I ended my blog post last week with some lingering questions I still have about the representation of single motherhood as a destructive and dysfunctional force in The Park, which doesn’t feel like a particularly satisfying way to wrap up my examination of the game. So I want to spend some more time thinking through these questions and these lingering, needling thoughts—questions and concerns that I want to restate here:

I ended my blog post last week with some lingering questions I still have about the representation of single motherhood as a destructive and dysfunctional force in The Park, which doesn’t feel like a particularly satisfying way to wrap up my examination of the game. So I want to spend some more time thinking through these questions and these lingering, needling thoughts—questions and concerns that I want to restate here:

Do representations of “dysfunctional” mothering work to reify the patriarchal norms of good and bad mothering? Or can such representations work to challenge and unsettle such norms in an effort to reimagine different modes of mothering? And where does the maternal horror of games like The Park reside in such representations?

Tammy Oler discusses recent iterations of bad motherhood in horror films in “The Mommy Trap,” in which she explains, “Mothers aren’t hard to find in horror. The genre has more than its share of murderous matriarchs and fierce mama bears, and it’s always been awash in the bloody spectacle of birth.” But even though monstrous mothers are prevalent characters in horror, Oler also interrogates the boundaries of such representations: “Even by the ghastly standards of horror films, which will gladly traffic in serial killers, monsters, and demons, a mother murdering her child is typically beyond the pale.” However, Oler points out that recent horror (she uses The Babadook as one example) seems to work to challenge this boundary and to address it “head-on, imagining how trauma and the pressures of parenting can transform a mother into a terrible force, and exposing just how scary the unspoken feelings a mother can have toward her child can be.” And according to Oler, in doing so, recent maternal horror uses “genre to take a hard look at how we imagine motherhood at a time when the question of what makes a good mother is more fraught than ever.”

This question in horror films, Oler continues, is the result of the idea that “[t]here’s very little agreement about parenting these days except that other people are probably doing it wrong. And while we live in an age of parental scrutiny, mothers are still the ones who shoulder nearly all the parenting pressure. These films tap into just how terrifying and confusing it is to be a mother right now.” And this ability to “tap into” the complex nature of motherhood is what causes Oler to see value in recent iterations of maternal horror:

This question in horror films, Oler continues, is the result of the idea that “[t]here’s very little agreement about parenting these days except that other people are probably doing it wrong. And while we live in an age of parental scrutiny, mothers are still the ones who shoulder nearly all the parenting pressure. These films tap into just how terrifying and confusing it is to be a mother right now.” And this ability to “tap into” the complex nature of motherhood is what causes Oler to see value in recent iterations of maternal horror:

The powerful work of horror is that it gives voice to what frightens and disturbs us. Taken as a whole, these films surface a set of anxieties about motherhood that are too uncomfortable to admit, especially in this era of mom-shaming: that the line between good parenting and bad parenting isn’t as nearly as fixed as we’d like; that not having children is a path to more professional success; that for some, parenthood is neither a satisfying nor beneficial experience.

As such, Oler argues that horror films that represent such anxieties about motherhood “don’t offer the traditional cathartic horror-movie release of terror vanquished. But they do let women face the unspoken fears of motherhood and womanhood in our pressure-cooker era, and that is a big relief.”

