Last weekend I finally made it to the theater (with Alisha–she was brave) to see Jordan Peele’s film Get Out (2017). I’ve wanted to see it for a while, but I was pretty sure that I didn’t want to see the film alone. Miraculously I had avoided spoilers in the two months since the film was released, but (like everyone else) I knew the basic premise. Get Out was a scary film based on being Black in America. And here I say scary and not horror with great intentionality (but more on that later). This post will make vague references to the narratives of the media discussed, but will make every attempt to avoid specific spoilers.

My last week of media consumption has been one filled with narratives of terror. From seeing Get Out in the theater, The Handmaid’s Tale (2017) on Hulu, and playing Little Nightmares (Tarsier Studios, 2017), I have spent a lot of time thinking about when horror ceases to be horrible and becomes terrible instead. There are some pretty fine distinctions at play. Horror is generally defined as

a : painful and intense fear, dread, or dismay

b : intense aversion or repugnance

While terror is defined as

a : a state of intense fear

b : a cause of anxiety

In the strictest sense of the word there is little horrible about any of these texts because horror seems to suggest that there is something unbearable and unusual about them, but they are terrible in that they can bring about intense fear and anxiety.

In what follows I what to think about what horror feels like when it just feels like more of the status quo. While I am going to start with talking about film and then move into games I think that it is most important to point out that (for me) this is more about narratives. Narratives that exist in fictionalized texts and the real world alike.

In “Match Made in Hell: The Inevitable Success of the Horror Genre in Video Games,” Richard Rouse III writes

Suspense-driven horror films have long focused on life and death struggles against a world gone mad, with protagonists facing powerful adversaries who are purely evil.

This rings particularly true in the media that I have been consuming this week. They are all a reflection of the world that seems to have already unfolded before it or that is in the process of unfolding. From race relations to gender relations to the treatment of children in the world, the world is revealing itself to be pure evil.

“If there’s too many white people I get nervous.”

Get Out is a film about dealing with the particular brand of racism that comes wrapped in white liberalism in the United States. Yes, the film’s wrapping is extreme, but not so extreme that every person of color that I have talked to about the film did not recognize the goings on in the film on some level. The not so subtle references to Black male sexuality and the commodification of such, affirmative action, and genetic superiority when it comes to sports. The almost funny references to the tension that one feels when one is assimilated into a culture that is not their own at the expense of their own. We see portrayed what we feel when vestiges of self are all that remain.

Get Out is a film about dealing with the particular brand of racism that comes wrapped in white liberalism in the United States. Yes, the film’s wrapping is extreme, but not so extreme that every person of color that I have talked to about the film did not recognize the goings on in the film on some level. The not so subtle references to Black male sexuality and the commodification of such, affirmative action, and genetic superiority when it comes to sports. The almost funny references to the tension that one feels when one is assimilated into a culture that is not their own at the expense of their own. We see portrayed what we feel when vestiges of self are all that remain.

One of the more terrible things in my experience with Get Out was not in the film itself (or at least not entirely so). At one point in the film there was an extremely tense moment that is all too well known by Black folks and when it resolved itself laughter rose from the crowd. Me? I sat there with tears streaming down my face wanting to scream at them all to shut up. Wanting to take that time to explain why it was such an important moment and why there was nothing even remotely fucking amusing about what we had just seen transpire on the screen. For them it was a horror movie moment, for me…sheer terror.

“Normal is what you are used to.”

I was most skeptical about watching The Handmaid’s Tale, but I finally gave in one night when I needed something to watch while doing a geeky cross-stitch project. This newest adaptation held no interest for me because it seemed (seems?) to be making an attempt to erase racism from the equation when doing a critique of conservative, patriarchal, Christianity. This is something that played a big role (for me) in the original novel and in our current political climate. So while some women heralded this new adaptation of the novel as representative of the struggle of women and liberals under the current administration, it seems that this is just another opportunity to ignore the intersectional oppression of women of color even in the (re)creation of Margaret Atwood’s dystopia.

