This summer, I’m in a class focused on women in games, and it’s exactly what you’d expect: one step forward, 97,000 steps back at every turn. The success stories—of games, characters, girl gaming clubs, industry professionals, more—are both wonderful and terrible. Wonderful because we’re starved for them; terrible because those stories are so often faint stars in a darkened sky.

We’ve been playing a lot of games. It’s a long class, and it meets every day, so there’s plenty of time to talk and play and critique, something that might not work as well with a group less engaged, but for us, it’s been wonderful so far. Imagine this: a room full of women and allies, varying in ages, skill levels, backgrounds, and interests, all in the same place for different reasons. Some want to work in the industry; some want to be teachers; some just thought the course sounded interesting. We are undergrads and grad students, and the grad students are from a smattering of fields. Some of us study games as a focus; some do not. Some of the people in the room haven’t played a game in years. Some really never played at all.

Everyone’s here from a different place, for different reasons, and every day, we’re playing, trading controllers, talking each other through sections, laughing at the silly moments, groaning over bad dialogue, shouting as one at death.

This kind of cooperative critical play may be what I love most about games studies, because it’s part of what I love most of playing with my friends and my partner. Tackling the single-player together opens space to talk and think about things we might not notice on our own. And, let’s be fair: the day we played Rock Band 4, there wasn’t a lot of critical play happening; everyone was focused on simply playing, or singing along. But when it’s American McGee’s Alice or the Tomb Raider reboot, the world opens up. There’s someone on hand to spot every detail, to argue for or against every design decision. Group critical play offers everyone a new perspective, even if you never touch the controller.

I don’t often talk about the Tomb Raider reboot; it makes me somewhat irrationally angry, in the way of so many games that are rich with story and character potential, with shining moments, but that ultimately fall flat for me in a number of ways (see: all my feelings about The Last of Us), but we had a good, lengthy conversation about the game as we played last week, from Lara’s vulnerability to men, the elements, and more (as well as her somewhat empty moments of emotional vulnerability), through the fact that it’s a man who guides her, and on, and on. While there’s definitely something to be said for Lara picking up and carrying on after a series of men fail her, thwart her, help her, and more, the fact that she’s really only following men is a little troublesome to me, as is the fact that the growth doesn’t always ring true – sometimes the game gets in the way of itself, a common problem, I think, with games in general. We talked too about her physical development, the design of her body, the voyeuristic camera shots into her tank top, really just everything that could come up about Tomb Raider in a short but robust discussion, even down to controls and animations (and of course, the infamous hair; oh, that hair). But it was what came after class that really got me thinking about stories and characters, and ways that we can create games that feel more authentic, more organic. My friend Tony asked, as we were walking across campus, what I thought could be done to improve stories like Lara Croft’s. There were obvious things we discussed, more difficult things like her physical form developing as she develops greater skills (at least with a shift in animations, maybe), and considerations like female leaders and guides. We spoke too about her emotional development, tweaking it, giving the events more resonance, but that’s an issue with so many games that it’s hardly unique here.

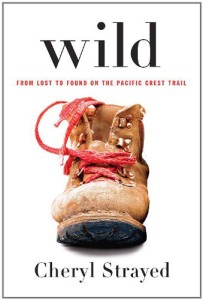

But the training, he said. How can you really develop her? Is it as easy as just swapping out her male mentors for women? And I thought then of Cheryl Strayed’s memoir Wild, a book Tony’d never read, but as I explained the plot, I kept thinking more and more about what a fantastic model it would be for a physical coming-of-age story like Lara’s. When I got home, I paged through my copy, re-reading sections, thinking about the very real world Strayed had navigated in her 1,000-mile hike on the Pacific Coast trail. That, too, was a very male-dominated space; while she encounters other female hikers, they are not alone like she is, nor going as far, nor as numerous as the men. It’s the men, too, who help her when she begins on the trail, offering advice and assistance. She feels that weight throughout, the weight of having to fit into a male-dominated space, to be “one of the guys,” to prove that she can lift her massive pack, even when, at the beginning, she can barely get it on, much less go very far with it. But over the course of the hike, she changes. She shifts from the young woman who foolishly bought things she didn’t need, to prepare for a journey she didn’t understand, into a woman who loses her boots far from civilization and manages to fashion replacements out of duct tape until she can make it to the next stop. She changes from someone merely sad, broken, ambitious but not fully able, into someone capable and strong.

