Recently, a reader approached us and asked if we could share this exclusive story detailing her experiences within the games industry. The following relates her time spent working for a major studio’s big game release. The NYMG editorial staff stands with the writer in sharing her perspective on events, and we feel it is a story that needs to be told.

What follows is our source’s version of events and experiences, presented in her own words, though certain details of the studio, the game, and the timeline have been obfuscated in the name of safety and anonymity. Please note: we are privy to details and evidence not presented here, but we will not comment on speculation or answer questions about the identity of the author or the company for which she worked. Today’s presentation is part two; you can find part one here. Be warned that part two adds discussion of suicide to the already troubling topics included in the first piece.

I learned from one of my male coworkers that a lead producer had asked several men if they wanted to livestream content I was in charge of. He never asked me. I reported the incident to HR, and they weirdly chose to side with him.

I had asked to keep my complaint anonymous, and HR’s response was to set up a meeting with him and me where he explained how he was scared for his job, how what I said had never happened, all while the HR representative nodded her head. I did not feel comfortable, or safe. I escalated the issue, and instead of admitting that she had made a mistake, I found out that she claimed I had lied and changed what the original issue was about. I told HR that I was worried about retaliation from him, and they reassured me that wouldn’t be an issue because he didn’t face any punishment for his behavior, so there was nothing to retaliate against.

One of the things I had wanted to come out from the issue was an increased focus on harassment training, for him specifically and the office in general. The system in place was a minimalist manager-only two-hour multiple-choice computer program. No one else got anything. The program dinged you if you went too fast, and, while supposedly mandatory, many leaders ducked out of it anyway. HR central promised me that they would step up on harassment training, but they put it off for months, only reviving the idea once I came to them with a second complaint. And even then, they kept the training for managers-only.

Which, certainly the managers needed it. For International Women’s Day, we had a speaker come talk to us about women in the workplace, and only a handful of people showed up, all but one of them women, and none of them in senior leadership or even design. Certainly there was no incentive for the people who needed to attend to pay any attention at all. I was disappointed at the turnout, until I heard the speaker. She told us that she hated other women, that she enjoyed working with men because they would do things for her. I asked her her opinions on getting men more involved (gesturing to the poor turnout), and she recommended telling men that they should care about improving their dating pool. The blowback from those that attended was pretty justified. I’d hoped they would fix the problem, but next year they just didn’t do anything at all for Women’s Day.

And really, even the company’s charitable ventures were focused on throwing money at the problem without actually working on concrete solutions. The company sponsored our appearance in a local gay pride parade, but the organizers accommodated people who requested not to receive updates about the parade by creating a separate listserv, instead of calling anyone out for homophobia. The company sponsors youth initiatives to get girls into gaming, but with a volunteer roster, it’s a way to look good without actually pushing any of the employees to fix the pipeline problem of women wanting out once they get in. One of their more ridiculous charity campaigns was asking for donations of women’s business suits and makeup in an industry where men get to wear gaming T-shirts, jeans, and Hawaiian shirts.

I felt like it was important to actively encourage internal change, to hold designers accountable to improving, so I requested a platform to discuss more equitable game design better strategies. It was granted, but then I was unceremoniously bumped for an announcement about a new project, and the chance was never given again. My subsequent emails asking about it were never answered.

Looking back at the worst of it, I feel lucky, lucky in the same sense that I suffered “only” a general malaise instead of sharp, vicious incidents. Although, it might have been better to have suffered sharp incidents instead of the constant, dragging misery that they cultivated.

I was told that I’d get ahead in the company by sleeping my way to the top, and it turned out that rejecting at least one advance definitely affected my ability to get ahead. Additionally, I had to deal with receiving inappropriate comments, and, afraid of being flagged as unprofessional, I silently dealt with the fact that an ex-boyfriend working in the same office told me he counted how many times a day he passed my desk without me seeing him. In the end, I felt lucky that I didn’t have to deal with inappropriate touching or overt demands.

I was told that I’d get ahead in the company by sleeping my way to the top, and it turned out that rejecting at least one advance definitely affected my ability to get ahead. Additionally, I had to deal with receiving inappropriate comments, and, afraid of being flagged as unprofessional, I silently dealt with the fact that an ex-boyfriend working in the same office told me he counted how many times a day he passed my desk without me seeing him. In the end, I felt lucky that I didn’t have to deal with inappropriate touching or overt demands.

