Warning: MGSV spoilers, discussions of sexual violence and war within.

Metal Gear is and has always been a weird beast. Sometimes the good guys are bad guys are good guys on the side and sometimes they’re all clones and have maybe exchanged a body part or two. In this universe, Sons of Liberty and Snake Eater and Guns of the Patriots all exist with straight faces and also there are some retcons and sometimes the bad guys look right at you and talk to you about your gaming habits. It’s just Metal Gear; that’s how it is. Breaking the fourth wall. The latest installment, The Phantom Pain, hangs (partially; Metal Gear never does one thing) on references to Moby Dick (including a giant flaming whale because why not, because Metal Gear). It’s a game about seeing and later understanding and seeing again and maybe not quite understanding, because you’re too busy shaping the world around your own perceptions. I’ve been playing it, and while I’m not done, I’ve seen the whole of the plot, know the twists and curves of story, which gave me quite the perspective (something I’ll go into at a later date, I expect).

I played the old Metal Gear games. I never played the portables, or finished Guns of the Patriots, and I don’t know if I’ll finish this one any time soon, because classes are starting again and free time comes at a premium. Free time because while this is my work, playing and thinking, I don’t know if Metal Gear is, because that’s someone’s life work, and I don’t think that someone is me.

I never planned to play MGSV; like Ground Zeroes, I had chosen to avoid this installment. In fact, I thought I was done with Metal Gear. I didn’t play Ground Zeroes because I read about the elements of sexual violence and I didn’t want to experience that. I’m not saying it shouldn’t be in the game; I’m just saying I chose not to play. Sexual violence plays an important role in Ground Zeroes, and here, too; I’d seen those scenes, and the horrific realism of some of the deaths in this game. I didn’t want any part of it.

But the corrupting influence of a friend overrode my initial plans, and because the game is good, great (sometimes, because Metal Gear is never one thing, remember), and here I am, running around Africa and Afghanistan, stealing everything that isn’t rooted in the ground, listening to a-Ha and Hall & Oates, changing the lyrics of “Maneater” to “Manbeater” when I run around my pink Mother Base, smacking my soldiers around because that’s what one does (or can do) while home on the base, to improve morale. “Thanks for that, Boss,” they say, breathless. “The man who stole the world,” I sing, attaching balloons to freight containers and watching them sail off into the sky. I spend five minutes lying in the shadow of rocks, scanning, watching, thinking, figuring out where to go, chewing my lip, sipping a beer, thinking about which guy to tag first, second, third, how to take the outpost without raising an alarm, how to steal all the things. That’s pure, for me; in games, I steal. I hoard. As I type this, I have some sixty thousand fuel resources I really wish my base dev team would get around to processing. With Quiet and the knife-wielding DD, I’ve taken it all. I’ll tranq these guys and take them, too, even though I don’t need them. My base overfloweth.

But the corrupting influence of a friend overrode my initial plans, and because the game is good, great (sometimes, because Metal Gear is never one thing, remember), and here I am, running around Africa and Afghanistan, stealing everything that isn’t rooted in the ground, listening to a-Ha and Hall & Oates, changing the lyrics of “Maneater” to “Manbeater” when I run around my pink Mother Base, smacking my soldiers around because that’s what one does (or can do) while home on the base, to improve morale. “Thanks for that, Boss,” they say, breathless. “The man who stole the world,” I sing, attaching balloons to freight containers and watching them sail off into the sky. I spend five minutes lying in the shadow of rocks, scanning, watching, thinking, figuring out where to go, chewing my lip, sipping a beer, thinking about which guy to tag first, second, third, how to take the outpost without raising an alarm, how to steal all the things. That’s pure, for me; in games, I steal. I hoard. As I type this, I have some sixty thousand fuel resources I really wish my base dev team would get around to processing. With Quiet and the knife-wielding DD, I’ve taken it all. I’ll tranq these guys and take them, too, even though I don’t need them. My base overfloweth.

I have trouble being the bad guy in games. When I went for my second round of Mass Effect, I set out to do things differently, to be a little more villainous, to have less patience, to use violence to solve problems, but a few hours in, I found I was essentially replicating my first game, in which my Shepard had been the Paragon of paragons. In Fallout games, in the Elder Scrolls, it’s all the same: I don’t kill when I don’t have to. I don’t kill for convenience. I save people, and it hurts when I fail. When I can’t be the hero. I’m a white hat to the core; even the stealing, I tell myself, is a bit of a Robin Hood thing. I’ll steal these things and help the poor (through quests!).

I don’t know who the good guys are here in The Phantom Pain. Ocelot is Ocelot and not to be trusted — dude’s got more layers and versions than a soap opera villain with a secret twin or six — though he’s my favorite character here (except maybe for my dog). I despise Kaz and often yell back at the screen when he’s talking, but he’s probably the closest thing to a good guy on Mother Base. As much as I hate him (and I’ll hate him more, knowing what’s coming later in the game), he’s straightforward; in a game of layers and curves and switches, Kaz is the embodiment of the title, the living remnant, bent toward a better world (sort of) and revenge on those who’ve wronged us, and maybe some torture along the way.

