When thinking about the ways motherhood comes to be framed in games, some questions that often come to mind are–how do games represent motherhood? What assumptions, biases, and social norms are games manifesting? Are they perpetuating normative, patriarchal constructions of motherhood? Or are some games working to complicate such constructions? Can certain games be said to be working to disrupt such norms? That is, are there games that allow us to think about motherhood in new, more expansive ways?

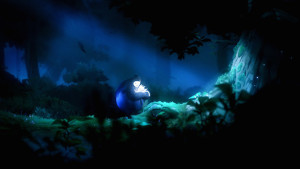

To be sure, these are questions that the two of us have been thinking through specifically in relation to Ori and the Blind Forest, a game that not only features multiple maternal figures but also, we argue, centers on and celebrates their maternal roles.

Before we can get into the ways the game represents motherhood and maternal roles, a little summary is perhaps needed (spoilers ahead). Ori and the Blind Forest starts out with a storm, in which a newborn spirit named Ori is separated from the Spirit Tree of Nibel and is found by the benevolent Naru, a dweller of the forest. She raises Ori, and the two of them spend their days playing in the Forest and gathering fruit together. However, the Forest is going blind, dying due to an unknown cataclysm, and soon there is no food for those who live in the forest. Naru gives the last of her food to Ori and eventually succumbs to starvation.

Before we can get into the ways the game represents motherhood and maternal roles, a little summary is perhaps needed (spoilers ahead). Ori and the Blind Forest starts out with a storm, in which a newborn spirit named Ori is separated from the Spirit Tree of Nibel and is found by the benevolent Naru, a dweller of the forest. She raises Ori, and the two of them spend their days playing in the Forest and gathering fruit together. However, the Forest is going blind, dying due to an unknown cataclysm, and soon there is no food for those who live in the forest. Naru gives the last of her food to Ori and eventually succumbs to starvation.

Now orphaned, Ori ventures out into the Forest and collapses but is soon revived by the Spirit Tree. Shortly after this, Ori meets Sein, who calls himself the “light and eyes of the Spirit Tree,” and who guides Ori on their journey to restore the Forest by restoring the light to the three elemental spirits that support the Forest. However, their journey is impeded by Kuro the Owl, Ori’s main antagonist, and we soon come to discover Kuro’s motivations for this antagonism; when Ori was lost in the storm, the Spirit Tree released a blinding light to try to find them. The light and energy killed Kuro’s children, and she stole Sein to prevent the Tree from killing the last, unhatched child she had.

Along the way, Sein and Ori also meet Gumo, a creature that is the last of his kind, as all others have perished due to the Blinded Forest. Ori saves Gumo, and in repayment for their kindness and for their efforts in working to restore the Forest, Gumo brings Naru back to life. After restoring the final elemental, Ori is captured by Kuro and seemingly killed; Naru finds their unconscious body and weeps. Kuro sees this act of mourning and is reminded of her own family–seeing that Naru weeps for her child and realizing that the imbalance of the forest will eventually take her last child as well, Kuro sacrifices herself to restore the Forest. After this act of self-sacrifice, the game ends with Ori helping raise new spirits with the Spirit Tree, and Gumo and Naru raising Kuro’s hatchling.

It is important to note that, though the game is named Ori and the Blind Forest and Ori is the protagonist, ultimately, the game is not about them. The game is about the two mothers, Naru and Kuro. The game, then, centers on these two characters in a way that highlights the power of maternal figures.

Naru and Kuro present two different views of motherhood, where neither mother is better than the other. In fact I (Jynx) would say both are fantastic mothers in a world that is seemingly against them both. Naru and Kuro both will do anything for their family and their kin, even if the cost is great. Ultimately, both Kuro and Naru give their lives to protect others, though Naru is given hers back due to Ori’s kindness; and Kuro’s life could be said to continue through her hatchling, perhaps.

Naru and Kuro present two different views of motherhood, where neither mother is better than the other. In fact I (Jynx) would say both are fantastic mothers in a world that is seemingly against them both. Naru and Kuro both will do anything for their family and their kin, even if the cost is great. Ultimately, both Kuro and Naru give their lives to protect others, though Naru is given hers back due to Ori’s kindness; and Kuro’s life could be said to continue through her hatchling, perhaps.

