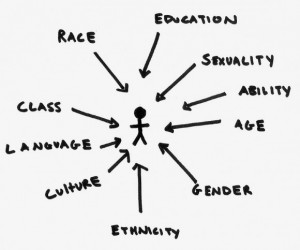

I’ve been thinking a lot about my transition to Games Studies this last semester and the role it plays (and will play) in my research as a Second Language Studies student; I’ve also been pondering on the role of intersectionality lately, specifically how Latoya Peterson admonishes in her article, Intersectionality is Not a Label, that intersectionality is a framework for understanding how a variety (or diverse set) of oppressions can intersect, and yet the term has lost its political flair as it’s become more about belonging than rallying to action, and the mirroring of this lack of critical engagement in my very globalized field, which is ultimately how I ended up in this community – seeking out critical inquiry as it pertains to the roles of language learning (and academia in general) at predominately white institutions that push upon Others the normative conceptions of what is and what is not acceptable socially, linguistically, academically, communally. Reflecting on course readings I’ve been digging into so far this semester, specifically Miguel Sicart’s Beyond Choices: The Design of Ethical Gameplay, I’ve come to a sort of collision point with my previous conceptions of the role of games in everyday life and in the classroom and the endless possibilities at my fingertips. This idea that games highlight personal principles and open a discussion that can be longstanding is nothing short of what I hope to bring about in the community of my classroom(s) – why do we make certain (rhetorical) choices we and how do games reflect our ethical positions and the ethical position of societies we often happen upon as outsiders, as sojourners? What are our narratives and how do we reconcile ours within places whose narratives lay upon our shoulders the cloak of Otherness, the cloak of exile? These are the questions I attempt to unpack with my ESL, and mainstream, composition classrooms.

framework for understanding how a variety (or diverse set) of oppressions can intersect, and yet the term has lost its political flair as it’s become more about belonging than rallying to action, and the mirroring of this lack of critical engagement in my very globalized field, which is ultimately how I ended up in this community – seeking out critical inquiry as it pertains to the roles of language learning (and academia in general) at predominately white institutions that push upon Others the normative conceptions of what is and what is not acceptable socially, linguistically, academically, communally. Reflecting on course readings I’ve been digging into so far this semester, specifically Miguel Sicart’s Beyond Choices: The Design of Ethical Gameplay, I’ve come to a sort of collision point with my previous conceptions of the role of games in everyday life and in the classroom and the endless possibilities at my fingertips. This idea that games highlight personal principles and open a discussion that can be longstanding is nothing short of what I hope to bring about in the community of my classroom(s) – why do we make certain (rhetorical) choices we and how do games reflect our ethical positions and the ethical position of societies we often happen upon as outsiders, as sojourners? What are our narratives and how do we reconcile ours within places whose narratives lay upon our shoulders the cloak of Otherness, the cloak of exile? These are the questions I attempt to unpack with my ESL, and mainstream, composition classrooms.

The games I’ve been playing lately offer choices I don’t readily see as reflective of my non-gaming person; but they are. For example, upon playing the game Destiny: The Taken King, my first experience with it was the primary choice I’m offered in character creation. Not having played a game before that allowed me the ability to somewhat fashion an avatar to somewhat resemble me, I was thrilled. I had choices of being. I had choices. That is, until I sit down in the game and then I’m forced to sit like a “lady”; no choice there. It is this idea of choice which I believe has been an undercurrent in my previous posts on body diversity – diversity opens the door to choice, to representation, to identification. Interestingly enough, it wasn’t until I was engaged in a conversation with another professor (in a different department of course), whose scholarship unravels the complexity of educational policy in the k-12 context from a critical perspective, that gender is often the tidal wave I’m able to stay above, I’m able to glide and negotiate and ultimately facilitate fruitful conversations with my community-based classrooms in a no-nonsense manner; race, however, is that undercurrent that grips my ankles and every so often drags me under. The micro-aggressions are always more challenging than the macro. So, if intersectionality remains a term, label, by which people attempt to belong to rather than engage with critically, I imagine these micro-aggressions prevailing; especially when games continue to reflect the undercurrents of society in the game choices, or lack thereof.

