I’ve been catching up on a lot of reading this summer, and much of what I’ve been reading engages with the complexities of family structures and kinship ties. From Dorothy Allison’s Bastard out of Carolina to Suzan-Lori Parks’s Getting Mother’s Body, from Ruth Ozeki’s My Year of Meats to Toni Morrison’s Beloved, at the heart of such engagements with family structures is the representation of parenting roles, especially that of motherhood. And one branch of literature that seems especially concerned with the role of the mother is that of feminist science fiction, a genre that works to critique the hegemonic patriarchal structures in which we are embedded while (at the same time) imagining a future that transgresses the boundaries of such structures. The patriarchal configuration of motherhood is one such structure that feminist science fiction seeks to reimagine and dismantle.

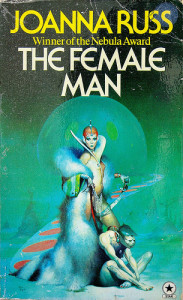

Works like Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, Joanna Russ’s The Female Man, and Octavia Butler’s Dawn, for instance, afford us a particularly generative lens through which to problematize patriarchal modes of parenting and through which to imagine ways to challenge and disrupt such structures by constructing other possible structures of kinship, family, and parenting. And in the course of my thinking about such disruptive representations of motherhood and parenting, I’ve come to wonder how these feminist reimaginings converse with the kinds of representations we’ve been seeing (or, really, not seeing) in video games.

Works like Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, Joanna Russ’s The Female Man, and Octavia Butler’s Dawn, for instance, afford us a particularly generative lens through which to problematize patriarchal modes of parenting and through which to imagine ways to challenge and disrupt such structures by constructing other possible structures of kinship, family, and parenting. And in the course of my thinking about such disruptive representations of motherhood and parenting, I’ve come to wonder how these feminist reimaginings converse with the kinds of representations we’ve been seeing (or, really, not seeing) in video games.

To be sure, feminist science fiction’s reimaginings of parenting roles seem to be a continuation of the kinds of discussions that have been occurring among feminist theorists. Adrienne Rich, of course, interrogates patriarchal family structures in Of Woman Born, and Andrea O’Reilly extends Rich’s interrogation in “Mothering against Motherhood and the Possibility of Empowered Maternity for Mothers and Their Children,” in which O’Reilly argues that motherhood must be transformed into a site of power in order for nonpatriarchal experiences of mothering to occur. As such, O’Reilly maintains that women must “mother against motherhood” in order to bring about empowered, antisexist conceptions of mothering. While O’Reilly’s assertions for mothering against motherhood place the burden for change primarily on mothers (those who are oppressed by the very structures she critiques), and while her assertions also seem to emphasize more individualistic notions of empowerment rather than conceiving of more collective ideas for the dismantling of patriarchal configurations of family and parenting, her argument in favor of changing the conditions of motherhood allows us to turn toward conceiving of ways we might embark on such change and allows us to begin the process of (re)imagining feminist models of motherhood instead.

To be sure, feminist fiction often seeks to embark on such processes of reimagining through the representation of feminist transformation, and the genre of feminist science fiction in particular seems especially effective at imagining such possibilities for transformation. Feminist science fiction specifically conceives of such transformations through a lens that seeks to imagine a feminist future while, at the same time, recognizing the obstacles and challenges we might face in the path to such a future. In other words, many works of feminist science fiction work to conceive of different ways of experiencing gender in an effort to critique intersections of race and gender and the manner in which the oppression that occurs at such an intersection might be transgressed and dismantled. And one specific institution of oppression that such works often interrogate is that of motherhood in order to conceive of a reimagined feminist model of mothering.

To be sure, feminist fiction often seeks to embark on such processes of reimagining through the representation of feminist transformation, and the genre of feminist science fiction in particular seems especially effective at imagining such possibilities for transformation. Feminist science fiction specifically conceives of such transformations through a lens that seeks to imagine a feminist future while, at the same time, recognizing the obstacles and challenges we might face in the path to such a future. In other words, many works of feminist science fiction work to conceive of different ways of experiencing gender in an effort to critique intersections of race and gender and the manner in which the oppression that occurs at such an intersection might be transgressed and dismantled. And one specific institution of oppression that such works often interrogate is that of motherhood in order to conceive of a reimagined feminist model of mothering.

Whether it’s Le Guin’s representation of an ambisexual, androgynous society in which gender identity and parenting roles are not fixed but, rather, fluid in The Left Hand of Darkness; or Russ’s conception of a Whileaway, a utopian society of the future in which motherhood is constructed as a period of leisure; or Butler’s depiction of Lilith, a black woman who becomes mother to a new human-alien race—what all such representations reveal are the varied ways that we might critique patriarchal configurations of parenting while imagining alternative configurations that do not privilege the power of the father.

But, so far, it seems we haven’t seen such alternative configurations in video games. Instead, as Colin Campbell puts it, “Game development teams — very often led by middle aged men — are happy to churn out fictional models of brooding, paternal excellence. But they take a very different approach to depicting motherhood.” This different approach, Campbell continues, results in the treatment of “moms as background narrative props for protagonists, very often dead or absent. Sometimes, older women with children are presented as anti-moms, whose quest for power concludes with sentiments of regret generally absent from games in which male villains are vanquished. Those women who are portrayed as positive mother figures are often not actual mothers at all.” And while mothers continue to be rendered invisible in video games, fathers continue to be constructed as heroes, for Campbell points out that the “recent E3 games convention showed the likes of Kratos, Marcus Fenix and Corvo joining Booker DeWitt, Joel and Ethan Mars as tender-but-tough paragons of fatherhood.” And this all causes Campbell to ask, “So where are the heroic moms?”

One answer to that question might be that they exist within the pages of feminist science fiction. And it would be nice to see such heroes exist in video games too. Because, as Joanna Russ puts it in The Female Man, “I didn’t and don’t want to be a ‘feminine’ version or a diluted version or a special version or a subsidiary version or an ancillary version, or an adapted version of the heroes I admire. I want to be the heroes themselves.”

One answer to that question might be that they exist within the pages of feminist science fiction. And it would be nice to see such heroes exist in video games too. Because, as Joanna Russ puts it in The Female Man, “I didn’t and don’t want to be a ‘feminine’ version or a diluted version or a special version or a subsidiary version or an ancillary version, or an adapted version of the heroes I admire. I want to be the heroes themselves.”