Alisha recently alerted me to a piece making the rounds on Facebook called “Ghoul, You’ll Be a Woman Soon: Supernatural Puberty and the Horror of Periods,” in which Emalie Soderback discusses a subgenre of film that she likes to call “supernatural-period-girl-horror.” Soderback begins this examination by laying its foundations:

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) kicked off the trend of films depicting the terror and mystery of what women are capable of (giving birth to…perhaps Satan’s baby?), and focused on a woman’s body as a vessel of horror. However, in the 1970’s, starting with William Friedkin’s The Exorcist in 1973, horror films found yet another new way of unsettling the masses—possession and evil kids. And what could be scarier than evil kids or kids with supernatural abilities? Teenage girls of course. No one understands them anyway; their bodies are changing, hormones raging—they might as well be a terrifying, demonic force, sighing and complaining in their purgatory between childhood and womanhood.

And, Soderback continues, representations of menstruation and menarche are symptomatic of a larger argument that constructs horror as “a film genre intrinsically tied to women, whether it’s placing the focus on the final survivor girl (Halloween, Scream)…or stewing in the terror of the female body and what it can create (Rosemary’s Baby, The Brood). The story of a girl going through puberty is no less frightening…what with sexual awakenings, changing bodies, and literal blood escaping the ever enigmatic and oh-so-mysterious vagina.”

And, Soderback continues, representations of menstruation and menarche are symptomatic of a larger argument that constructs horror as “a film genre intrinsically tied to women, whether it’s placing the focus on the final survivor girl (Halloween, Scream)…or stewing in the terror of the female body and what it can create (Rosemary’s Baby, The Brood). The story of a girl going through puberty is no less frightening…what with sexual awakenings, changing bodies, and literal blood escaping the ever enigmatic and oh-so-mysterious vagina.”

Indeed, the idea of blood escaping the vagina is one that, in arenas other than the horror genre, is often rendered invisible due to the stigma that has been constructed around it. This stigma, recently, was challenged by Kiran Gandhi, who “ran the London marathon while bleeding freely, sans tampon, staining her running pants. Many were shocked by it, but why?” This “why” is, to be sure, a good question, and it’s one that Gandhi works to unpack on her blog:

Although menstruation stigma is only one of many systemic factors that perpetuate gender inequality, I find it to be a rather large one that we frequently ignore. My run was about using shock factor to create dialogue around menstrual health and comfort, so that women can start to own the narrative of their own bodies. Speaking about an issue is the only way to combat its silence, and dialogue is the only way for innovative solutions to occur.

Such stigma has also been discussed in relation to the THINX subway ads in New York, a situation in which, according to THINX CEO Miki Agrawal, a representative from the company that sells the subway’s ad space told “THINX’s marketing director that a silhouette of women’s underwear would be better than putting the underwear on models. When she protested…he told her not to make it a ‘women’s issue.’” This representative (again, according to Agrawal) also asked “what a 9-year-old boy might think if he saw the ads and how his mother could explain them to him.” And what has caused outrage over all this is the fact that, as Christina Cauterucci puts it,

Most of the many ads that have plastered women in various states of undress on subway walls have been designed from the perspective of how others (read: heterosexual men) see women. The THINX ads address how women see and take care of themselves…THINX’s ads are only shocking because they call a period what it is: “the shedding of the uterine lining” of “any menstruating human.”

But the visibility of such a commentary regarding “calling a period what it is” is something that Jess Joho calls the last taboo, and she specifically extends this line of thinking to the world of video games in an article entitled “The Blood You’ll Never See in a Game.” Joho, like Gandhi, works to understand why menstruation has been constructed as being so taboo: “But why? The source of all this long-lasting disgust and shame is, after all, just an involuntary biological function indicating sexual maturity, experienced regularly by half the population…Yet after sixty years of modern feminism, mentions of periods in mass media seem still confined to PMS as a punch line or as a source of female shame and male disgust.” And in order to interrogate both the “notable exceptions to the menstrual taboo in popular media” as well as “the awkward silences,” Joho puts Carrie in conversation with Bioshock Infinite, arguing that both “Carrie and Bioshock join a long tradition of a menstrual taboo that speaks volumes about how our society manages female power and autonomy.” But Joho also makes sure to point out that the medium of video games “isn’t particularly awash with mentions of the unmentionable.”

But the visibility of such a commentary regarding “calling a period what it is” is something that Jess Joho calls the last taboo, and she specifically extends this line of thinking to the world of video games in an article entitled “The Blood You’ll Never See in a Game.” Joho, like Gandhi, works to understand why menstruation has been constructed as being so taboo: “But why? The source of all this long-lasting disgust and shame is, after all, just an involuntary biological function indicating sexual maturity, experienced regularly by half the population…Yet after sixty years of modern feminism, mentions of periods in mass media seem still confined to PMS as a punch line or as a source of female shame and male disgust.” And in order to interrogate both the “notable exceptions to the menstrual taboo in popular media” as well as “the awkward silences,” Joho puts Carrie in conversation with Bioshock Infinite, arguing that both “Carrie and Bioshock join a long tradition of a menstrual taboo that speaks volumes about how our society manages female power and autonomy.” But Joho also makes sure to point out that the medium of video games “isn’t particularly awash with mentions of the unmentionable.”

