Recently, as I re-read Raph Koster’s A Theory of Fun for Game Design, I kept thinking about the differences between the games Koster was using as examples and the games I’ve most often been writing about lately, the indies and the so-called walking simulators, games that often have low levels of what we would traditionally think of as game mechanics, games that are interactive in unconventional ways.

Recently, as I re-read Raph Koster’s A Theory of Fun for Game Design, I kept thinking about the differences between the games Koster was using as examples and the games I’ve most often been writing about lately, the indies and the so-called walking simulators, games that often have low levels of what we would traditionally think of as game mechanics, games that are interactive in unconventional ways.

Often, when people talk about walking simulators, they’re talking about largely story-driven games, games about discovery, games that might be written off by some as not games at all due to lack of combat or other more traditional game system mechanics. Walking simulators are, by and large, about existing in the game space, and what happens while existing. Gone Home is a frequent mention when walking simulators come up, because in Gone Home the player walks around, finds items, looks at them, and pieces together a story. The only real interaction or game-movement is moving, hence the reference as a walking simulator. The phrase, however, is often used in a derogatory fashion, as a more recent take on the gatekeeping discussions of what is and isn’t a game (and thus, who is and isn’t a gamer). What’s the point of a walking simulator, detractors huff. All you do is move around.

But Gone Home, like many games categorized as walking simulators, offers something that can’t really be achieved in other forms of media. Here, it’s the experience of discovering your family’s emotional turmoil during a year-long absence, and further, it’s a strong metaphor for being outside an emotional experience of becoming that can be difficult to understand for someone who hasn’t been through it. As with stories, the player (reader) can find cognates with the foreign experience within their own experiences, but an interactive experience does this in a different way than does a book or story. Submerged is perhaps another strong example here, considering the game has no fail state, and consists mostly of going from this point to that via boat. It isn’t really a challenge, and you can’t lose, so what’s the point? Why have an interactive experience at all? Why not a movie, or a book?

I think these are questions worth asking, but to explore them in Koster’s terms, we should look at the sections of the book itself that stirred these questions in my mind. First, in chapter three, Koster begins discussing his ideas of what games are — in fact, that’s the chapter title. He begins by talking about learning as central to games, and pattern recognition as well; as players, we are presented with challenges in games, and we must master the skills/patterns required to surpass those challenges, and we’ll only play as long as there is a challenge, usually. Boredom kills our desire to play, but that boredom can take many forms. Here are a few of those forms, in terms of learning/skills/challenges, that Koster lays out:

-The player might grok how the game works from just the first five minutes, and then the game will be dismissed as trivial, just as an adult dismisses tic-tac-toe. This doesn’t mean the player actually solved the game; she may have just arrived at a good-enough strategy or heuristic that lets her get by. “Too easy,” might be the remark the player makes.

-The player might grok that there’s a ton of depth to the possible permutations in a game, but conclude that these permutations are below their level of interest—sort of like saying, “Yeah, there’s a ton of depth in baseball, but memorizing the RBI stats for the past 20 years is not all that useful to me.”

-The player might fail to see any patterns whatsoever, and nothing is more boring than noise. “This is too hard.”

-The game might unveil new variations in the pattern too slowly, in which case the game may be dismissed as trivial too early, even though it does have depth. “The difficulty ramps too slowly.”

-The game might also unveil the variations too quickly, which then leads to players losing control of the pattern and giving up because it looks like noise again. “This got too hard too fast,” they’ll say.

-The player might master everything in the pattern. He has exhausted the fun, consumed it all. “I beat it.” (Chapter 3)

Koster then says, “The definition of a good game is therefore ‘one that teaches everything it has to offer before the player stops playing.'” This, of course, is subjective, not only because we’re talking about goodness, but because we’re talking about what a game can offer to any given player. That’s a big statement. While the bulleted list above encompasses many of the reasons we might stop playing a game, I’m not sure we can create such a simple list about what goodness or what a game can offer, which may be why Koster doesn’t. Instead, in chapter four, he moves on to discussing the kinds of things games can teach us.

I particularly like this section, because of that fascination with patterns he mentions; I like to break things down, and to categorize them (which is probably at the base of my fascination with such outliers as The Beginner’s Guide and Submerged). Koster talks about many games as reinforcing survival skills we may no longer really need — hunting, aiming, timing, projecting power, etc. But beyond these broad categories, Koster offers up some very specific breakdowns of a particular category — platformers — in order to explore how that style of game has changed from early to contemporary models (spoiler: not a lot). He breaks them down as “get to the other side” games and “visit all the locations” games.

Looking at this, I have a hard time then seeing how walking simulators can be argued as not fitting into the categories of games. Gone Home is a “find all the things” game, while a game like Depression Quest is a “get to the other side” (of depression, sorta). The methods and purpose aren’t the same as in the games Koster uses as examples, like Frogger and Pac-Man, games in which one often collects or moves simply for the sake of collecting/moving (get the power-ups, match the timing, get the skills, succeed, celebrate). This is what we often think of when we think of play. We think fetch quests (get all the things) or boss fights (a very complicated “get to the other side”). But bring in Koster’s insistence that patterns and learning are at the center of games and fun, and I think we can look at so-called walking simulators in a very different way. There are patterns to learn, but they are simply different. In Gone Home, the player reveals story, and drive and interest may reveal more story to one player than to another, thus creating a different understanding. In Depression Quest, the player learns the various patterns of actions while observing what roads are open and closed at any given time, and must use that information to navigate the situation.