These two different representations of motherhood–both Naru’s motherhood and Kuro’s–bring to mind Sara Ruddick’s discussion of maternal thinking in Maternal Thinking: Toward a Politics of Peace. In this text, Ruddick seeks to disrupt the seeming powerlessness of the mother that results from the patriarchal configurations of family and parenting by arguing for the power of maternal thinking, the power of maternal thought. While Ruddick constructs maternal thinking as an example of “womanly” thought, she also argues that maternal thinking is not biologically determined but is rather a “social category,” one that both women and men can express in a variety of ways.

This social categorization of maternal thinking—the idea that both women and men can express maternal thinking—allows Ruddick to argue for social reform and to work to (re)claim motherhood as a site for power and agency. Yet, while Ruddick’s argument for the power of maternal thinking does seek to reclaim and empower women through the centering of motherhood, it also does so through problematically essentialist assertions of a sort of mystical or magical maternal power—power that Ruddick nonetheless perpetuates as being grounded within the domestic sphere. Yet, this reclaiming of power, at least, allows us to (re)imagine ways of decentering the power of the father and ways of reframing the power of the mother.

Indeed, this power of the mother, this power of maternal thinking, is something that seems to be made manifest through the characterizations of Naru and Kuro. Because maternal thinking seems to be at the heart of their actions throughout the game, for all their actions seem motivated by their desire to love, care for, and protect their children. But something the two of us have also been trying to work through is wondering whether or not these characterizations, these reflections of maternal thinking as they are manifested in Ori and the Blind Forest, are limited in any way–whether or not these representations, like Ruddick’s discussion of maternal thinking itself, are in any way also problematically essentialist assertions of a mystical maternal power. Whether or not they might perpetuate certain traits or motivations or desires as being inherently maternal, such as the construction of (good) mothers–like Kuro and Naru–as being self-sacrificing, as willing to do anything for their families, as being primarily, and often solely oriented toward protecting and caring for their children. Because, since both Kuro and Naru sacrifice themselves for their children (Naru at the beginning of the game and Kuro at the end), the game does, at times, seem to rely on normative constructions of motherhood and maternal roles in order to convey the (maternal) power of these two characters.

Yet, even though this potentially essentialist stereotyping of motherhood does manifest itself in the representations of Kuro and Naru, we might also see motherhood as something that shines within Ori as well. Interestingly enough, most people seem to code Ori as male (though Moon Studios has said that Ori is genderless and thus pronouns are left up to the player). However, Ori begins to reflect Naru’s power and shows motherhood traits as well–traits like self-sacrifice, like the care and protection of others, and, ultimately, like the restoration and giving of life. While it may be restrictive to simply call these traits exemplifications of motherhood, it begs the question of whether Ori begins to break down the stereotypes of motherhood and fatherhood as well–in that, in the game, parenthood is ultimately defined as the work of caring for others and as the ability to find happiness and safety among one’s friends and family.

Perhaps the fact that such traits and definitions are situated within Ori’s genderless body speaks again to Ruddick’s maternal thinking–that is, maternal thinking as a fluid power that one can express regardless of one’s embodiment or positionality. Perhaps the game’s fluidity in its representations of the ways maternal thinking can be embodied blurs the boundaries between parenting roles and destabilizes the normative, binaristic ways we often conceive of motherhood and fatherhood. And perhaps this blurring, this fluidity, allows Ori and the Blind Forest to reimagine, reframe, and redefine family structures as well–because this fluidity results in the fact that family, in the game, is not simply based on biological ties but on unbounded love as the basis for the formation of lasting kin.

Perhaps the fact that such traits and definitions are situated within Ori’s genderless body speaks again to Ruddick’s maternal thinking–that is, maternal thinking as a fluid power that one can express regardless of one’s embodiment or positionality. Perhaps the game’s fluidity in its representations of the ways maternal thinking can be embodied blurs the boundaries between parenting roles and destabilizes the normative, binaristic ways we often conceive of motherhood and fatherhood. And perhaps this blurring, this fluidity, allows Ori and the Blind Forest to reimagine, reframe, and redefine family structures as well–because this fluidity results in the fact that family, in the game, is not simply based on biological ties but on unbounded love as the basis for the formation of lasting kin.