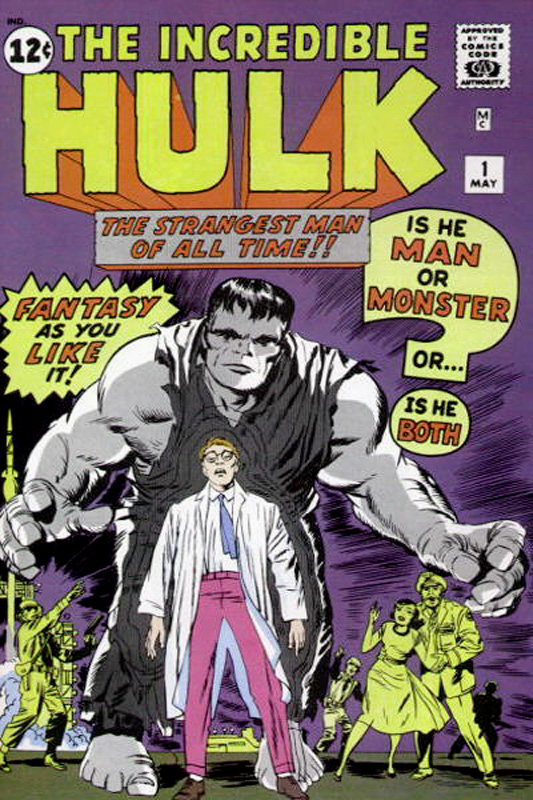

I think that Joho’s point bears repeating, for while the perpetuation of the idea of menstruation as taboo, as shameful, as unsanitary, as disgusting causes it to often be rendered invisible, when it is visible in popular media, it is often used as a signification of monstrosity for these same reasons. Indeed, Joho sheds light on this construction: “Both Carrie and Bioshock Infinite join a longstanding tradition of horrific symbolism known in psychoanalytic feminist film theory as ‘the monstrous-female.’” This idea of the monstrous-feminine is something that Barbara Creed discusses in The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, and while I’ve talked about Creed in previous posts, I think it’s important to reiterate (as Joho does as well) the fact that Creed examines the monstrous-feminine in order to highlight one of the ways that monsters “represent the uncanny and dangerous in-betweens of a society’s strictly placed boundaries: what is both human and inhuman, man and beast, male and female, girl and woman.”

And perhaps what makes menstruation—and menarche specifically—so dangerous is the manner in which it troubles the seeming boundaries between the child’s body and the maternal body, a troubling that seems to, as Joho puts it, “pose as a threat to the symbolic order of a patriarchy.” Indeed, through her discussion of Carrie and Bioshock Infinite, Joho highlights the manner in which menarche’s representation of the maternal becomes monstrously conveyed due to its challenging of the patriarchal:

The horror of Elizabeth (and Carrie) is simultaneously the magnitude of her power as well as her potential independence from the caretaking father. Symbolically, menarche represents the loss of innocence, but also a transition away from the patriarch and towards the maternal. In Infinite Elizabeth forgoes the baby doll dress for her own mother’s sexualized corset minutes after she kills Daisy and becomes a “woman.” No longer figuratively powerless, the daughter gains an ultimate ability after menarche as the potential life giver, while the father loses his role entirely. Infinite, like other media representations of menstruation, suppresses these threatening powers under the guise of patriarchal protection.

So, it seems to me that menstruation is often represented (if it is represented at all) as being dangerous and monstrous because it is bound up with the maternal body, which is also often represented as being dangerous and monstrous. And such representations bring to mind some of the questions that Soderback asks about the horror genre: “So, as women, should we feel empowered that our bodies are depicted as supernaturally dominant? That this journey through pubescence is seen as all-powerful and a force to be reckoned with? Or is it signifying of a problem when our scariest movies are about women and their bodies, placed so definitely in the category of ‘monstrous other’ that the only way to explore female puberty, menstruation, and sexuality is through fear?” When these representations are placed in conversation with other manifestations of menstruation—manifestations like the disgust aimed at Kiran Gandhi after her marathon run or like the subway’s resistance against the THINX ad campaign—it would seem to be the latter, for all these iterations reveal the hegemonic distrust and disgust felt regarding the menstruating and maternal body, a disgust that results in efforts to render such functions either invisible or monstrous, with no other options or narratives typically made available.

So, it seems to me that menstruation is often represented (if it is represented at all) as being dangerous and monstrous because it is bound up with the maternal body, which is also often represented as being dangerous and monstrous. And such representations bring to mind some of the questions that Soderback asks about the horror genre: “So, as women, should we feel empowered that our bodies are depicted as supernaturally dominant? That this journey through pubescence is seen as all-powerful and a force to be reckoned with? Or is it signifying of a problem when our scariest movies are about women and their bodies, placed so definitely in the category of ‘monstrous other’ that the only way to explore female puberty, menstruation, and sexuality is through fear?” When these representations are placed in conversation with other manifestations of menstruation—manifestations like the disgust aimed at Kiran Gandhi after her marathon run or like the subway’s resistance against the THINX ad campaign—it would seem to be the latter, for all these iterations reveal the hegemonic distrust and disgust felt regarding the menstruating and maternal body, a disgust that results in efforts to render such functions either invisible or monstrous, with no other options or narratives typically made available.