Over the years — and particularly, in the last year — the notion that game reviews should be objective, depoliticized, or both, has arisen time and time again, and been debated, discussed and parodied to oblivion.

But who are the people asking for objective game reviews? Who thinks they’re possible, and who wants them? It’s a question worth asking, because the problem with objective reviews goes beyond one of simple bias. Sure, we all have inherent biases, as gamers; we prefer certain genres to others, we laud this franchises and that mechanic over others, often for no objective reason. But there’s another reason objective reviews, possible or not, are deeply exclusive: attempts to objectively review games erase the reviewer’s life and experience and flattens the reviews themselves. That is to say, there are many factors beyond preferences and biases that inform my experience with a game: having been born as, and lived as, a woman, being married to a man and birthing children, having grown up where and how I did — all this and more affects my experiences in and with a game and gives me a different lens through which to analyze and critique specific cultural references within it.

A female reviewer may not have the same experience as a male reviewer. A black reviewer may not have the same experience as a white reviewer, an American reviewer as a British reviewer, a lesbian reviewer as a heterosexual reviewer, a cis reviewer versus one who is transgender, and on and on. Our experiences and very personhood inform not only our biases but the things we see and notice in a game and the way we read its plot and characters, and the only way we can expect so-called objective reviews that do not address these inherent differences is if we are writing from a position of hegemony for an audience made up of the same dominant, homogenous culture.

In other words, one might call for objective reviews if the assumption was primarily white cis-men writing for a primarily white cis-male audience, and expecting objective reviews is just another way to continue excluding “fringe” members of the community.

But are we on the fringes? The numbers continually reflect changing demographics among those who play games, and more and more outlets are offering platforms to voices that once went virtually unheard in gaming. Social media, too, has added its own layer of access and amplification even when the largest press sites remain largely white and male. And as that ragged chorus rises, mismatched, uneven, representing the intersections of multitudes of experience, another rises as well, calling for those differences of experience to be flattened.

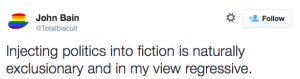

The idea that games shouldn’t be political, and shouldn’t be read by critics and scholars as political, is not only nonsense, but dangerously exclusionary. We are progressing not in spite of our hearing more voices in gaming and gaming culture but because we are hearing them and acknowledging the wealth of lived experience those voices bring to the table.

The idea that games shouldn’t be political, and shouldn’t be read by critics and scholars as political, is not only nonsense, but dangerously exclusionary. We are progressing not in spite of our hearing more voices in gaming and gaming culture but because we are hearing them and acknowledging the wealth of lived experience those voices bring to the table.

This progression brings with it change, change in the way reviews are written and received, and in the way various communities talk about games. That there even are various communities beyond simple designations of fandom is itself a change, but after the polarizing events of the last year, and the rise in presence and visibility of women in particular at E3, it’s hard to ignore that change is happening, though more slowly for some groups than others. For the dominant group, change can be alarming; change erodes the very foundation of a comfortable world, jerking away footholds and pulling down walls to allow access to those who have never had it. But the change is coming. It’s already here, and will continue to spread. Those given voice will not now be silenced.

5 thoughts on “Objective Game Reviews as Hegemonic Erasure?”

I’m very curious about what makes ‘objectivity’ seem plausible to some people. Partly the issue is me. I exist in a social circle predominantly formed of queer academics and artists. We’re not a group predisposed to seeing the plausibility of such a concept.

But as you mention, calls for objectivity largely revolve around shutting out the views of less powerful and marginalised groups. It requires not only setting up the position of the speaker as a default but then also disavowing knowledge of the position in the first place.

There’s some serious psychic gymnastics involved in the call to objectivity especially in relation to something as ‘textual’ as the review of a video game.

It baffles me, and I think objectivity is a dangerous concept. But the little psychoanalyst in my head also finds it really fascinating as a thing in which people believe.