But the training, he said. How can you really develop her? Is it as easy as just swapping out her male mentors for women? And I thought then of Cheryl Strayed’s memoir Wild, a book Tony’d never read, but as I explained the plot, I kept thinking more and more about what a fantastic model it would be for a physical coming-of-age story like Lara’s. When I got home, I paged through my copy, re-reading sections, thinking about the very real world Strayed had navigated in her 1,000-mile hike on the Pacific Coast trail. That, too, was a very male-dominated space; while she encounters other female hikers, they are not alone like she is, nor going as far, nor as numerous as the men. It’s the men, too, who help her when she begins on the trail, offering advice and assistance. She feels that weight throughout, the weight of having to fit into a male-dominated space, to be “one of the guys,” to prove that she can lift her massive pack, even when, at the beginning, she can barely get it on, much less go very far with it. But over the course of the hike, she changes. She shifts from the young woman who foolishly bought things she didn’t need, to prepare for a journey she didn’t understand, into a woman who loses her boots far from civilization and manages to fashion replacements out of duct tape until she can make it to the next stop. She changes from someone merely sad, broken, ambitious but not fully able, into someone capable and strong.

Along the way, she meets and is aided by more than just men, and all these people contribute to her success and development. She hears their stories, travels with them, learns from them, is fed and aided by them, but even with help, she makes it through the worst parts of the trail alone, and by the end, it’s in her. It is her. She has become someone different. More, that difference shines in everything she does, in every action; it’s not just something that happens when it’s convenient, and everything has an impact that shows in Strayed as she goes on and on. It’s still there now when she writes.

Lara looks much the same in the sequel, Rise of the Tomb Raider, as she did in Tomb Raider. Of course, this saves money, but when she attempts long jumps forward, it’s still with the same wild, flailing motion. She’s more capable now, sure; she’s better, faster, stronger. But I’m greedy and I want to see it. I want to see it in her. I want organic change. I want a Lara who isn’t just affected in the moment, but one who reflects growth. This is supposed to be the character-defining journey, so what’s defined? What’s developed? How does this story shape her into the Lara who says later, with wonder, “I can make the right difference” – has she become that Lara?

This isn’t unique to Lara Croft; Nathan Drake, too, has got to be the most incompetent-seeming adventurer in all the land, flailing and nearly failing at all turns. Sure, he can fight, and he can kill, but his near-misses provide the opportunity for his little one-liners and complaints, and all that makes him successful is the player’s skill. The player’s effort. Maybe there’s something to that, but you’d think over the timeline, maybe Drake could have refined some of his skills a bit. Some people seem to think this constant oops mentality is part of his charm; I think it’s a symptom of games, which feel the need to find a way to value player skill and not always make the player-character an expert, except when they need to be an expert.

I bring up Wild because it’s a story about not only finding, but growing into strength. About becoming. Lara’s arc is similar, or should be, but it never feels similar. She’s only breaking into a world of men (at least until the second game), though there’s no reason for so few women in those roles of authority and power beyond the fact that it was designed that way. While it does help reinforce Lara’s fight to be self-defined, it feels calculated. Designed. Just as Lara’s struggles to kill and her emotional developments are washed away when she immediately does it again and again and again. Her first kill is a moment designed to feel emotional, but then immediately undermined.

And let’s not forget: this is the game that begins with Lara’s motivational monologue about finding strength within yourself… just before she’s saved from drowning by a man. Of course, I know she hasn’t found said strength at that time, but if that isn’t impeccable irony, I don’t know what is.

Maybe that’s just games. Maybe games have to be a bit simplified. But I’d like to think not. I’d like to think there are ways to be better.

Rhianna Pratchett herself, writer for the new Tomb Raider, has argued for writers to have larger roles, to be brought in sooner, for story to be twined through games from the beginning, and I think she’s right: stories in games seldom have time to breathe. There’s always the next thing. Even after an emotional moment – Lara Croft’s first experience killing a man, the mercy-killing in my go-to, State of Decay, Aerith’s death in Final Fantasy VII – physically, everyone moves on. Maybe the scenes themselves are intense, revealing, inspiring, whatever, but after? We don’t see our heroes stop and compose themselves, eyes squeezed shut. We don’t see them wipe away tears, or vomit, or talk themselves back into focus. Their postures don’t change. They don’t square their shoulders and decide to go on, unless it’s a cutscene designed to do something like that.

But how can games do this, really? After all, if women are simply too difficult to code because of all their emotions or whatever, we can’t expect reactions. Sarcasm aside, every gesture, every movement, every moment represents a team of people working and creating and refining. There’s just no room for those little things in most games, and no money to spare, but the dissonance created by that lack undermines even the most well-crafted games.

Until Dawn comes closer than many games I’ve played to matching all that up, but considering it’s essentially a movie, that makes sense. It is, however, a movie broken up by sequences that require multiple button presses to open a cabinet, so gain one thing, lose another.

How then can we begin to critique games? How have we been? Different reviewers hold different things sacred; different cultural critiques explore different aspects, but as criticism goes, we’re always comparing, even when we’re not actively talking about comparisons. We’re thinking about story in terms of other stories – books, films, television – but a game is none of those things. We’re thinking about games in terms of other games, but they’re not the same, either. I’m thinking about the upcoming Dishonored sequel, probably one of my most anticipated games right now, and when we play it, when we review it, when we think about it, it will be impossible to untangle from the first game. Except… it’s not the same game. It’s not even a similar game, beyond the major concepts: stealth, action, chaos, choice. Here, you can choose whom to be, and the world from Emily’s perspective should not be the world from Corvo’s perspective. Neither should be the perspective of the first game. Things are different. The world has moved on.

