I read Jorge Albor’s “The Games I Fear to Play: Reflecting on the Personal in Games” the other day, in which Albor considers the manner in which games represent personal experiences, arguing that games “do a damn good job of instigating self-reflection.” Indeed, Albor believes that it is perfectly “reasonable to entwine personal feelings with games. We assign meaning to our actions, even at play, when we think ourselves most free.” And because of this meaning-making that occurs even at play, Albor asks, “How could gaming not trigger personal reflection? They have been channels for so much camaraderie.”

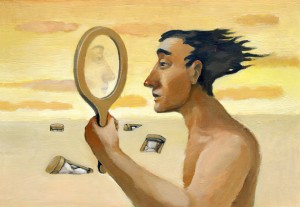

Reading Albor’s piece has led me to think about how games instigate my own personal reflection, my own experiences playing games, my own experiences writing about them. And this is actually something that I’ve been thinking about a lot lately because it’s something I struggle with—being reflective and reflexive in my own writing. But it’s also something I’m trying to make an effort to do more of because, as someone who has only recently begun working within the field of game studies, I often struggle with my own position within the gaming community—as a member of the community and a researcher of it—and I often find myself asking whether or not I am enough of a gamer or enough of a games scholar to be qualified to conduct research within the field.

Reading Albor’s piece has led me to think about how games instigate my own personal reflection, my own experiences playing games, my own experiences writing about them. And this is actually something that I’ve been thinking about a lot lately because it’s something I struggle with—being reflective and reflexive in my own writing. But it’s also something I’m trying to make an effort to do more of because, as someone who has only recently begun working within the field of game studies, I often struggle with my own position within the gaming community—as a member of the community and a researcher of it—and I often find myself asking whether or not I am enough of a gamer or enough of a games scholar to be qualified to conduct research within the field.

But I have also come to realize that such self-doubt seems to result from the manner in which hierarchical systems of knowledge production (who gets to be a knower and what gets to be known) exist within the gaming community, systems that seem to perpetuate positivist and patriarchal constructions of objectivity, neutrality, authority, and truth. As such, my hope is that, by enacting feminist research within the gaming community, and by exploring my own position and experiences within it, I might begin to help disrupt these hierarchies of knowledge and that I might work to write myself into my analysis of such hierarchies. But I’m also concerned that I’m not writing myself into my work enough.

So, I wonder how I might write myself into my work more fully and I wonder how doing so might allow me to more effectively work with others within the gaming community to disrupt the hierarchies of knowledge construction that exist there. I wonder how my own position in the community and how my position’s various levels of belongings and exclusions shape the ways I research video games and the gaming community. And I wonder how these belongings and exclusions shape the way my research often reemphasizes the need to interrogate narratives as well—but not just a literary interrogation of the narratives that exist within video games or a cultural interrogation of the narratives being constructed in the lives of those who make and produce them but the interrogation of the conversation that occurs between these different types of narratives (and more) and the manner in which I am positioned in relation to these conversations.

In order to make use of such analyses, and in order to make reflexive meaning through such research, it seems helpful to consider the fact that meaning is plural and shifting and that the manner in which meaning is made is affected by the relationship between speakers and hearers. Indeed, this awareness of the speaker/hearer relationship on how truth-value is constructed seems especially vital when working within the gaming community because it is a community (like so many others) in which who gets to be a speaker and who gets to tell truths and who gets to be believed and heard often become privileged in gendered ways. As the events of situations like Gamergate reveal, this gendered hierarchy of believability and this gendered privileging of who is allowed to generate so-called truths continue to affect the ways games are produced, what kinds of games are produced, and who gets to produce (and play, and talk about) them. As such, it would seem that an awareness of this context, an awareness of how we are all perceived as both speakers and hearers in the gaming community, might allow us to work more effectively to dismantle such structures and to strategically problematize how it is we conceive of truth, which is not located outside our interpretation of it but within these interpretations. And, perhaps, by more openly discussing my own complicated identity and experiences as a gamer and games scholar in my own work, I might help to enact such a reconfiguration—a challenging thing for which to strive, to be sure, and one that I am sure I will continue to grapple with for years to come, but something that seems worthwhile to me, despite (or, perhaps more accurately, because of) such challenges.

But reflexivity is hard. Reflection is hard. And I think for me it’s hard because of the sense of vulnerability that goes along with expressing the personal. But I think that writing about video games requires making reflexive moves because of what Albor says about them—because of the meaning we assign to our actions when at play and when thinking about our play.

But reflexivity is hard. Reflection is hard. And I think for me it’s hard because of the sense of vulnerability that goes along with expressing the personal. But I think that writing about video games requires making reflexive moves because of what Albor says about them—because of the meaning we assign to our actions when at play and when thinking about our play.