I read an article by Margaret Atwood recently in which she discusses the idea of freedom and argues that, today, we are “double-plus unfree” due to the fact that, as Atwood puts it, we have “handed the keys to those who promised to be our defenders but who have become, perforce, our jailers.” In other words, Atwood argues that we are governed by fear and have surrendered much of our freedom as a result; or, as she asks, “Are we turning our entire society into a prison? If so, who are the inmates and who are the guards? And who decides?”

I read an article by Margaret Atwood recently in which she discusses the idea of freedom and argues that, today, we are “double-plus unfree” due to the fact that, as Atwood puts it, we have “handed the keys to those who promised to be our defenders but who have become, perforce, our jailers.” In other words, Atwood argues that we are governed by fear and have surrendered much of our freedom as a result; or, as she asks, “Are we turning our entire society into a prison? If so, who are the inmates and who are the guards? And who decides?”

What strikes me about her argument is the manner in which she specifically discusses digital technology as playing a big role in all this:

Digital technology has made it easier than ever to treat people like domesticated animals farmed for profit. You can no longer rent a car or a hotel room or buy much of anything without a credit card, which leaves a digital trail wherever it goes. You’re told you need a social security card, a health card, a driver’s licence, a bank card, a bunch of passwords. You need an “identity”, and that identity is digital. All your numbers and passwords – all the data that identifies you – is supposed to be private, but as we know by now, the digital world leaks like a sieve, and security on the internet is only as good as the next mastermind hacker or inside-job data thief. The Kremlin has gone back to using typewriters for a good reason: it’s a lot easier to smuggle a memory stick out of a secure area than it is to make off with a big stack of papers.

This idea of a “digital identity,” one that’s potentially and insidiously restrictive and insecure, harkens back to some of the concerns Atwood expresses in her 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale, but, here, she does seem to complicate her concerns by noting that these technologies can have positive effects too, which causes her to argue that all technology “is a double-edged tool, and the very internet that has too many data-leaking holes in it also allows words to travel quickly. It’s easier to reveal abuses of power than it once was; it’s easier to sign petitions and to protest. Though even that freedom is double-edged: the petition you sign may be used by your own government in evidence against you.” Ultimately, by discussing technology and digital freedom in this way—as “double-edged”—Atwood seems to revert back to taking a cautionary stance when it comes to our use of digital technologies, especially in that she concludes the article by arguing that even though “our digital technologies have made life super-convenient for us – just tap and it’s yours, whatever it is – maybe it’s time for us to recapture some of the territory we’ve ceded. Time to pull the blinds, exclude the snoops, recapture the notion of privacy. Go offline.”

This idea of a “digital identity,” one that’s potentially and insidiously restrictive and insecure, harkens back to some of the concerns Atwood expresses in her 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale, but, here, she does seem to complicate her concerns by noting that these technologies can have positive effects too, which causes her to argue that all technology “is a double-edged tool, and the very internet that has too many data-leaking holes in it also allows words to travel quickly. It’s easier to reveal abuses of power than it once was; it’s easier to sign petitions and to protest. Though even that freedom is double-edged: the petition you sign may be used by your own government in evidence against you.” Ultimately, by discussing technology and digital freedom in this way—as “double-edged”—Atwood seems to revert back to taking a cautionary stance when it comes to our use of digital technologies, especially in that she concludes the article by arguing that even though “our digital technologies have made life super-convenient for us – just tap and it’s yours, whatever it is – maybe it’s time for us to recapture some of the territory we’ve ceded. Time to pull the blinds, exclude the snoops, recapture the notion of privacy. Go offline.”

I’m generally a fan of Atwood’s work, and I think her argument here is fascinating, but I wonder if there are limitations in focusing this argument on our so-called “double-plus unfreedom” primarily on its digital manifestations. Doing so seems to work off the assumption that our digital lives and identities are separate from the rest of our lived experiences, that “going offline” is ideal (if not, as Atwood seems to admit, feasible). It also seems to work off the assumption that our digital technologies somehow result is fewer freedoms and more restrictions than other technologies or structures—that our lives are less free in digital spaces. Thus, my apprehension in all this lies in its construction of digital spaces as separate, more violent, more insidious, more restrictive; my concern, then, lies in its construction of digital spaces as being to blame for the lack of freedom we may experience today.

I’m generally a fan of Atwood’s work, and I think her argument here is fascinating, but I wonder if there are limitations in focusing this argument on our so-called “double-plus unfreedom” primarily on its digital manifestations. Doing so seems to work off the assumption that our digital lives and identities are separate from the rest of our lived experiences, that “going offline” is ideal (if not, as Atwood seems to admit, feasible). It also seems to work off the assumption that our digital technologies somehow result is fewer freedoms and more restrictions than other technologies or structures—that our lives are less free in digital spaces. Thus, my apprehension in all this lies in its construction of digital spaces as separate, more violent, more insidious, more restrictive; my concern, then, lies in its construction of digital spaces as being to blame for the lack of freedom we may experience today.

And perhaps that may be placing blame in the wrong place—or, at least, not considering, more fully, the power dynamics and structures that exist underneath all this. Because digital spaces are not the only ones in which issues of freedom may play out. However, Atwood’s discussion of these spaces, at least, allows us to begin a conversation about the idea that the manner in which issues of freedom are affected by digital technologies might speak to the manner in which issues of freedom are constrained by other underlying structures and systems of power as well.

And perhaps that may be placing blame in the wrong place—or, at least, not considering, more fully, the power dynamics and structures that exist underneath all this. Because digital spaces are not the only ones in which issues of freedom may play out. However, Atwood’s discussion of these spaces, at least, allows us to begin a conversation about the idea that the manner in which issues of freedom are affected by digital technologies might speak to the manner in which issues of freedom are constrained by other underlying structures and systems of power as well.

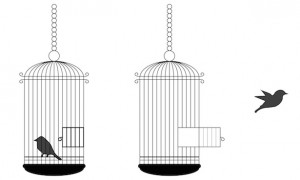

Indeed, as Atwood herself wonders at the beginning of the article, “We’re always talking about it, this ‘freedom’. But what do we mean by it? ‘There is more than one kind of freedom,’ Aunt Lydia lectures the captive Handmaids in my 1985 novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. ‘Freedom to and freedom from. In the days of anarchy, it was freedom to. Now you are being given freedom from. Don’t underrate it.’” And I wonder how these different freedoms, these freedoms to and these freedoms from, affect the ways we think about not just digital freedom but other freedoms as well. Or, as Atwood asks, “But what about us? Should we choose ‘freedom from’ or ‘freedom to’? The safe cage or the dangerous wild?” But I also wonder—are these two freedoms necessarily mutually exclusive?