I was most skeptical about watching The Handmaid’s Tale, but I finally gave in one night when I needed something to watch while doing a geeky cross-stitch project. This newest adaptation held no interest for me because it seemed (seems?) to be making an attempt to erase racism from the equation when doing a critique of conservative, patriarchal, Christianity. This is something that played a big role (for me) in the original novel and in our current political climate. So while some women heralded this new adaptation of the novel as representative of the struggle of women and liberals under the current administration, it seems that this is just another opportunity to ignore the intersectional oppression of women of color even in the (re)creation of Margaret Atwood’s dystopia.

When I first read The Handmaid’s Tale as an undergraduate student it felt like a dystopian novel. I could see glimpses of possibility in calls for the revocation of Roe v. Wade and the backlash toward mothers in the 1980s who had left the home to return to the workforce. There was a constant stream of complaints detailing how feminism was ruining America. But 30 years later we see many of the “horrors” of the Atwood novel being legislated into existence. Religious freedom acts, anti-abortion laws, stand your ground laws, and so many more. The more time passes, the more people become accustomed to it and the more normalized it becomes. But let me be a constant reminder…this is not normal.

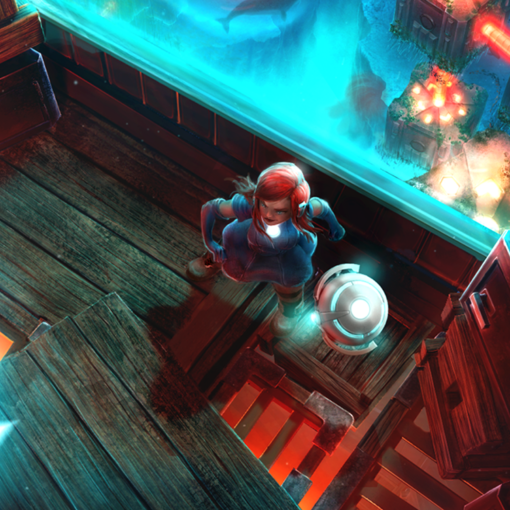

Little Nightmares

As we watch endless news stories about free lunch programs coming to an end, lunchroom staff throwing away the lunches of children who have no money remaining on their lunch accounts, or even worse forcing them to clean the tables of their classmates in order to earn their lunch it seems especially timely to play a game that is ultimately about hunger.

While some see Little Nightmares‘ Six’s (the protagonist) hunger as being about greed and obesity, to me it seems to be more about what those left hungry while others feast experience and how they respond to and grow based on that hunger. It’s about how the poor may ultimately respond to a forever full of oppression. While there is much of the grotesque present in Little Nightmares, I would argue that it is not the horror that we experience in the game, but that Six’s aching hunger, questing, avoiding those who would eat her, and what she herself is becoming. Little Nightmares is less about living through grotesque versions of our own childhood dreams and more about a revolution of sorts.

While some see Little Nightmares‘ Six’s (the protagonist) hunger as being about greed and obesity, to me it seems to be more about what those left hungry while others feast experience and how they respond to and grow based on that hunger. It’s about how the poor may ultimately respond to a forever full of oppression. While there is much of the grotesque present in Little Nightmares, I would argue that it is not the horror that we experience in the game, but that Six’s aching hunger, questing, avoiding those who would eat her, and what she herself is becoming. Little Nightmares is less about living through grotesque versions of our own childhood dreams and more about a revolution of sorts.

Through all of this I constantly find myself coming back to one question. One that I have asked myself over and over (and with far more frequency) in that last 6 months or so. How do we continue to live when our lives fall so neatly within the genre of survival horror? What can we do to get those around us to understand what it feels like to be in that position. To understand that our torment is not a moment of comic relief, that our bodies are our own and that robbing us of the right to control them is little better than using us as brood mares, and to acknowledge the fact that in a country where 2% of the population have more wealth than the other 98% it is our obligation to make sure that those in need have their basic fucking needs met. Today is one of many days that I feel that (regardless of the work that I do) I am seeing the world from the Sunken Place. A place that I can see and hear clearly, but that I can not interact with or make any changes in. And, trust me, that is far more horrific than any film ever made.