There’s an innate yearning within humanity to connect, share, and make sense of our experiences. It’s more natural than secret-keeping, which is dogmatically taught to us before we learn how to string concepts and words together. So when I was asked to talk about the fact that #yesIplay, it took a little over a month to figure out how games (digital or not) influence my life – really I was trying to justify why a conversation about games was relevant for me. In my world, things must be presented logically, things must be rationalized, things must be accepted by the masses and this includes all of my life decisions. So my month of rumination was spent trying to understand how others view games and I how I fit into that communal mold. This led me to extrapolating a definition of “game” for which I could squeeze into since I’ve never identified as a “gamer.”

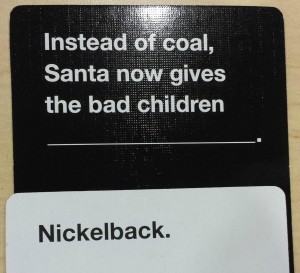

I began wondering: Does Scrabble count? Taboo? Cards Against Humanity (which I always win)? From the perspective of second language instruction, yes. Games that interact with words and the social construction of meaning are certainly beneficial when you’re embarking on teaching or learning a language beyond the borders of your home. Picture this: eight people, six of whom are international students – five speak Chinese and one speaks Polish – and then two of us whose first language is English all playing Cards Against Humanity. In this game, much of the decision making is based on the reader’s personality, knowledge of the cultural concepts being engaged, and the individual’s history. Because of this, the eight of us decided to have a safe word (it’s a downward spiral to the belly laughs of hell), so as not to offend anyone. Five rounds later, we all learned a lot with quite a bit of translation between languages taking place. I never thought I’d have to ask my partner to describe what “queef” means to my classmates who would then translate for their significant others and friends. (Disclaimer: I would not use this game in class. Apples to Apples is a good alternative though).

I began wondering: Does Scrabble count? Taboo? Cards Against Humanity (which I always win)? From the perspective of second language instruction, yes. Games that interact with words and the social construction of meaning are certainly beneficial when you’re embarking on teaching or learning a language beyond the borders of your home. Picture this: eight people, six of whom are international students – five speak Chinese and one speaks Polish – and then two of us whose first language is English all playing Cards Against Humanity. In this game, much of the decision making is based on the reader’s personality, knowledge of the cultural concepts being engaged, and the individual’s history. Because of this, the eight of us decided to have a safe word (it’s a downward spiral to the belly laughs of hell), so as not to offend anyone. Five rounds later, we all learned a lot with quite a bit of translation between languages taking place. I never thought I’d have to ask my partner to describe what “queef” means to my classmates who would then translate for their significant others and friends. (Disclaimer: I would not use this game in class. Apples to Apples is a good alternative though).

Moving beyond card games, I started pondering why I wasn’t more involved with digital games. Privilege? Assumptions? Communal understanding of what playing video games means? PTSD? My upbringing taught me that gamers were men who lived in their mother’s basements, or were unemployed, drunk, abusive fathers who threw controllers. Gamers were not girls and especially not women who are getting PhDs. So I turned to books, books that talked about things I could relate to, books that gave me an element of escape, books that humanized, reconciled conflicts, books that made me sound smart to the masses (because, unfortunately, no one asks, “So what game are you playing these days?”). It wasn’t until a couple of months ago that my perspective of gamers and identifying as a gamer shifted.

This great shift in the mind of Ashley occurred during a class in which I met other PhD students who did research on games, who played games, who liked games, who were gamers, who used games in their classrooms, and I was not and did not – at least I thought. And, so, I began exploring the use of narratives in games, how games might be used when teaching ESL (English as a Second Language) writing, and how games might affect my own personal growth as a human being wanting to connect with others. And then this exploration turned into my first purchase of a gaming console and a decent TV (I hadn’t realized I was dwelling in the Dark Ages). Yet, the entire time I contemplated buying and waited in line to buy a decent TV and an Xbox One, all I could think about was how I’d have to justify that #yesIplay to family and friends and the masses who, for some reason, look down upon those who play, whether for recreation, research, or both over those who read, knit, or brew cider. Then it dawned on me: I don’t have to justify an experience, my experience, or keep it a secret because others don’t understand. I merely share it and invite others to share theirs, too.

This great shift in the mind of Ashley occurred during a class in which I met other PhD students who did research on games, who played games, who liked games, who were gamers, who used games in their classrooms, and I was not and did not – at least I thought. And, so, I began exploring the use of narratives in games, how games might be used when teaching ESL (English as a Second Language) writing, and how games might affect my own personal growth as a human being wanting to connect with others. And then this exploration turned into my first purchase of a gaming console and a decent TV (I hadn’t realized I was dwelling in the Dark Ages). Yet, the entire time I contemplated buying and waited in line to buy a decent TV and an Xbox One, all I could think about was how I’d have to justify that #yesIplay to family and friends and the masses who, for some reason, look down upon those who play, whether for recreation, research, or both over those who read, knit, or brew cider. Then it dawned on me: I don’t have to justify an experience, my experience, or keep it a secret because others don’t understand. I merely share it and invite others to share theirs, too.

Unless you’ve […]

Unless you’ve […]