Knowing that other people were suffering, sometimes worse than me, made it feel like calling things out, and holding the staff accountable, was especially important. Many of my coworkers didn’t feel comfortable bringing up their issues to HR, let alone escalating the issue once the initial gauntlet went wonky. I don’t blame them. Every time I went to HR, I had to deal with another instance of not being taken seriously, or not being understood. I seriously got yelled at when I explained that referring to trans people as “transgenders” was analogous to calling people “blacks.” I had to explain what “streaming” meant to several people in HR, and even what Gamergate was to someone from corporate. It was so bizarre dealing with so many HR people in a gaming company who knew nothing about gaming, and little about how to create or encourage a safe space.

They were very adept at creating silence, though. When enough incidents accrued that I decided to quit, they asked me to file a formal complaint first. It was pretty clearly a tactic to give them plausible deniability that they had tried their best to fix my issues before I quit. During the investigation, I was put on administrative leave with my email cut off. For my safety. They didn’t do this to the person I complained about.

Their decision was that my complaints had no basis, that no actions would be taken, and that I had a week left. What they didn’t also tell me is that with the investigation over, I still wouldn’t be allowed to use my work email: not to get documentation, not to pass on my LinkedIn, not to say goodbye to my coworkers. They gave different stories about why this was happening: before, my email had been turned off to protect me from harassment, but now it was just too much hassle for IT to turn my access back on. Also, employees weren’t allowed to send out goodbye emails anyway. But the real reason was obvious: it was another way to ensure my silence, to make sure that I didn’t warn anyone else what had happened and how it might happen to them too.

Out of respect for my coworkers, I won’t discuss their issues, with one exception. A trans woman was struggling working there, and never felt comfortable. She confided in me that she hated it there, that she was going to quit, that she had to do so for her own health, even though it put some of her transition surgeries in danger. She understandably didn’t want to deal with going to HR to report those issues, as she was dealing with enough on her own. So I went to HR, I pushed back. Not on her behalf, or anyone else’s, but because someone needed to, for her and others like her. When HR told me that my complaints had no basis and nothing would happen, I cried. I cried because I knew that nothing would change for me, but I also knew that nothing would change for women like her.

Out of respect for my coworkers, I won’t discuss their issues, with one exception. A trans woman was struggling working there, and never felt comfortable. She confided in me that she hated it there, that she was going to quit, that she had to do so for her own health, even though it put some of her transition surgeries in danger. She understandably didn’t want to deal with going to HR to report those issues, as she was dealing with enough on her own. So I went to HR, I pushed back. Not on her behalf, or anyone else’s, but because someone needed to, for her and others like her. When HR told me that my complaints had no basis and nothing would happen, I cried. I cried because I knew that nothing would change for me, but I also knew that nothing would change for women like her.

