I’ve played about an hour and a half of The Magic Circle, and, to be completely honest, I haven’t yet figured out whether or not I like it. I think I do. But I’m not sure. I’m mainly confused, but not really in a way that makes me annoyed or irritated or frustrated. I’m confused in a way that makes me want to keep playing. And for a game that seems to be all about metanarrative, that seems to be the point.

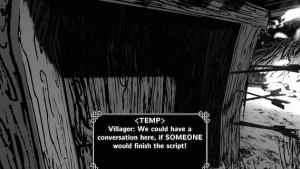

The Magic Circle, released a couple weeks ago on July 9th by Question Games (which seems to be more a command than a company name), boasts a development team consisting of people who previously worked on games like BioShock and Dishonored and a voice cast that includes James Urbaniak (aka the voice of Dr. Venture on The Venture Brothers) and Ashly Burch (who was the guest on a recent episode of our podcast). These people have come together to create a game that, by nature, seems tricky to attempt to summarize (but here goes nothing). Ultimately, it’s a game about a game, or, really, it’s a game about games in general—about game development and the process of making them. More specifically, it’s a game about an unfinished (and fictional) game, one that’s been unfinished for years, which we play through in the role of a QA tester as the developers (who take on the in-game appearance of disembodied eyes floating above us) watch and comment on the sorry state of the game-world around us. As we explore the game and its environment, we come to learn a bit about why it’s in the state it’s in, reasons ranging from lack of funds to clashing developers’ egos. We eventually encounter a character in the game who asks for our help, which we must do by taking control of the game from the inside in order to work to (finally) complete the game.

The Magic Circle, released a couple weeks ago on July 9th by Question Games (which seems to be more a command than a company name), boasts a development team consisting of people who previously worked on games like BioShock and Dishonored and a voice cast that includes James Urbaniak (aka the voice of Dr. Venture on The Venture Brothers) and Ashly Burch (who was the guest on a recent episode of our podcast). These people have come together to create a game that, by nature, seems tricky to attempt to summarize (but here goes nothing). Ultimately, it’s a game about a game, or, really, it’s a game about games in general—about game development and the process of making them. More specifically, it’s a game about an unfinished (and fictional) game, one that’s been unfinished for years, which we play through in the role of a QA tester as the developers (who take on the in-game appearance of disembodied eyes floating above us) watch and comment on the sorry state of the game-world around us. As we explore the game and its environment, we come to learn a bit about why it’s in the state it’s in, reasons ranging from lack of funds to clashing developers’ egos. We eventually encounter a character in the game who asks for our help, which we must do by taking control of the game from the inside in order to work to (finally) complete the game.

All of this is super meta, and The Magic Circle makes clear its metanarrativity from the get-go, for the opening scene of the game involves the fictional creator talking about what he wants the opening of the game to look like over a montage of whiteboard notes and sketches—in other words, the opening of the game is about the opening of the game. It’s about the process of making it. And the rest of the game (or, at least, what I’ve encountered of it so far) seems to follow suit, engaging in parodic metanarrative and dark comedy as a means of poking fun at (or with) developers, players, and the industry at large.

All of this is super meta, and The Magic Circle makes clear its metanarrativity from the get-go, for the opening scene of the game involves the fictional creator talking about what he wants the opening of the game to look like over a montage of whiteboard notes and sketches—in other words, the opening of the game is about the opening of the game. It’s about the process of making it. And the rest of the game (or, at least, what I’ve encountered of it so far) seems to follow suit, engaging in parodic metanarrative and dark comedy as a means of poking fun at (or with) developers, players, and the industry at large.

Indeed, the game’s metanarrativity extends beyond the confines of the game itself; for example, the game’s website takes the form of a fictional “Kickbackr” page (although a link at the top of the page allows us to disable the meta-text if desired), and a letter from an anonymous member of the fictional development team was also released as a means of heralding the game’s Early Access availability on Steam. I find all these methods—both within the game and without—to be fun and playful, and it’s fascinating to see a game engaging in parody and critique in these ways.

That said, the game’s critique seems to be painted in fairly broad strokes; one moment the game parodies problems with funding (which resulted in the complete scrapping of the hero’s weapons) and the next it makes a passing dig at the fictional creator’s failure to be mindful of issues of diversity. I think it’s great and ambitious for The Magic Circle to attempt to explore all these issues, but, so far, its exploration seems like it could be more focused and less rushed.

That said, the game’s critique seems to be painted in fairly broad strokes; one moment the game parodies problems with funding (which resulted in the complete scrapping of the hero’s weapons) and the next it makes a passing dig at the fictional creator’s failure to be mindful of issues of diversity. I think it’s great and ambitious for The Magic Circle to attempt to explore all these issues, but, so far, its exploration seems like it could be more focused and less rushed.

And while the game’s critique seems rushed, its gameplay and pace feels (at least, during the first hour of the game that I’ve played so far) a bit slow, although it seems the potential for creative gameplay is there. For instance, one of the things the game allows us to do is trap certain creatures (as well as some inanimate objects) and alter their behavior and characteristics in order to, potentially, make these creatures work for us and solve the puzzles we face. I haven’t had much opportunity to do this yet in the time I’ve played (and so far, the puzzles I have encountered seem fairly basic), and while I hope the game will have me make more use of such actions in more creative ways as I get further into the game, it seems that such activities could be utilized more fully and much sooner in order to allow the gameplay to be as engaging and weird as the game’s metanarrative.

And while the game’s critique seems rushed, its gameplay and pace feels (at least, during the first hour of the game that I’ve played so far) a bit slow, although it seems the potential for creative gameplay is there. For instance, one of the things the game allows us to do is trap certain creatures (as well as some inanimate objects) and alter their behavior and characteristics in order to, potentially, make these creatures work for us and solve the puzzles we face. I haven’t had much opportunity to do this yet in the time I’ve played (and so far, the puzzles I have encountered seem fairly basic), and while I hope the game will have me make more use of such actions in more creative ways as I get further into the game, it seems that such activities could be utilized more fully and much sooner in order to allow the gameplay to be as engaging and weird as the game’s metanarrative.

Yet, in spite of these limitations, I’m fascinated by what it is the game seems to be attempting, although I’m still working to unpack what it is exactly that the game is trying to do. Perhaps the title of the game might clue us in—the idea of the magic circle as the membrane that shields the world of the game, that protects the game’s inside world from that of the outside one. But this membrane is permeable and porous, as the game’s construction of metanarrative seems to imply, and it is this exploration of fiction and reality, of digital media and gaming culture, of the process of developing games and the process of playing them that makes me want to keep playing this one. It makes me want to use my own process of playing as a process of examining the manner in which The Magic Circle might allow us to think about all the different and creative ways that video game narratives might operate.

Yet, in spite of these limitations, I’m fascinated by what it is the game seems to be attempting, although I’m still working to unpack what it is exactly that the game is trying to do. Perhaps the title of the game might clue us in—the idea of the magic circle as the membrane that shields the world of the game, that protects the game’s inside world from that of the outside one. But this membrane is permeable and porous, as the game’s construction of metanarrative seems to imply, and it is this exploration of fiction and reality, of digital media and gaming culture, of the process of developing games and the process of playing them that makes me want to keep playing this one. It makes me want to use my own process of playing as a process of examining the manner in which The Magic Circle might allow us to think about all the different and creative ways that video game narratives might operate.