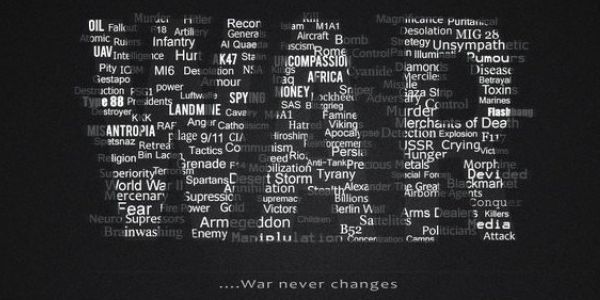

Because I obviously enjoy being sad, depressed, and/or miserable, I’m going to continue this conversation regarding feminism and war in light of 11 bit studio’s most recent game – This War of Mine: The Little Ones. To have a better grasp of what I’m processing through and digging deeper to understand, I began playing CoD: Black Ops III; and the sheer violence, gore, and “natural” representation of what war often is depicted as in contemporary media, quite frankly, traumatized me. I had to pause, and even considered stopping the game – a very different experience than the one I’ve had playing TWoM. In CoD, my character’s body is dismembered by a military robot in Ethiopia, ruthlessly. The screams, blood, and sheer terror in the character’s voice resulted in a realization of what war is: Injury to bodies; violent encounters with “others”; inescapable pain. The game continues on with the body that remained being (re)born, (re)created, from advanced military cybernetic  enhancements. The human has evolved into a well programmed, military weapon that is now nearly indestructible, nearly inhumane. The player continues on, discovering new capabilities, upgrading weapons, advancing in strength, and destroying lives in some place “over there.” So far into my play, there is no discussion of the experience of war outside of this socially instituted conception we have all grown to understand war to be: heroic stories of battles [for freedom]. In her book, War as Experience, Christine Sylvester argues that these social institutions, such as war, heterosexuality, and marriage, are “regimes of truth that emerge over time and dominate alternative ways of living to such a degree that they seem normal and natural, or at least unavoidable.” We are stuck in a perpetual belief that war is inevitable, and yet we hardly understand what war actually is.

enhancements. The human has evolved into a well programmed, military weapon that is now nearly indestructible, nearly inhumane. The player continues on, discovering new capabilities, upgrading weapons, advancing in strength, and destroying lives in some place “over there.” So far into my play, there is no discussion of the experience of war outside of this socially instituted conception we have all grown to understand war to be: heroic stories of battles [for freedom]. In her book, War as Experience, Christine Sylvester argues that these social institutions, such as war, heterosexuality, and marriage, are “regimes of truth that emerge over time and dominate alternative ways of living to such a degree that they seem normal and natural, or at least unavoidable.” We are stuck in a perpetual belief that war is inevitable, and yet we hardly understand what war actually is.

Defining War

In trying to make a clearer distinction between TWoM and other war-like games, I’ve grown to appreciate Sylvester’s definition of war over the traditionally simplified version that it is nothing more than armed conflict between nations or states; “war is a politics of injury: everything about war aims to injure people and/or their social surroundings as a way of resolving disagreement or in some cases, encouraging disagreement if it is profitable to do so” (Sylvester). Rather than thinking that injury [to bodies] is a consequence of war, consider instead that injury is the very content of war. I mention bodies because it is bodies that experience war, both emotionally/psychologically and physically, in differentiated and meditated ways. When considering the role of feminism in war, we’re presented with a conundrum, though. War is often not “owned” by feminists. The angle from which to investigate such games, then, becomes less defined, less sure. Yet, any institution dealing with, or affecting, embodiment of “women” and “men” deserves to to be investigated.

in differentiated and meditated ways. When considering the role of feminism in war, we’re presented with a conundrum, though. War is often not “owned” by feminists. The angle from which to investigate such games, then, becomes less defined, less sure. Yet, any institution dealing with, or affecting, embodiment of “women” and “men” deserves to to be investigated.

Bodies, men and women, in CoD are for training, shooting, and dying and are “owned” by another entity. Of course, I accept that I’m generalizing, and perhaps I’ve not gotten to the greater narrative the extends beyond an “us and them” politicized battle, often depicted in a masculine light. However, the very title of This War of Mine is feminist. There’s an identifying with experience, a bodily experience in war; and the content is [injury of] self, not other. The very definition of the pronoun mine refers to possession: that which belongs to me. It’s a matter of taking ownership and controlling the narrative rather than following a linear path of mass destruction (unless you so choose). In TWoM, you aren’t handed a weapon and taken through a tutorial. You are quite literally put in an abandoned building and your first task is to scavenge that building for materials you can use to build your defenses against the conditions you’ve been subjected to. In comparing the experiences of men and women in TWoM, neither is made to be better or stronger and strict gender binaries don’t exist. Women tend to be able to carry more, scavenge and negotiate better, and generally keep “level-headed.” Arica, for example, is a younger woman, about early twenties, from the hood, who has had a relatively hard life already, making her experiences with this war an extension of the trauma she’s already an endured. Palve, a former solider, reveals his experiences with the war in a negative light, revolting against the very concept of even having been a solider, choosing to desert that war for his own. Not only are aspects of gender present, but generational constructs are as well. Grandparents, parents, and children are all bodies experiencing war in varied ways, challenging the normative perceptions of what war is, what war means, what war does, and who survives war. What’s more, the traditional “heroes” of war, the snipers, are identified as rapists, thieves, and overall abusers of power who manipulate citizens daily. Engaging with and challenging these cultural and social constructs, makes TWoM an inherently feminist game, and brings to light [in the Western world] the lived experiences of bodies “over there”. As Sylvester notes, “Some war deaths are counted and grieved and many others are ignored — because deaths of everyday people in wars ‘over there’ are collateral rather than important damage for the counters to tally.” Of course, another distinction to make is that TWoM, as previously mentioned, is based on the actual Bosnian War unlike CoD, an imaginative game feeding a false representation of war.

Considering this developing discussion that I’m having, most often, with myself, I would like to expand that and see what others think about these ideas.