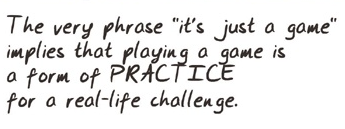

These aren’t difficult patterns, though, not in terms of mechanics. There’s no no bruise-your-fingers, throw-your-controller, Ultimecia-in-Final-Fantasy–VIII kind of thing going on here. But there are patterns, and more, there’s something else Koster says players gain from games: practice, simple practice. Maybe that’s practice aiming, hunting, etc. But can it not also be the practice of empathy?

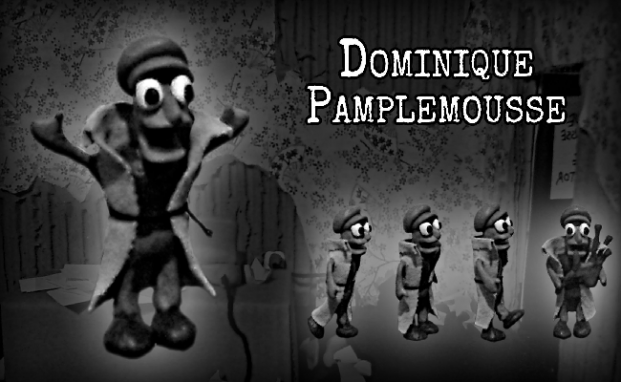

I think this can take many forms in the kinds of games I’m talking about. Sometimes it’s very direct, as with Gone Home, Depression Quest, or 12hrs. Sometimes it’s part of the story, as with Submerged, but the patterns are also forefront, as I think Submerged is a game and not a film or story because of the visceral quality of experiencing that particular story, as well as piecing everything slowly together in a story without dialogue or any real text at all, but simply visual clues and pictograms. The patterns are important, and reveal more than the actual play does, but they’re also tied inextricably to a highly emotional experience. In The Beginner’s Guide, too, a game I struggled with calling a game at all for a time, players must piece together information, determining what’s true and what’s not, in order to get into the mental state of the creator. We put clues together in order to understand.

I think this can take many forms in the kinds of games I’m talking about. Sometimes it’s very direct, as with Gone Home, Depression Quest, or 12hrs. Sometimes it’s part of the story, as with Submerged, but the patterns are also forefront, as I think Submerged is a game and not a film or story because of the visceral quality of experiencing that particular story, as well as piecing everything slowly together in a story without dialogue or any real text at all, but simply visual clues and pictograms. The patterns are important, and reveal more than the actual play does, but they’re also tied inextricably to a highly emotional experience. In The Beginner’s Guide, too, a game I struggled with calling a game at all for a time, players must piece together information, determining what’s true and what’s not, in order to get into the mental state of the creator. We put clues together in order to understand.

Games can accomplish this in more “traditional” forms, too; The Last of Us is often categorized as highly emotional, and moving from The Last of Us to Submerged would produce a wildly varied spectrum of games in between, but at the heart, I think the purpose and play are in some ways very similar. In both games, the player is thrust into a parental role and must help someone weaker survive a post-apocalyptic world. This is accomplished by visiting all the places and finding all the relevant things. It’s just that in one game, the player probably dies many times and struggles to pass enemies, while in the other, there is only the occasional struggle to find the right path, and to piece information together. In reviewing Gone Home for Bloody Disgusting, Adam Dodd made a similar connection with Bioshock, for instance. The only real difference is that no one would doubt the “gameness” of Bioshock or The Last of Us, walking simulators are often decried as not-games. As I said above, I’ve fallen prey to it myself, even, from time to time, before deciding to stop working with rigid criteria of what games are and to instead think of the form as evolving and growing its potential — which benefits us all, doesn’t it?

I’d certainly argue that empathy and understanding are important life skills, but presenting them this way in a game may invoke some of Koster’s characteristics of boredom for some players. Maybe the players reject interactive stories for their own sake, preferring other forms of skill-reinforcement. Maybe they see the pattern but just don’t find it useful. Maybe they prefer something with a staggered challenge. That’s fine; there are plenty of games on the shelf. But the use of the label “walking simulator” to disparage something that one simply isn’t interested in, and the accusation of not-game to undermine someone else’s interests doesn’t seem to bear out when design characteristics of these games are considered. They are games. Whether or not they’re good is up to individual players, same as with anything else.

One thought on “Walking Simulators and the Theory of Fun”

I very much agree with your entire analysis! The typical “walking simulator” (wish we had a better term) IS a game in the formal sense, in my mind.

I have actually made the exact same case myself before, though not as succinctly. I see “walking simulators” as indeed games of piecing together bits of narrative into a coherent whole in the mind of the user, which includes quite a lot of pattern matching, as you state.

The hidden gotcha in my definition of a “good game” is that it’s going to be different for everyone. Walking sims aren’t for everyone, but no game is.

This is also the hidden gotcha in my discussion of patterns… you can find them all over the place, and not just in designed games.

There are games (in the casual sense) that I don’t think are games (in the formal sense), and I tend to call them “liminal” because they exist in the fuzzy areas at the edges (there aren’t categories, after all, but more like… clusters?). A lot of work in Twine, for example, is easier to think about through the lens of hypertext than from a ludology perspective… but then again, under a strict formal lens, adventure games are actually puzzle collections more than games, and nobody is looking to lock them out. Formal lenses are only useful insofar as they are helpful and illuinate things.