Last week, around the same time that I started playing Anatomy, my sister turned me onto The Black Tapes Podcast, and, as a result, I’ve been thinking a lot about the game and the podcast concurrently. As Gavia Baker-Whitelaw puts it, The Black Tapes Podcast is framed “as a Serial-esque series hosted by reporter Alex Reagan” and “feels like what might happen if a perky NPR journalist decided to investigate the Blair Witch Project.” And, Baker-Whitelaw continues, the premise for this serialized docudrama goes a little something like this:

Last week, around the same time that I started playing Anatomy, my sister turned me onto The Black Tapes Podcast, and, as a result, I’ve been thinking a lot about the game and the podcast concurrently. As Gavia Baker-Whitelaw puts it, The Black Tapes Podcast is framed “as a Serial-esque series hosted by reporter Alex Reagan” and “feels like what might happen if a perky NPR journalist decided to investigate the Blair Witch Project.” And, Baker-Whitelaw continues, the premise for this serialized docudrama goes a little something like this:

The Black Tapes Podcast was originally billed as a profile of paranormal investigator Richard Strand, a character partly inspired by the real-life skeptic James Randi. But things take a turn for the disturbing when Reagan discovers Strand’s file of unsolved cases, the so-called Black Tapes. Despite his best efforts, Strand hasn’t been able to find a scientific explanation for this unsettling collection of seemingly supernatural events.

Even though the podcast is fictional, Reagan’s “interviews with witnesses and academic experts feel so realistic that some listeners fail to realize that the podcast is a work of fiction. In the vein of the icon of audio drama Orson Welles’ The War of the Worlds, the best kind of horror story is one that you can almost believe is true.”

Molly Osberg, too, takes up this idea of believing in the podcast’s truth or reality, arguing, “The whole thing is so spot-on that you might be forgiven if, like some of the gullible listeners who mistook 1938’s War of the Worlds broadcast for an actual alien invasion, you take them at their word at first.” But the creators of the podcast also seem to ask us to take them at their word for longer than just “at first,” for they “insist the stories are true.” This idea of “truth” seems to be part of the way the podcast takes “the rules of documentary-style podcasting [to] use them to create spooky, cyclical sci-fi—something between Lost and the radio horror plays of the ‘30s and ‘40s but, you know, moonlighting as a documentary.” And as a result, it’s the format of the podcast—not just its documentary styling but the audio nature of podcasting itself—that enhances the horror of its subject matter: “When it’s at its best, The Black Tapes is legitimately creepy, likely more so for its audio format; the big reveal that so often ruins horror movies, where the terrifying monster turns out to be just some shifty stitched-together CGI, never comes.”

This audio format has me thinking about manifestations of horror narratives in both visual and nonvisual forms. Indeed, I’ve been thinking about how it is both visual and nonvisual forms, forms like podcasts and video games, tell scary stories differently. But I’ve also been thinking—what does it even mean to be visual? Is there a difference between the visual and visuality, between what we see and what we imagine? And how do such things relate to ideas of truth and reality?

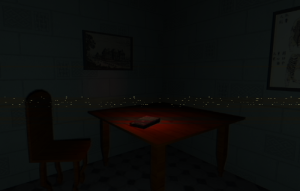

Such questions seem especially relevant when considering Anatomy, for these questions about truth and the visual seem to permeate the game’s exploration of whether or not we can trust what we see in the environment in which we are located. Indeed, Dante Douglas argues that this idea of trust is vital to the way we play the game: “A motif that becomes clear throughout playthroughs is that of trust, or more specifically, trust in architecture. The game taunts you with its familiarity, but bathes everything in darkness. I found myself clinging to walls, running from the dark as a child would, and my heart pounding were I to venture into the pure darkness of the basement or garage.” This taunting familiarity bathed in darkness allows us to question our vision, to question where we are, to see horror where there is simply darkness, to see monsters when nothing is there. The darkness, then, fills us with doubt—doubt regarding whether or not we can trust the house through which we wander or the eyes through which we see. In this way, the house has us questioning its setting (the house) and our bodies (our eyes) at the same time, thereby conflating its architecture with our embodiment—the house as (untrustworthy) body. And this results in what Douglas calls the “subtle horror” of the game:

Such questions seem especially relevant when considering Anatomy, for these questions about truth and the visual seem to permeate the game’s exploration of whether or not we can trust what we see in the environment in which we are located. Indeed, Dante Douglas argues that this idea of trust is vital to the way we play the game: “A motif that becomes clear throughout playthroughs is that of trust, or more specifically, trust in architecture. The game taunts you with its familiarity, but bathes everything in darkness. I found myself clinging to walls, running from the dark as a child would, and my heart pounding were I to venture into the pure darkness of the basement or garage.” This taunting familiarity bathed in darkness allows us to question our vision, to question where we are, to see horror where there is simply darkness, to see monsters when nothing is there. The darkness, then, fills us with doubt—doubt regarding whether or not we can trust the house through which we wander or the eyes through which we see. In this way, the house has us questioning its setting (the house) and our bodies (our eyes) at the same time, thereby conflating its architecture with our embodiment—the house as (untrustworthy) body. And this results in what Douglas calls the “subtle horror” of the game:

The subtle horror is magnificent. I know there is no one else here. That is the most frightening part: there is only me, and the building itself. The fear comes out of the game communicating to me that it is not monsters or intruders that one should be afraid of, but the trust that the building will protect you — or more specifically, what will happen should the building decide not to protect you any longer.

But because the game conflates the house with the body, it also asks us, then, not only to wonder what will happen if the building no longer protects us but also to wonder what would happen if our bodies no longer protect us either. And, as Douglas puts it, “It is a terrifying thing to be afraid of a structure built to keep you safe.”

Like The Black Tapes Podcast, which uses its eponymous black tapes to drive its story forward, so too does Anatomy make use of tapes to drive its narrative forward, albeit tapes of a different sort—that is, cassette tapes. Douglas explains that our gameplay “revolves around a hunt for objects—in this case, tapes. Find a tape, play it in the tape recorder, layer on an ensuing sense of dread, and repeat.” But as we repeat, these “tape recordings, starting as a philosophical comparison of home architecture to the body, become twisted and distorted on subsequent playthroughs.” And as the tapes become twisted and distorted, so too does the house:

The house itself changes architecture, and Horrorshow deftly uses glitched design to her advantage to give the game a sense of unreality. The house, originally an ominous but largely logical space, becomes a structure plagued with grotesqueries: flesh crawling from the walls, windows and doors flashing in futile misplaced-ness, furniture and decorations askew and frozen in air. Each playthrough seems to disturb the house further. The player acts the intruder, poking at the flesh of something much more terrifying than they.

Such grotesque distortions enhance our mistrust of the space of the house by also having us question who (or what) it is that is in control:

As with every other part of the game, it becomes clear that the thing guiding this game is not the player or their actions, but the home itself. It is only after the player completes the ritual of finding the tape, putting it in the tape player, and listening to the entirety that the house decides to unlock another door. It’s a small thing, but the message is clear: You do not call the shots. This house — this monster of a house — is the only thing in control here.

This issue of control seems especially interesting when thinking about the manner in which the game interrogates embodiment, for “[a]t its core, it is a game about relationship to body, fitting for the title. The anatomy of the house, likened often to the anatomy of the human body, is cast as both backdrop and object of horror.” And if what we see in the house is horrific, then perhaps, too, the way we see it (or the way we don’t see it, or the way we think we see it), the way we embody the visuality of horror, is also meant to be horrific.

This issue of control seems especially interesting when thinking about the manner in which the game interrogates embodiment, for “[a]t its core, it is a game about relationship to body, fitting for the title. The anatomy of the house, likened often to the anatomy of the human body, is cast as both backdrop and object of horror.” And if what we see in the house is horrific, then perhaps, too, the way we see it (or the way we don’t see it, or the way we think we see it), the way we embody the visuality of horror, is also meant to be horrific.

So, ultimately, I think that both visual and nonvisual forms allow us, in both intersecting and diverging ways, to interrogate our trust and mistrust in the visual and in our embodiment of what and how it is we see. For, as Reagan asks in the 112th episode of The Black Tapes Podcast, “Do we see only what we want to see? What we expect to see? Or are there some things in this world that we just can’t—and perhaps won’t ever—understand? And if so, is a little bit of mystery in the world such a bad thing?”