Well said. Looking at the contemporary news media, I find myself struggling with the notion of objectivity, as it hardly seems to exist amongst all the slant, but people still often perceive these outlets as objective and thus take what is said at face value. Dangerous indeed.

You miss the point made when people ask for objectivity. They aren’t asking for 100% objectivity but that the attempt to be as objective as possible is there:

You don’t like this portrayal of X?

Is the issue of X on your mind?

Could you be biased?

Would that influence your review?

Would that influence your audience?

Inform your readership accordingly.

Objectivity achieved.

That’s your job as a journalist otherwise you’re simply a writer and that’s cool, no shame in being a writer, you just aren’t a journalist.

Not only are we not journalists – did you notice where you were? Let me refer you to our about page – but journalism is not being performed when one is writing a review in general. Journalism is about news and information (pure information, i.e., fact), or things that can be objective, even if presented with slant or bias, as often seen in news media with clear organizational slant, but still based in facts and information. Observation falls into this, but still must be presented with objectivity.

Reviews, on the other hand, are based in experience, which can include both information and facts, but these things often do not take center stage outside of, say, consumer reports. Let’s shift the example to cars. In a consumer report, or review, of a car, specs might be dominant. Here’s the mileage, the horsepower, etc. The reviewer/writer might then talk about the feel of the interior, something that is inherently subjective rather than objective, as whether or not a car seat is plush and comfortable is a personal judgment.

Reviewing media is usually more like the simple act of sitting in the seat. We don’t refer to film reviewers and critics as journalists, nor book reviewers, and on and on. But that is different than playing a game, which is interactive. You can interact with a movie in some ways, and with a book, but you can also passively absorb the content.

Playing a game, then, that is working at least largely as it should (not broken, I mean) is about the whole experience of driving the car, from sitting in the seat to feeling the steering wheel to performing specialized maneuvers or not. The write-up may include specs, but no one’s there for specs, usually; we’ve already seen that information. Unless it’s a PC game heavily dependent on hardware, we’re not usually talking about how it runs. Console experiences, after all, will be largely the same in terms of technology. But the game itself is changeable based on the experience. You cannot separate that from the identity of the reviewer. As a reader, the best you can do if you want “objectivity” is to find reviewers who seem to experience games similarly to the way in which you experience them… and that may be the center of this months-long ebb and flow of calls for objectivity. Ten years ago, even five, or three, there was more homogeneity across game reviewers. Now, however, more people have platforms, and we see a wider spectrum of people performing game review. What looks like bias, then, is simply the march of progress. Don’t like reading about how a woman who might be a feminist experiences a game? Read a review by a man who’s not. Problem solved. Others can perform review and it will not change anyone’s experience of and with a game.

Well written. The version of ‘objectivity’ you present toward the end of your comment, that of finding reviewers with similar taste, for me brings to mind Donna Haraway’s essay ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’ (such a beautiful title…the rhythm of it!). Perhaps one could view reviews, as well as science, through the lens of the concept of ‘Situated Knowledges’?

Different reviewers will be suited to seeing certain aspects of a game, and be unable to, or find it difficult to, perceive other aspects.

From that my ‘situation’ causes me (:D) to be tempted by a proposal: the best way to improve the quality of reviews (of games especially because of the interactivity) would not be to remove aspects of the author from the review but rather to encourage reviewers to inject their feelings, biases and subjectivity even more readily and openly into their reviews.

My thought being that this may perhaps provide information useful in assessing whether one might experience a game similarly to the reviewer in question?

After all, even if a reviewer doesn’t acknowledge their position it is still there; it still affected their experience of the game. A review of a game may best be conceived of not as a review of an external object but as the review of an interaction. In the same way that when I analyse an interview transcript between me and another person the analysis is as much an analysis of me as of the participant – even if I barely speak – perhaps a review of a game should be just as much a review of the reviewer and their relation to the game as it is a review of a game?