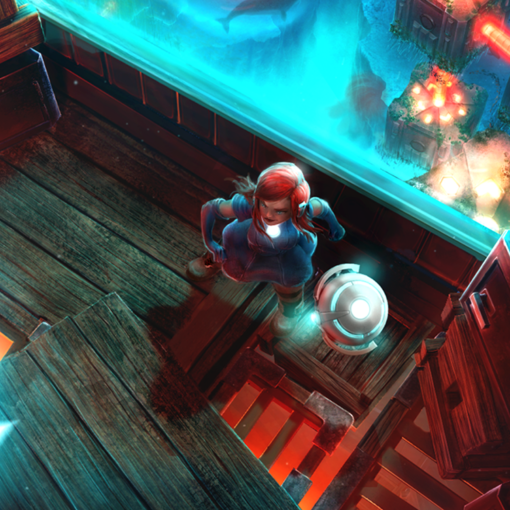

I’m wondering if the same can be said for The Park though—that is, I’m wondering if the game’s intention in its depiction of Lorraine’s struggles with being a single mom is to allow for the relief of facing the “unspoken fears of motherhood” and to complicate our understanding of what it means to be a mother. On one hand, it does seem that the game works to give us insight into Lorraine’s situation in a way that might be asking us to feel empathy for her—based on the comments she makes as she searches for her son Callum in the vacant amusement park, we come to find out that Callum’s father died when Lorraine was three months pregnant, which forces Lorraine to have to go through both pregnancy and the responsibility of motherhood on her own. This context, this unforeseen tragedy and sudden isolation, gives us insight into the reasons why Lorraine struggles with being a mother and views her maternal role negatively, and this insight, then, might be an attempt to complicate our understanding of motherhood.

Then again, that may be giving the game too much credit. Because, ultimately, I don’t think Lorraine’s backstory, her context of tragedy and isolation, and her complicated struggles with her own mothering are meant to construct her as a sympathetic mother; rather, all this seems to be meant to construct her as a monstrous one. And I think a lot of that is due to the manner in which the game concludes, for the game ends by leading us to believe that Lorraine is a murderous mother—that she has killed her son, which Lorraine herself eerily foreshadows earlier on in the game when she says about Callum, “I can save him. There will be pain. But I love him and in the end, he will understand why.” So, while this statement seems to frame her act of murder as being done in the name of (motherly) love, it also highlights Lorraine’s monstrous mothering, for it reveals her inability to discern right from wrong, good from evil, monstrous motherhood from virtuous motherhood.

Then again, that may be giving the game too much credit. Because, ultimately, I don’t think Lorraine’s backstory, her context of tragedy and isolation, and her complicated struggles with her own mothering are meant to construct her as a sympathetic mother; rather, all this seems to be meant to construct her as a monstrous one. And I think a lot of that is due to the manner in which the game concludes, for the game ends by leading us to believe that Lorraine is a murderous mother—that she has killed her son, which Lorraine herself eerily foreshadows earlier on in the game when she says about Callum, “I can save him. There will be pain. But I love him and in the end, he will understand why.” So, while this statement seems to frame her act of murder as being done in the name of (motherly) love, it also highlights Lorraine’s monstrous mothering, for it reveals her inability to discern right from wrong, good from evil, monstrous motherhood from virtuous motherhood.

It also seems important to note that the game also calls all this into question; since it constructs Lorraine as a character who also struggles with mental health issues and who may potentially be hallucinating all this, we cannot trust the veracity of what we see on the screen, and so we cannot be sure that she really has killed Callum. But even though we cannot be sure of what is real and what is not, the game nonetheless frames the idea of Lorraine murdering Callum as being a possibility. And even the possibility of murder—even the possibility that Lorraine may want to murder her son—highlights the monstrosity of Lorraine’s mothering.

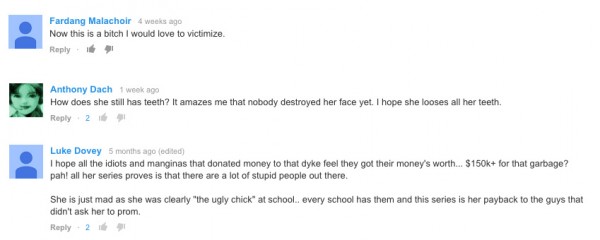

Monstrous mothers are, of course (to return to Oler’s arguments), nothing new in the horror genre. And they are definitely nothing new in video games (and I’ve talked about such representations in previous posts). And what I think is important about such patternings is the fact that, as Oler argues, recent iterations of horror have the potential to explore motherhood in more complex ways, ways that do not necessarily perpetuate mother-blaming and mother-shaming. Such potential, though, seems to be hard to come by in the narratives of video games, at least for now, and I hope that we might eventually have the opportunity to play games that feature mother characters that are not either simply demonized or victimized (or, in the case of Among the Sleep, both) and that are, instead, rendered in more complex, multidimensional ways.