like something was terribly wrong. Finally, the narrator says he began to show Coda’s games around, something Coda wasn’t doing himself, so Coda would know how much everyone liked them, because that would make everything better, of course. But this was put forth with a level of sadness, so it seemed the narrator understood what a terrible breach of trust that must be, and in the final game, we learn that Coda felt the same, that he felt betrayed and he didn’t want to talk to the narrator again.

Resolution, yes? Not quite: the narrator, in an emotional monologue, reveals that this whole experience, this collection and critique, is an elaborate way to get Coda to contact him. He’s apologizing… by showing the games again, this time to a wider audience.

Of this moment, Laura Hudson wrote she “felt ill, even angry after this revelation. It seemed like the game had made me unknowingly complicit in a huge violation of someone’s privacy, one that I had no way of undoing.” I, too, was furious and disgusted; for a moment, I actually considered seeking a Steam refund. But the monologue quickly ratcheted up the melodrama, and I began to question. Was this real? Or was the whole experience an extended metaphor? I had suspicions, and like Hudson, upon later reflection, I quickly became convinced it was closer to the latter, that, as Hudson wrote, “rather than an estranged friend of Wreden, Coda makes more sense as an elaborate metaphor for every game developer who has to contend with overinvested fans, while ‘Wreden’ steps into the role of the players and critics who insist that games conform to their desires, endlessly demand answers about a ‘deeper meaning,’ or worse, insist that they and they alone can peer through the window a game supposedly offers into the developer’s soul and discover the truth.”

But I wasn’t quite as sure as Hudson about where that positioned me on the experience itself. Brendan Keogh, in writing of the game, cuts right to the heart of my frustration not with analysis, as he says (though I agree with him), but about the approach of The Beginner’s Guide itself. Keogh says, of critiques on games with clear themes (he uses examples such as This War of Mine) “they are games that I guess I don’t think require any thematic analysis. It’s pretty obvious what they are doing! Analysing how they do these things is still worthy (the difficulty of desk space in Papers, Please, for instance) but simply pointing out that The Stanley Parable is about choice just seems… boring and easy.”

And that, in a nutshell, is how I feel about The Beginner’s Guide itself. The narration, and its focus on audience interpretation of basic symbols and ideas — and possibly incorrect interpretation, down to attempts to diagnose creators’ mental health — just seems easy (though I wouldn’t call it boring). It seems to precisely replicate the blog post Keogh linked by Wreden, which is followed by a comic he created on the same subject. So Wreden created a comic, wrote a blog, and created a game, all to work out these same struggles after The Stanley Parable. And let me be clear before I go on: I’m not in any way attempting to delegitimize Wreden’s feelings, or say that he shouldn’t work those feelings out in a variety of ways. But it does make me question whether or not The Beginner’s Guide is a game at all, or just a visualization of that blog post… and I’m not sure the game, if it is one, is the subversion of the ideas within it that it was meant to be, but for my purposes here, that’s a secondary question, one I may address another time.

In order to determine whether or not The Beginner’s Guide is a game or just a piece of writing, like any essay or story, we have to establish some parameters for games and play. In Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga offers a long look at play, summarized as follows: “Play is a free activity standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as being ‘not serious,’ but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. It is an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained by it. It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner.” While I have a lot of issues with Huizinga’s definition — most, but not all, relating to how play has changed over time and how little this definition continues to fit the contemporary — it does give us a good place to start.

Raph Koster, in talking about what games are, and what they aren’t (in a real-world sense, anyway, not in the sense of the potential of games), says games are about training players to recognize mathematical patterns. He also says, “games are not stories. It is interesting to make the comparison, though:

Raph Koster, in talking about what games are, and what they aren’t (in a real-world sense, anyway, not in the sense of the potential of games), says games are about training players to recognize mathematical patterns. He also says, “games are not stories. It is interesting to make the comparison, though:

- Games tend to be experiential teaching. Stories teach vicariously.

- Games are good at objectification. Stories are good at empathy.

