Last month, I wrote about the ways feminist science fiction reimagines motherhood and the ways this reimagining of maternal power highlights the limitations in video games’ (often fraught) depictions of motherhood. Lately, after watching Stranger Things, I’ve been thinking particularly about articulations of single motherhood, how it is single mothers have come to be represented, and how such representations are especially articulated in video games.

Last month, I wrote about the ways feminist science fiction reimagines motherhood and the ways this reimagining of maternal power highlights the limitations in video games’ (often fraught) depictions of motherhood. Lately, after watching Stranger Things, I’ve been thinking particularly about articulations of single motherhood, how it is single mothers have come to be represented, and how such representations are especially articulated in video games.

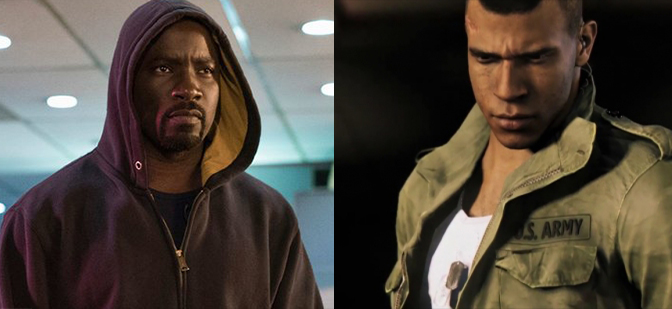

One game that I’ve been playing recently and that comes to mind due to its representation of single motherhood is The Park, which is, as Lauren Orsini puts it, “the latest horror game from Funcom. It’s a two-hour immersive experience in which you play as Lorraine, a woman searching for her child, Callum, in the creepy abandoned Atlantic Island Park…You simply explore and observe your environment until you come to one nightmarish conclusion: you cannot trust your own mind.”

Indeed, we come to this conclusion because of the manner in which Lorraine’s characterization unfolds through the game: “As the game progresses, Lorraine morphs from your typical blue-collar single mom into an unstable mental patient who hallucinates demonic chipmunks and evil clowns and, just maybe, might be responsible for Callum’s disappearance.” Lorraine’s mental health situation is revealed through the fact that she “is shown in no uncertain terms to have anxiety and depression…She is seen to take a ‘Zolift’ prescription, an obvious riff on Zoloft, a common anxiety and depression medication.” And what happens as a result of this characterization and the fact that Lorraine’s mental health is connected to Callum’s disappearance is the fact that both single motherhood and mental illness become demonized and villified, which is especially apparent in one scene that Orsini describes:

Indeed, we come to this conclusion because of the manner in which Lorraine’s characterization unfolds through the game: “As the game progresses, Lorraine morphs from your typical blue-collar single mom into an unstable mental patient who hallucinates demonic chipmunks and evil clowns and, just maybe, might be responsible for Callum’s disappearance.” Lorraine’s mental health situation is revealed through the fact that she “is shown in no uncertain terms to have anxiety and depression…She is seen to take a ‘Zolift’ prescription, an obvious riff on Zoloft, a common anxiety and depression medication.” And what happens as a result of this characterization and the fact that Lorraine’s mental health is connected to Callum’s disappearance is the fact that both single motherhood and mental illness become demonized and villified, which is especially apparent in one scene that Orsini describes:

At one unreal point in the game, you (as Lorraine) are walking in circles around your own apartment, each turn becoming more horrific than the last. In the beginning, you observe your grocery list on the kitchen table—“milk, eggs, Zolift prescription.” Later, the same shopping memo reads, “Zolift prescription, Zolift prescription, Zolift prescription” and is—I kid you not—splattered with blood. A doctor’s note on your desk diagnoses you with anxiety and depression, though the wording later changes to identify you as “batshit f*cking insane.” At one point, after taking your Zolift pills, you are transported to a nightmare world with the Boogeyman standing right in front of you.

As a result, Orsini concludes, “The Park indicates that mental illness is one of the scariest things its writers can imagine.” But more than this, the game also indicates that a single mother is also one of the scariest and most dangerous things its writers can imagine because of the fact that mental illness is specifically situated within Lorraine’s (single) maternal body.

As a result, Orsini concludes, “The Park indicates that mental illness is one of the scariest things its writers can imagine.” But more than this, the game also indicates that a single mother is also one of the scariest and most dangerous things its writers can imagine because of the fact that mental illness is specifically situated within Lorraine’s (single) maternal body.

While playing The Park and thinking about its representations of the intersection of mental health and single motherhood, I’ve also been rewatching Stranger Things and thinking about how Winona Ryder’s character Joyce Byers converses with this intersection and the way it impacts how single moms are represented. Because Joyce’s story—at least, at first—seems to parallel Lorraine’s. She, too, is a single mom. She, too, experiences the trauma of her son Will going missing. She, too, seems to be stigmatized by her community as being mentally unstable. And there seems to be a lot of conversation about the implications of these characterizations of Joyce’s motherhood. Genevieve Valentine, for one, argues that Joyce’s “characterization seems claustrophobic” and also argues that Joyce’s motherhood and singular determination to find her son only makes sense “from the perspective of the young-man nostalgia engine,” a perspective that stems from the idea that “[w]hen you’re a kid, Mom exists only as pertains to you.”