He’s not a good guy. I hate him.

Metal Gear is usually, but not always, a game dedicated to not using weapons in a world full of weapons, massive weapons, epic weapons, customizable weapons. In The Phantom Pain, you can attach weapons to weapons; you can steal weapons; you can blow shit up in maddening and glorious ways. But sneaking and disdaining the kill still nets special bonuses, because stealth is the order of the day. Sneak, while hauling a sniper rifle as long as your own body. Sure.

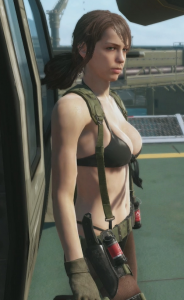

Ultimately, I’m not a good guy, not even when I look for ways to avoid killing. I’m still not good. I sneak when I can; I avoid the weapons hanging off my body and I think about the implications of war and the pits that have been dug for prisoners in camps and the fact that I’m running through exploited lands in Africa, and I steal. I kill and I steal, and I’m a fake. I’m a liar. I slap the men around on Mother Base. There are only four women; I slap them, too, except for Quiet, who suns herself in a cell, breathing.

Ultimately, I’m not a good guy, not even when I look for ways to avoid killing. I’m still not good. I sneak when I can; I avoid the weapons hanging off my body and I think about the implications of war and the pits that have been dug for prisoners in camps and the fact that I’m running through exploited lands in Africa, and I steal. I kill and I steal, and I’m a fake. I’m a liar. I slap the men around on Mother Base. There are only four women; I slap them, too, except for Quiet, who suns herself in a cell, breathing.

I dropped supplies on her head to beat her.

It’s difficult for me to reconcile The Phantom Pain with itself. There are children in cages clutching handfuls of diamonds I must save, my dog has a knife and flips around when he uses it, and there’s also Quiet. My son, who is not supposed to be around this game, nevertheless walked into the room during a scene in which Quiet was described as “well-suited” for a mission. He was behind me and I didn’t know he was there until he started cackling. “Well-suited! For what? She’s not even dressed!”

He thought it was hilarious. He’s seven. Even he knows Quiet is ridiculous, a stretch far out into the distance even for Metal Gear. My friend who dragged me into this confessed he didn’t use her as a buddy. “I can’t take her seriously,” he said, or maybe he said he couldn’t take himself seriously with her. But hey, she’s a solid companion, and there’s a hornlike piece of shrapnel sticking out of my head, so what’s serious?

Some of the scenes I wanted to avoid in Ground Zeroes were repeated here, in flashback. I didn’t want to see; I had to see. Thanks for that, Kojima. Around the corner, some time in the future, a soldier will stand over Quiet and unzip his pants. Maybe I will get there. Maybe I will turn away.

The game begins in a hospital. You are a patient, groggy, wrapped in bandages; everything is blurred and hazy. The first thing that comes into sharp relief, into focus, is a nurse’s breasts. In scenes I have watched, but have not yet reached in missions, Quiet is tortured, and the camera lingers on her breasts. Maybe I will remind myself that I hate her humming, and that will help me sit through those scenes, but probably not, because humming in an annoying way does not mean someone deserves torture. I will yell at Kaz for being Kaz. I will sigh at the end, which is a little melodramatic, but I will think, too, about agency, and whether Quiet has it. She chooses part of her path, with what freedom she has, but she’s also wholly crafted, designed — which makes me think, do characters have agency? Does Venom Snake have agency here? Kaz? We can’t look away sometimes. We see only what the camera wants us to see.

Can characters have agency? I don’t know; that’s a deeper question than I’m prepared to answer here, but they can be created in such a way that the story moves with and around or because of their perceived agency. Ahab is created but it’s his story-actions that doom his crew. His agency, or what we see as his agency.

Venom Snake is Ahab. There are implications there that never seem to match the Big Boss in my game, the one lying in the grass in battle dress, the one picking flowers and sending everything back home via balloon, the one who saves children and parasitic snipers. There is another man, called Ishmael, but is he?

Maybe it all depends on whose story it is. Maybe if Ahab had been the narrator of Moby Dick, we’d have had a different perspective; maybe Venom Snake’s story isn’t really a Metal Gear story at all. It’s all about what we see and what we don’t, and about perspective. If I hadn’t known the story beforehand, I might never have picked it up, despite my love for crawling across landscapes, because I would have assumed it was too much. Knowing the story as I do, it still may be. I don’t know how long I’ll go. Watching and doing are different things; now I’ll have agency, but only some. I can’t click away; I can only sit through cut scenes and think on the horrors of war, which Metal Gear is doing very well in this installment, sometimes. Sometimes you get the “wahoo!” of a prisoner being balloon-lifted out of the hot zone, sometimes Ocelot jangles his spurs while he tells the men on Mother Base to forget about Hollywood, and sometimes there are children with rifles. It’s all Metal Gear — and decades ago, in the first game, Big Boss told the player to abort the mission by turning off the game, and that, I think, is worth remembering.

One thought on “In the Midnight Hour, More Metal Gear”

Great article!