Last week, I read an article by Mike Mariani called “The Tragic, Forgotten History of Zombies,” and it got me thinking about the folkloric and mythological trajectory of the undead. Indeed, what strikes me about Mariani’s article is his argument that our current pop culture iterations of the zombie whitewash its origins by straying from its Haitian roots:

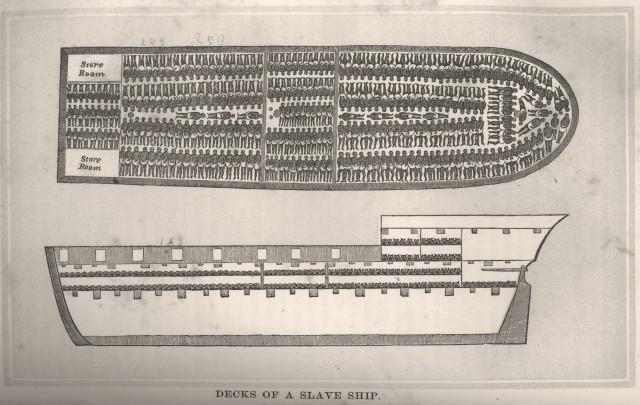

But the zombie myth is far older and more rooted in history than the blinkered arc of American pop culture suggests. It first appeared in Haiti in the 17th and 18th centuries, when the country was known as Saint-Domingue and ruled by France, which hauled in African slaves to work on sugar plantations. Slavery in Saint-Domingue under the French was extremely brutal: Half of the slaves brought in from Africa were worked to death within a few years, which only led to the capture and import of more. In the hundreds of years since, the zombie myth has been widely appropriated by American pop culture in a way that whitewashes its origins—and turns the undead into a platform for escapist fantasy.

It seems to me that Mariani has a point in this discussion of whitewashing, a point made all the clearer in his examination of the zombie’s Haitian origins: “The original brains-eating fiend was a slave not to the flesh of others but to his own. The zombie archetype, as it appeared in Haiti and mirrored the inhumanity that existed there from 1625 to around 1800, was a projection of the African slaves’ relentless misery and subjugation.” And, as Mariani continues, this folkloric archetype continues on into the 1800s, but, as it does so, it also begins to evolve as a result of its being “folded into the Voodoo religion, with Haitians believing zombies were corpses reanimated by shamans and voodoo priests. Sorcerers, known as bokor, used their bewitched undead as free labor or to carry out nefarious tasks. This was the post-colonialism zombie, the emblem of a nation haunted by the legacy of slavery and ever wary of its reinstitution.” So, interestingly, the construction of the zombie already began shifting and mutating in the 1800s, becoming, then, “a more fractured representation of the anxieties of slavery, mixed as they were with occult trappings of sorcerers and necromancy. Even then, the zombie’s roots in the horrors of slavery were already facing dilution.”

Mariani goes on to expand on the further dilution that occurs from George Romero’s construction of the zombie to those we see today—zombies that incorporate plague-like, apocalyptic, and cannibalistic undertones. But what seems interesting in Mariani’s tracking, here, of the zombie’s popular-cultural trajectory is the fact that, while he seems pretty disparaging of the zombies we see in texts like The Walking Dead, he doesn’t seem to have such problems with those that Romero created:

Mariani goes on to expand on the further dilution that occurs from George Romero’s construction of the zombie to those we see today—zombies that incorporate plague-like, apocalyptic, and cannibalistic undertones. But what seems interesting in Mariani’s tracking, here, of the zombie’s popular-cultural trajectory is the fact that, while he seems pretty disparaging of the zombies we see in texts like The Walking Dead, he doesn’t seem to have such problems with those that Romero created:

For a brief period, the living dead served as a handy Rorschach test for America’s social ills. At various times, they represented capitalism, the Vietnam War, nuclear fear, even the tension surrounding the civil-rights movement. Today zombies are almost always linked with the end of the world via the “zombie apocalypse,” a global pandemic that turns most of the human population into beasts ravenous for the flesh of their own kind. But there’s no longer any clear metaphor. While America may still suffer major social ills—economic inequality, policy brutality, systemic racism, mass murder—zombies have been absorbed as entertainment that’s completely independent from these dilemmas.

And I think this is where Mariani starts to lose me.

Because, ultimately, Mariani conceives of Romero’s heyday as being a sort of golden age for the zombie, a golden age that has since diminished, for as he argues, “The zombie is no longer a commentary on consumerist culture, as it was in the comparatively halcyon days of Dawn of the Dead; it has consumed consumerist culture.” And, as a result, Mariani concludes that pop culture has turned the zombie into a vehicle for escapism and the zombie apocalypse into an outlet for our “fantasies, functioning as an escape hatch into a world with higher dramatic stakes, fewer people, and the chance to reinvent oneself, for better or worse.”

Because, ultimately, Mariani conceives of Romero’s heyday as being a sort of golden age for the zombie, a golden age that has since diminished, for as he argues, “The zombie is no longer a commentary on consumerist culture, as it was in the comparatively halcyon days of Dawn of the Dead; it has consumed consumerist culture.” And, as a result, Mariani concludes that pop culture has turned the zombie into a vehicle for escapism and the zombie apocalypse into an outlet for our “fantasies, functioning as an escape hatch into a world with higher dramatic stakes, fewer people, and the chance to reinvent oneself, for better or worse.”