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd, however, sees Joyce’s determination not as a characterization based on “young-man nostalgia” (as Valentine puts it) but rather as one that reveals Joyce to be “working with the rigid focus of someone who would do anything to ensure the safety of her son.” Thus, Shepherd frames Joyce’s motherhood not as a representation that perpetrates the problems of nostalgic motherhood but as one that attempts to reinvent and reframe maternal power: “Running parallel to the primary kid-buddy-movie rubric is an important story about the role of the mother in these types of classic films of the 1980s; with eight hours to tell the story, Ryder’s character is given a much more prominent role than past moms.” But more than this, Joyce’s role in Stranger Things “actually puts into contrast how ‘80s movie moms of this genre…were often written into stories as plot advancers or devices, not necessarily fully fleshed out characters but stand-ins for the true heroes, which were usually boys or men.” However, Joyce, Shepherd argues, is more fully fleshed out than the genre’s past moms:

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd, however, sees Joyce’s determination not as a characterization based on “young-man nostalgia” (as Valentine puts it) but rather as one that reveals Joyce to be “working with the rigid focus of someone who would do anything to ensure the safety of her son.” Thus, Shepherd frames Joyce’s motherhood not as a representation that perpetrates the problems of nostalgic motherhood but as one that attempts to reinvent and reframe maternal power: “Running parallel to the primary kid-buddy-movie rubric is an important story about the role of the mother in these types of classic films of the 1980s; with eight hours to tell the story, Ryder’s character is given a much more prominent role than past moms.” But more than this, Joyce’s role in Stranger Things “actually puts into contrast how ‘80s movie moms of this genre…were often written into stories as plot advancers or devices, not necessarily fully fleshed out characters but stand-ins for the true heroes, which were usually boys or men.” However, Joyce, Shepherd argues, is more fully fleshed out than the genre’s past moms:

As Joyce, Ryder plays up her character’s plight at the precipice of possibly losing her mind with grief at her son’s disappearance. She shrieks and trembles, admits she knows her story—that she can communicate with Will through a series of Christmas lights she’s strung up in her house—sounds crazy. But she’s also reflecting an element of unhinged care that you can surmise any mom might express if her child vanished.

And for Shepherd, these things do not make Joyce feel claustrophobic or nostalgic, as Valentine puts it, but make “Ryder’s character relatable…which helps redeem the freneticism of ‘80s mom characters before her; the primality with which she plays Joyce is an imperative, a survival instinct, and one that, in the end, works.”

So it seems to me that what we are dealing with in The Park and Stranger Things are parallel but differing constructions of single motherhood. Both are oriented toward telling the stories of single mothers searching for their missing sons and enduring the horrors and trauma that result from their sons’ disappearances. But while Stranger Things might work to recast single motherhood as a site of maternal power (to varying degrees of success, depending on what side of the Valentine/Shepherd argument you are), The Park perpetrates the idea of single motherhood as a site of danger, monstrosity, instability, and abnormality. And at the heart of such characterizations is the idea of credibility—for, we are asked to doubt Lorraine’s credibility, stability, and, ultimately, ability to mother due to her construction as mentally unstable, while, on the other hand, we are asked to believe Joyce, to see her not as a dangerously unstable mother but as one who is determined, as one who will face any monster to save her son. Thus, it seems to me that the conversation occurring between The Park and Stranger Things, between Lorraine and Joyce, begins to complicate our understanding of how maternal power can either be reimagined or stifled through representations of single mothers.

So it seems to me that what we are dealing with in The Park and Stranger Things are parallel but differing constructions of single motherhood. Both are oriented toward telling the stories of single mothers searching for their missing sons and enduring the horrors and trauma that result from their sons’ disappearances. But while Stranger Things might work to recast single motherhood as a site of maternal power (to varying degrees of success, depending on what side of the Valentine/Shepherd argument you are), The Park perpetrates the idea of single motherhood as a site of danger, monstrosity, instability, and abnormality. And at the heart of such characterizations is the idea of credibility—for, we are asked to doubt Lorraine’s credibility, stability, and, ultimately, ability to mother due to her construction as mentally unstable, while, on the other hand, we are asked to believe Joyce, to see her not as a dangerously unstable mother but as one who is determined, as one who will face any monster to save her son. Thus, it seems to me that the conversation occurring between The Park and Stranger Things, between Lorraine and Joyce, begins to complicate our understanding of how maternal power can either be reimagined or stifled through representations of single mothers.