- Games tend to quantize, reduce, and classify. Stories tend to blur, deepen, and make subtle distinctions.

- Games are external – they are about people’s actions. Stories (good ones, anyway) are internal – they are about people’s emotions and thoughts.”

Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, in Rules of Play, define a game, on the other hand, in a broader sense: “A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome.”

Three very different definitions, which when mashed together, might give us a rubric that looks something like this:

Games and play will reflect most, but maybe not all, of the following characteristics:

- an activity outside ordinary life

- not “serious,” which we’ll define here as not being essential for survival (though this is at the root of some of my issues with Huizinga)

- includes fixed rules

- a quantifiable outcome

- absorbs the player

- external reflections of actions (not internal reflections of emotions and thoughts)

- privileges objectification over empathy

- learning experientially rather than vicariously

- includes artificial conflict defined by rules

Arguing the first will quickly find us in the realm of semantics; yes, in replicating the player/creator relationship, The Beginner’s Guide is reflecting something very ordinary, but moving through the narrative experience is inherently outside normal life because it’s an experience that must be entered. So, yes, TBG meets this characteristic, which is why it’s been rendered in pink. TBG is not essential for survival, so the game passes criteria #2 (though perhaps not if we define “serious” in any other way). Yes, there are fixed rules (TBG is a fairly linear experience), there is a quantifiable outcome (eventually the credits roll), and it certainly has the potential to absorb the player. So far so good; TBG looks like a game.

But many of these criteria can also be applied in some ways to stories — which are similarly not essential for survival and are activities outside normal life (a book must also be entered in a sense, after all). And the rest of the criteria may not fit The Beginner’s Guide at all; in fact, the entire experience sounds very like Koster’s definition of story, something he says vehemently games are not. Salen and Zimmerman’s insistence on conflict here then becomes very important. What is an artificial conflict? Because no matter how we choose to read The Beginner’s Guide (as fiction/metaphor for the creator experience, or as a true story of Wreden treating Coda terribly), the conflict at the center seems very real. So what is real here? What is artificial? Salen and Zimmerman do specify that the conflict must be defined by rules, presented as part of a system. There’s no system, in that sense, for emotions, or for our read on the game. Instead, no matter how TBG is interpreted, we are in that territory fully claimed by Koster as story. As we move through Coda’s games and listen to the narration, we are moving through a visual reflection of emotions and thoughts. We are learning the story experientially and vicariously.

Because there is no clear answer, those last items in our rubric remain in black. We cannot definitively say, yes, The Beginner’s Guide meets all those criteria for a game. So does that mean it isn’t a game? Or does that mean that these definitions haven’t yet caught up with where games are going? Koster’s piece appeared on Gamasutra in 2004 (and is included in his book A Theory of Fun), Salen and Zimmerman published their book in 2003, and Huizinga, of course, was writing decades before any of them; video games were not even a remote concern. Yet here, in 2015, we’re at times playing stripped-down story games with limited choice, experiential simulations of abuse and more, and entering experiences like this, which are structured, visual renderings of Wreden’s struggle. Is it a game? Is anything that isn’t a series of puzzles, platforms, or challenges, according to these definitions? Is it a game just because it looks like a game and is built in a game engine and has some trappings of game? Or is it more an essay, with the person undertaking the experience moving from chapter to chapter in lieu of turning pages? Is it a lecture with visual aids?

One of the most wonderful things about playing and studying games is that the medium is evolving so rapidly that our very experiences can differ wildly from year to year, but that’s a frustration, too, because as soon as we pin down one framework for studying games, something else happens. And that isn’t to say no one’s ever created anything like The Beginner’s Guide; in fact, we see game experiences like this quite often, though Wreden’s, of course, will continue to garner a lot of attention thanks to the success of The Stanley Parable. But it is that commonality that drives us to question these definitions again and again, what leads us to look up from the keyboard or the controller to ask, just what am I doing? What kind of experience am I having, and where are the lines drawn here?