In short, while I think that Mariani’s critique of the zombie genre as a whitewashed one is one that holds water, I’m not sure I agree with his conclusions regarding the fact that zombies today, unlike, supposedly, those of the 60s and 70s, no longer afford us the opportunity to represent “the real-life horrors of dehumanization.” To make such universalizing claims about the entirety of one generation’s popular-cultural representations of monstrosity versus another’s is an oversimplification of the diverse range of texts that might be produced within a certain time period. And to privilege a certain period by nostalgically referring to it as some sort of golden age seems to problematically dismiss the texts being produced today as somehow “lesser than” without even giving them a chance.

But I also don’t want to come across as making universalizing claims myself (albeit in a different direction than Mariani)—I’m not saying that all the zombie films and television shows and comic books and literature and games being produced today are all superior to what has come before. My point is far from that. What I’m saying is that we shouldn’t necessarily dismiss them—because, even if the zombie has changed, even if the zombies today don’t look like those that came before, that doesn’t mean they, then, don’t have the capacity to represent the anxieties of our time. Perhaps they just do so in different ways. And perhaps we interact with these renderings in different ways as well, for we don’t simply read zombie literature or watch zombie movies but play zombie games as well. And the interrogation of these various layers of interactions and representations could provide us with some meaningful results, as long as we don’t render invisible the origins and lineage of the genre, as long as we no longer, as Mariani says, whitewash the zombie by omitting its roots. And perhaps we might move in this direction by thinking through things more critically—by making connections across texts, forms, time periods and, in doing so, by thinking about how such connections allow zombies to represent our anxieties and fears in even more engaging ways. Because, it seems to me, it’s the tracing of such connections (and divergences) that matters most.

2 thoughts on “Thinking Through the Undead: A Post-Halloween Reflection on the Zombie”

I very much agree with everything you say. I think Mariani has excellent points about whitewashing but their vision of today’s zombie fiction seems slightly blurred by nostalgia for Romero films, regarding the usefulness of current fiction as a place of cultural critique at least.

One thing that has always seemed striking to me that intermittently runs through zombie fiction from the mid 20th century right up to now is the zombie as representative of ‘the homosexual’. Predatory, contagious, unable to reproduce through ‘conventional’ means and so recruiting ‘our’ friends and family and neighbours. A symbol of non-productivity and a break in the reproductive cycle, and through that it links up with ideas of capitalism and productive forces.

I mention this because occasionally in the 21st century this connection has been made explicit in a way that I think is fairly new for zombie fiction. A properly 21st century development.

I’m thinking specifically of the Bruce LaBruce film ‘Otto; or, Up With Dead People’. Here the critique is reversed from that of the Romero films: heterosexual, patriarchal capitalism is represented by the living. In an age where most people perceive the end of capitalism as impossibly out of reach LaBruce gives them the impossible solution: liberation by queer zombies living beyond the death of the living capitalist system which they attempt to end by recruiting living heterosexuals into unproductive, queer undeath.

There is also, and more accessibly, the brilliant BBC drama ‘In The Flesh’ about a rehabilitated zombie (or Partially Deceased Syndrome Sufferer, as the programme labels them) of ambiguous sexual orientation attempting to reconnect with his family, and community, and resume the homoerotic relationship with his best friend that was forming at the time of his death. There is lots of social commentary themes in that series…mental health, pharmacology, community, sexuality, marginalisation (and, importantly, the communities that marginalisation forms).

I think if one takes current zombie fiction an attempts to locate social commentary and critique within it that is framed similarly to that of the Romero films then one will not find it. The framing of such commentary has definitely changed.

Awesome article, thank you for sharing! Intersection of myth and pop-culture is the best.

I can agree with the point Mariani seems to be making, that as Romero-era commentary on consumer culture, zombie storytelling has itself been consumed, digested, and regurgitated as something more palatable and less challenging to the status quo: makes me wonder about the potential meta-commentary in a story about a zombie-eating zombie! But that does not prevent the stories from informing us what the fantasy means to the current undead renaissance, it’s just that the subtext and its appeal are predictably depressing. Speaking from my perspective as a white dude from the US, current zombie fiction, (specifically the very current stuff like TWD and WWZ) speaks to fetishisized individualism without empathy against dead-eyed humans, xenophobic and defensive community-building, and justifiable physical violence. You can’t get more on-the-nose with who these themes are appealing to in the real world and why, and they are very different – even polemically opposed – to the hippie message Romero was going for when he appropriated the zombie for white pop culture consumption.

Spoiler alert: book!Rick took a hard turn early in Alexandria where he specifically realized that his xenophobia and at-all-costs survivalism was very much NOT protecting Carl in any sustainable way, and he slowly changed gears to truly value community building, and trusting in a supportive co-existence with others as a path to helping rebuild the world. Late in the game as it was, I appreciated this subversion of the apocalypse survival fantasy by Kirkman and co. I’m not sure if the show will deal heavily with those themes or not: they stand to lose more than the book in terms of mass appeal.