In December of 2013, I’d just started dating my partner. I was also working a dead-end job in an attempt to lessen the debt I was digging myself into by going to college. That job sent me to Terre Haute for a good portion of my winter break, where I worked twelve hour days (including on Christmas) and relied heavily on my partner’s Skype conversations to stay sane.

So when I finally got time off, my partner came and picked me up. I went to stay at his house, where he set me with a game on his computer.

“To keep you entertained while I visit my mom,” he said. “It’s fun. All you do is burn things.” Seemed simple enough to me.

When he came back a few hours later, I pelted him in the face with all the pillows from his bed.

“What?!” he said, with a smile that stated he knew exactly why he was getting hit with pillows.

“You didn’t say it was going to be sad!”

—

The game my partner put in front of me that day was the Tomorrow Corporation’s Little Inferno. Released originally in 2012 for the Wii U, it expanded to PC and mobile markets in 2013, when I finally played it. Slated as a sandbox puzzle game, you make combos in your “Little Inferno Entertainment Fireplace” and earn money. So yes, on a very basic level, the game is simple. As my partner said, all you do is burn things.

It’s very fun and surprisingly cathartic. And kind of dark, actually. Macabre even. Some of the stuff screams when you burn it. It’s kind of creepy to watch screaming marshmallows, to be honest.

On a slightly deeper level, it is kind of obvious that this game is also a satire of sandbox games in general. As the Little Inferno Wiki says “The game was designed as a satire of similarly themed video games in which the player dedicates long amounts of time to performing tasks considered to be unrewarding.” That I can agree with. I find the tongue in cheek humor about the “pay to win” (shown in the game as buying from the catalogue to advance through the game), nods to mobile games and Facebook-style waiting. The game also makes you think of the age old question of why do people spend money on those Yule Log simulators.

Wired ran an article in February 2013 called “Little Inferno Mocks the Players Who Love It Most” . In it, writer Ryan Rigney makes nods to the game’s satire, such as with the “Casual Gaming System” and the “Gaming Tablet,” that all make commentary on the state of mobile and so-called casual gaming styles. What I don’t agree with in this article is Rigney’s insistence that Little Inferno is making fun of casual gaming.

“Whenever I ordered a big new shipment of things to burn, I often found myself staring at my inferno, just waiting for the imaginary packages to arrive. I was accomplishing nothing. I could’ve been reading a book, or speaking to someone who matters to me, or even playing a different videogame that could challenge my mind and force me to think in new ways.

Instead, I was gaping at an iPad screen, watching a timer tick down, effectively no longer connected to the world around me, with minutes of my life ticking away.”

Rigney states that this is part of the game’s “genius”, as it is still fun despite being simple, but I wonder why he (and the gaming community in general) have such a problem with that. I mean, because really, what do you actually accomplish in a first person shooter?

Also, I kind of think that Rigney missed the point in his article. Because, sure, I got that satire on casual gaming (and gaming in general) from Little Inferno. But I feel like that was just the surface argument presented by this game.

Remember before? I said it was sad. But maybe melancholy is a better word.

—

There’s an actual plot to Little Inferno. It’s told mostly through letters sent to the player character, an unnamed person, from NPCs. There aren’t many characters in the game. Other than the player character, there are four NPCs. Three send you letters and the fourth comes to you in a different way.

Miss Nancy sends the letters about the fireplace where the game play takes place, Sugar Plumps sends letters of friendship and hints on how to progress, and Weather Man sends worrisome (to me) reports of how the outside world is.

From left to right:

The Weather Man, Sugar Plumps, and Miss Nancy

See, you learn very quickly that it’s been snowing for a very long time and no one is sure when it’s going to stop. The days are getting colder and forcing people inside. Everyone is clustered around their fireplaces, potentially burning everything they have (and more) to stay warm.

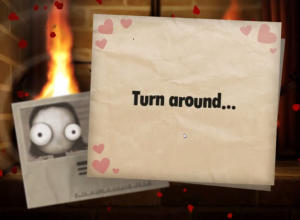

As your friend Sugar Plumps writes, at one point, “I think I’m trapped in here. And so are you.” She later asks the player to turn around. In the real world, you can. But the player character can’t (they try though).

And the Weather Man, your only viewer of the actual outside world, keeps reporting clouds rolling in and snow keeps falling and smoke constantly rolls from people’s chimneys. In fact, it is starting to seem like the smoke may become more of a problem than the snow.

The cycle is not lost on me, as I am sure the situation keeps getting worse as more people keep burning things to stay alive. If you don’t, you’ll freeze, but if you do, you’ll make the world colder. Sort of a simplified global warming situation.

This game exists in a strange isolation. The player character is talked to by, but has little connection with the outside world. I found myself, despite the fun I was having setting literally everything on fire, waiting for the next letter from Sugar Plumps or the Weather Man.

In my story above, my partner got pillows to the face because the loneliness was really setting in,

especially after Sugar Plumps stopped writing.

That’s about when I realized, or at least assumed, there was more to this game than met the eye. It’s not often games make me feel lonely. In fact, I typically play games to keep me from other people.

But something about this game made me think about the specific isolation of it. Not just the isolation created by games, but something more.

Chalk it up in the Jynx Thinks Too Deeply About Things if you want, but I began thinking about how this game reflects the problems with just focusing on yourself. Not expanding your worldview, or seeing what impact you have on the area around you. Having the privilege to ignore the change you have to a space. Or just assuming that the change that occurs isn’t your problem at all.

—

When talking about this game–it comes up randomly in my partner and my conversations–my partner brought up something he calls the “bird feed effect.” Basically, it summed up as this: when you throw birdseed on the ground for a flock of pigeons, obviously the pigeons are going to try to get as much of the food as possible for themselves. But the pigeons look up every so often, to scout out danger. Pigeons that look up ultimately serve as warning for the other pigeons that are eating, effectively keeping the whole flock safer.

Does this make the birds selfless? After all they are losing food to keep their eyes up. Or is it an instinctual habit learned to keep others safe? Or are they just curious about where the food came from? (Truly though, are birds capable of that level of thought?)

So what happens when no pigeons look up?

Well, there are a lot less pigeons.

Little Inferno, to me, is about a world where no one looks up. The world is slowly freezing over, but that’s okay. Stay inside, burn your memories, and I’m sure everything will be alright in the end.

But that’s the problem. It won’t be alright. And little hints, from Sugar Plumps and the Weather Man and the Little Inferno Instructional Video hint towards that.

So the game becomes more than burning slightly cute but creepy things in a fireplace. It becomes a game about trying to figure out how you go from looking down to looking around. To looking up and learning something.

—

If nothing else can be said about Little Inferno, it’s a surprisingly self-aware game. I also think it has various layers of commentary, depending on how deep you are willing to look.

It’s the first time in a long time that a game has made me feel completely and utterly alone.

However, I will agree with Rigney, as he said Little Inferno ends on a positive note. Truly, I think it does. Certainly the game takes the player on a journey of sorts. Even if they weren’t aware they were traveling in the first place.

Ultimately, too, the game is about having fun. Casual or not, there’s something quite enjoyable about burning stuff and learning about humanity in the process.

After all, someone has to be the lookout pigeon.

Until that point, however, I’ll be here. “Reporting from the weather balloon, over the smokestacks, over the city.”