How then can we begin to critique games? How have we been? Different reviewers hold different things sacred; different cultural critiques explore different aspects, but as criticism goes, we’re always comparing, even when we’re not actively talking about comparisons. We’re thinking about story in terms of other stories – books, films, television – but a game is none of those things. We’re thinking about games in terms of other games, but they’re not the same, either. I’m thinking about the upcoming Dishonored sequel, probably one of my most anticipated games right now, and when we play it, when we review it, when we think about it, it will be impossible to untangle from the first game. Except… it’s not the same game. It’s not even a similar game, beyond the major concepts: stealth, action, chaos, choice. Here, you can choose whom to be, and the world from Emily’s perspective should not be the world from Corvo’s perspective. Neither should be the perspective of the first game. Things are different. The world has moved on.

But comparison is natural. Even if we try to avoid it, it will still be there, lurking. We measure, and other games, other stories, are our scales. But each game is its own blend, harmonious or not, of story, movement, sound, visual, system. Shifts in teams create shifts in games. Even what’s similar may not be the same. So should we work to take each game on its own, discovering anew the peculiar combination of factors that come together for this experience? We can’t, not always, certainly not with sequels or franchises; each is informed by the other. Sequel-Lara Croft should be stronger, perhaps with more developed arms, more controlled jumps, a more practical hairstyle. Organic growth. But that’s part of the coming-together of factors, or should be, maybe.

Games are hard. This is what I come back to. Games are hard to make, to read, to play, to consider.

In class, we’ve talked a bit about backgrounds, and art, the look of games. We loved Yoshi’s Wooly World; we hated the clunky visuals of ill-made “girl games.” Alice was fascinating, creepy; we were both easily lost and easily re-oriented when we stopped to pay attention. We talked at length about the world of Tomb Raider, the lush visuals, Lara’s hair (like she has a personal breeze), the leaves, the view from a rock, the depth and care of it all, and we wondered if it was necessary.

Is that where the money goes? Into the light on a fluttering leaf? Into animating Lara’s hair? Whitman’s hair, despite a few drawn-on stray individual hairs (for realism) is a solid mass. In the wind, we see Lara’s hair moving, but Sam’s is still. Dissonance. But imagine the cost to animate all of it. Everyone.

In Tomb Raider, it’s as though Lara alone exists in full relief, in a spotlight that gives her air and life and breath; everyone else is an imprint, faded. This is us: we are alive, and they are simply images, extras, set dressing, part of the story. It makes sense, maybe, considered from that angle. Maybe.

What I want, I think, from a game, is the impossible. I want Beyond-level organic choices and opportunities, Shenmue-style realism and ability to interact with the environment, I want story that resonates, I want smooth controls that don’t strain my hands (or I want to be able to adjust them, at least), I want organic growth and change. I don’t care about individually moving leaves, breeze, or famous actors – especially famous actors. Until Dawn’s lesser-knowns were as good as Hayden Panettiere. Maybe better. And I’m sure they put less of a dent in the budget, but that’s just a guess. I love Willem Dafoe, but I don’t need him in a game. The world is full of actors. I can send along some names.

But it’s hard. Games are costly, and money must be made. It’s give and take, and not always the best sense driving every decision. Eurogamer’s recent longform story of Lionhead’s journey is revealing not only because sure, we all want details, but my goodness, these details. Teams getting ahead of one another. Art languishing while game catches up. HR crises. Marketing teams looking at broad strokes and not finer details (and never, of course, potential). I’m not the only one who wants something bigger, more alive, but there are so many moving parts. There is so much to consider.

But it’s hard. Games are costly, and money must be made. It’s give and take, and not always the best sense driving every decision. Eurogamer’s recent longform story of Lionhead’s journey is revealing not only because sure, we all want details, but my goodness, these details. Teams getting ahead of one another. Art languishing while game catches up. HR crises. Marketing teams looking at broad strokes and not finer details (and never, of course, potential). I’m not the only one who wants something bigger, more alive, but there are so many moving parts. There is so much to consider.

But imagine again that room, full of women and others, all playing, 3-4-5 different games going on at once, and whether the games are “good” or not, we’re all laughing. Maybe we’re groaning over dialogue or death or graphics, but we’re laughing, because we’re playing games, and even imperfect games are fun. They bring something to our lives. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t want more, or strive for it, but it’s important, too, to remember where we are and what we have.

It’s important, too, to remember that in that room, there’s nothing more than a little good-natured ribbing. There are no slurs. No rolled eyes and controllers wrenched from hands. We are moving as teams, encouraging, and even if someone isn’t the best in that moment, well, it’s fine. There’s still something to be gained, just as with those imperfect games.

The wider industry is a little broken; gaming communities often more so. But there is, after all, a crack in everything. And we’ve got the light. We’ll follow it and see where it goes.