Last week, I had to read Margaret Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century for a course on antebellum American literature that I’m taking this semester, and in it, Margaret Fuller critiques the gender hierarchies and relationship patterns that she saw occurring in the nineteenth century. But one moment in the text in particular struck me—namely, when Fuller discusses a woman named Countess Emily Plater and the manner in which various men, men that Fuller terms “self-constituted tutors,” took it upon themselves to “advise” Plater without her asking them to do so. And when I read this section, I chuckled and scrawled the word “mansplaining” in the margin.

Last week, I had to read Margaret Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century for a course on antebellum American literature that I’m taking this semester, and in it, Margaret Fuller critiques the gender hierarchies and relationship patterns that she saw occurring in the nineteenth century. But one moment in the text in particular struck me—namely, when Fuller discusses a woman named Countess Emily Plater and the manner in which various men, men that Fuller terms “self-constituted tutors,” took it upon themselves to “advise” Plater without her asking them to do so. And when I read this section, I chuckled and scrawled the word “mansplaining” in the margin.

Whether it’s “self-constituted tutors” as Fuller puts it or “mansplainers” as we often term it today, what we’re dealing with is men, operating from positions of privilege, condescending to women. And the underlying assumptions that result in such unasked-for explication reveal the fact that knowledge and expertise are often framed in gendered ways.

I was talking about all this with my sister over the weekend, and she, a musician in Los Angeles, brought up her own experiences with mansplainers in the music industry. From being told what songs she “should” be playing to being asked how to tune a mandolin and then being told she was wrong upon answering (she, of course, was not), my sister, it would seem, has had to consistently navigate a field of men who assume they know more about music than she does and who assume that she, then, requires unsolicited advice and correction. But my sister’s experiences aren’t unique—rather, her stories illustrate the consistent gendering of musical prowess and artistry.

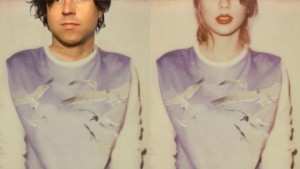

Indeed, after talking to my sister, I was reminded of an article I read recently entitled “Ryan Adams’s 1989 and the Mansplaining of Taylor Swift” in which Anna Leszkiewicz discusses Ryan Adams’s covering of Taylor Swift’s album 1989 and the manner in which many music journalists seem to be discussing it. As Leszkiewicz puts it,

Indeed, after talking to my sister, I was reminded of an article I read recently entitled “Ryan Adams’s 1989 and the Mansplaining of Taylor Swift” in which Anna Leszkiewicz discusses Ryan Adams’s covering of Taylor Swift’s album 1989 and the manner in which many music journalists seem to be discussing it. As Leszkiewicz puts it,

The media’s most highbrow music critics, the same ones who barely batted an eye at Swift’s release, have rushed forward to gush over Adams’s transformation of a cheesy pop album into something more serious. In the words of American Songwriter, Adams is “bestowing indie-rock credibility” on Swift’s album, potentially even “showing her up by revealing depth and nuance in the songs” and “giving her a master class in lyrical interpretation”.

And Leszkiewicz continues by arguing that a “whole range of publications make a similar claim that Adams’s masculine, alternative cover lifts Swift’s original to higher plains. Even reviews that laud Swift’s original achievement applaud Adams for making us realise its strength, as though Swift’s album alone could never convince us.” And what seems significant about Leszkiewicz’s critique is the manner in which it might speak to spheres other than just the music industry:

It’s a response that will be eerily familiar to women across the globe who have sat in a meeting and watched as their ideas have been shot down, only to be taken seriously when co-opted by a male colleague. Who have listened to male friends repeat their own jokes back to them, as though they had hit on something funny utterly by accident. Even with the intention of celebrating her, Ryan Adams has made it possible for dozens of music journalists to mansplain Swift’s own album to her.

To be sure, it is a response that seems eerily familiar and it’s one that we see in other spheres and other industries. In fact, we might extend this line of thinking to the film industry as well by considering the manner in which Leszkiewicz’s article speaks to Matt Damon’s recent foray into mansplaining territory; as Hoai-Tran Bui explains, “In the fourth season premiere of HBO’s Project Greenlight last night, Damon got into a bit of a tiff with African-American female producer Effie Brown. Well, it wasn’t so much of a tiff as Damon talking over her as she tried to raise an issue about diversity.” More specifically, when Brown “suggests that to get better representation in front of the camera, they should think about hiring more people of color behind the scenes,” Damon interrupts her in order to “tell her that her point is void, because a group of white producers brought up the same issue that she is raising.” And Damon’s interjection, here—one that seems to reveal the space of white male privilege that Damon occupies—prompted this (warranted) expression from Brown, one that I think sums things up quite nicely:

So, whether we’re talking about Margaret Fuller or Taylor Swift or Effie Brown, or whether we’re talking about self-constituted tutors or mansplainers (or whatever clever colloquialism it may be), what seems important to point out is the fact that the phenomenon of men explaining things to women is not a new one nor is it specific to certain spheres or domains or even time periods. Indeed, while I’ve talked mainly about the fields of film, literature and music, we’ve, of course, seen the ramifications of mansplaining in the gaming industry as well—which is something that was especially highlighted during the events of Gamergate and which is something that we need to  continue to critically interrogate and challenge. And, thus, while mansplaining may manifest itself in different ways according to different cultural contexts, it’s also just one of the ways that things like skill, knowledge, relevance, and expertise become gendered.

continue to critically interrogate and challenge. And, thus, while mansplaining may manifest itself in different ways according to different cultural contexts, it’s also just one of the ways that things like skill, knowledge, relevance, and expertise become gendered.