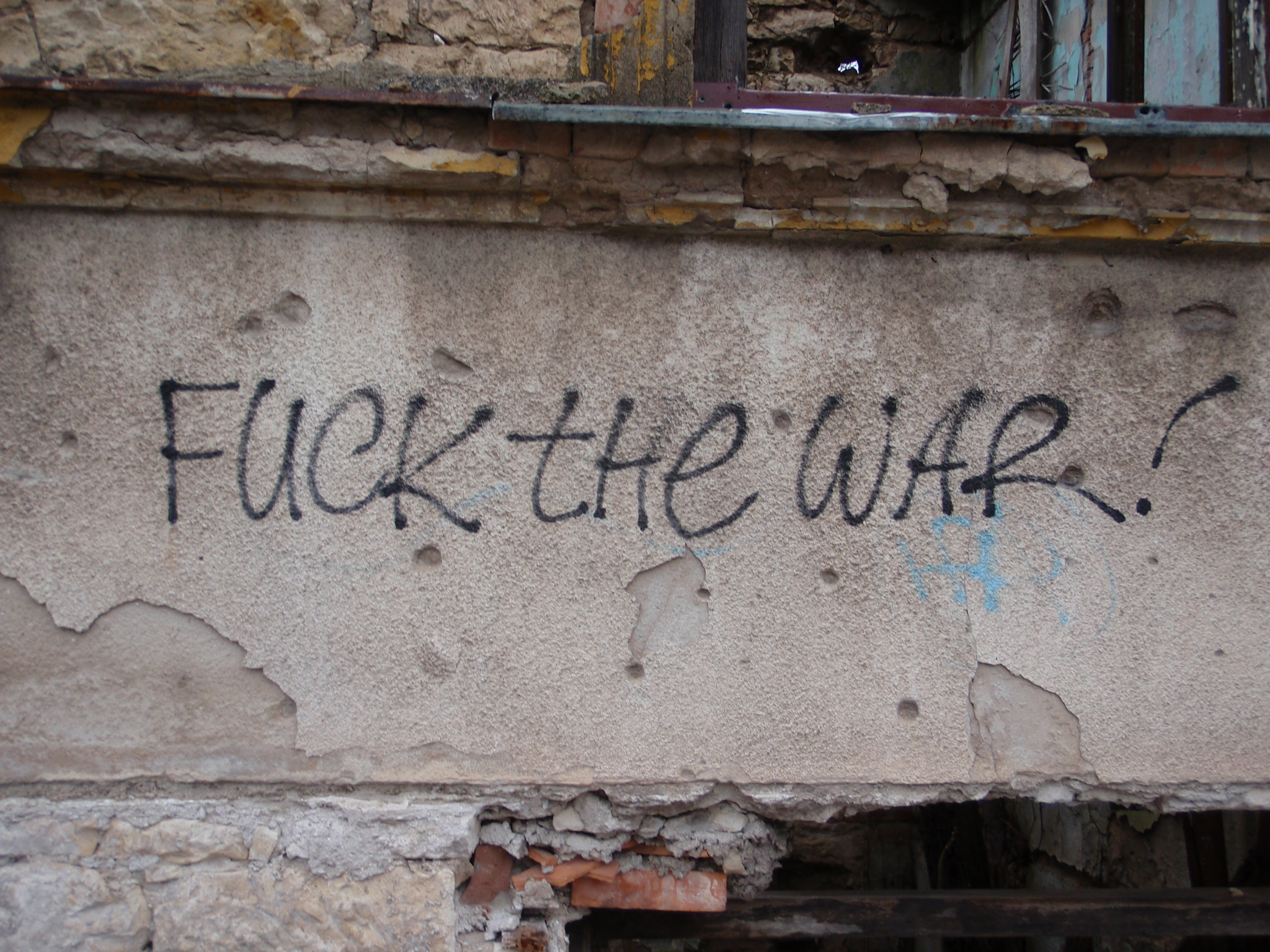

Not long after she finally quit, she took her own life. She had her own private issues, but not having a safe place to work was a huge issue. She had quit the company before because she felt so uncomfortable working there. Looking back, I wonder if she could have still been alive if the company had actually been supportive of her.

What would it have meant to her if the designers had been willing to introduce a trans character when I asked for it? If NPCs having the wrong gender voice had been a feature, not a bug? I know she hated her voice. How might it have been different if deadnaming and misgendering a fellow employee was something that got you a quiet word instead of an unquestioned promotion? If maybe the company hadn’t thought that one of the ways they could support women was to give them pretty clothes and makeup, to make them look more feminine? Instead, when I looked back over everything, to memorialize her, I noticed that several of the credits actually deadnamed her. It felt very symbolic of the company’s priorities.

I hate the fact that the company failed her so miserably when they had a chance to really self-examine and improve their situation. And really, that’s all it would have taken: apologizing, improving, moving on. Working with people asking for change instead of resisting against them. I hate having had to leave, because there were some amazing, smart, funny, creative people there, and a lot of the work was rewarding and fun. But working in that place, I was starting to feel like she had. It wasn’t healthy or safe. I hope that they’ll take the time to really work towards better solutions, towards creating a better environment, but I’m worried by the fact that it’s just not going to happen. At least, not without some massive lawsuit.

One thought on “One Voice in the Dark: Sexism and Hostile Workspaces in the Games Industry (Part Two)”

Thanks again for telling your story.