the primary choice I’m offered in character creation. Not having played a game before that allowed me the ability to somewhat fashion an avatar to somewhat resemble me, I was thrilled. I had choices of being. I had choices. That is, until I sit down in the game and then I’m forced to sit like a “lady”; no choice there. It is this idea of choice which I believe has been an undercurrent in my previous posts on body diversity – diversity opens the door to choice, to representation, to identification. Interestingly enough, it wasn’t until I was engaged in a conversation with another professor (in a different department of course), whose scholarship unravels the complexity of educational policy in the k-12 context from a critical perspective, that gender is often the tidal wave I’m able to stay above, I’m able to glide and negotiate and ultimately facilitate fruitful conversations with my community-based classrooms in a no-nonsense manner; race, however, is that undercurrent that grips my ankles and every so often drags me under. The micro-aggressions are always more challenging than the macro. So, if intersectionality remains a term, label, by which people attempt to belong to rather than engage with critically, I imagine these micro-aggressions prevailing; especially when games continue to reflect the undercurrents of society in the game choices, or lack thereof.

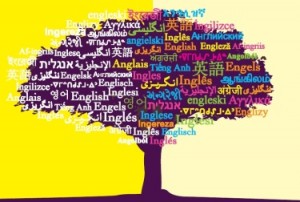

Picking a game for the classroom then, specifically in the ESL context, that allows this discussion of tidal waves and undercurrents to emerge organically is certainly challenging; what I’ve discovered at my stage of playing is that the games with the least dialogue produce the greatest narrative effect. Perhaps this is due to the reduced risk of language barriers, the ability to draw on one’s own understanding of cultural concepts without the direct input from a different language (which implies a different culture as well); this lack of dialogue creates an inclusive play experience where the cultur e of the game and the culture of the player may intersect. As the game design allows the player to construct words to the narrative being played out, a greater impact on my understanding of my own positionality and that others takes place; specifically thinking about these terms diversity, intersectionality, and ethics. One such game that I’ve fallen in love with is A Bird Story – I recently wrote about how A Bird Story managed to calm a tyrannical two-year old and soften the creases of his resistance. As I, by myself, continued to play the game, I noticed more of the intricate details that the designers constructed. For example, the only characters in the game with any semblance of a race, gender, ethnicity, or being are the main character and the bird – all other additional characters are shadows of beings. For instance, the veterinarian is dressed in a white coat, and there are features that cause me to imagine this shadowy, white-coated figure as a woman, but I’ve no idea her race, or if she is a she and not he. Even the other birds in the stories are shadows. While you can kind of imagine the origins of the young boy based on his physical features, you’re not 100% certain and the narrative is constructed in such a way that, maybe, races are inclusive, that, maybe, the story bridges belonging and intersectionality as the player is absorbed into this child’s, seemingly, isolated life with only the companionship of a wounded bird.

e of the game and the culture of the player may intersect. As the game design allows the player to construct words to the narrative being played out, a greater impact on my understanding of my own positionality and that others takes place; specifically thinking about these terms diversity, intersectionality, and ethics. One such game that I’ve fallen in love with is A Bird Story – I recently wrote about how A Bird Story managed to calm a tyrannical two-year old and soften the creases of his resistance. As I, by myself, continued to play the game, I noticed more of the intricate details that the designers constructed. For example, the only characters in the game with any semblance of a race, gender, ethnicity, or being are the main character and the bird – all other additional characters are shadows of beings. For instance, the veterinarian is dressed in a white coat, and there are features that cause me to imagine this shadowy, white-coated figure as a woman, but I’ve no idea her race, or if she is a she and not he. Even the other birds in the stories are shadows. While you can kind of imagine the origins of the young boy based on his physical features, you’re not 100% certain and the narrative is constructed in such a way that, maybe, races are inclusive, that, maybe, the story bridges belonging and intersectionality as the player is absorbed into this child’s, seemingly, isolated life with only the companionship of a wounded bird.

Because my students just started playing the game and I’ve no report on their first impressions and what they’ve noticed and engaged with, I can’t say for sure that my hopes and dreams won’t be deferred. What I can say is: I’m excited and I’m anticipating the possibility of critical perspectives through engagement with games in my classroom, and in my field – even if it’s only within my little corner. Someday, I will build a bridge or two.