As promised, my ESL composition class played A Bird Story and it’s been a wonderful and insightful experience reading their reactions to a game they’ve deemed as unworthy of “gaming” status (I’ll touch on this a bit below); they didn’t anticipate that I would, however, expect this reaction from them regarding a narrative based game where choices are limited for the player. Many made arguments that a primary requirement for a game to be a game was the connection it builds with the player through the use of controls and mechanics. Naturally, I challenged them with a bit of Sicart in our discussion on game design. They will continue to read his glorious ideas and will become convinced, as I have, of the intricate role emotions and ethics play in gaming…

but first…

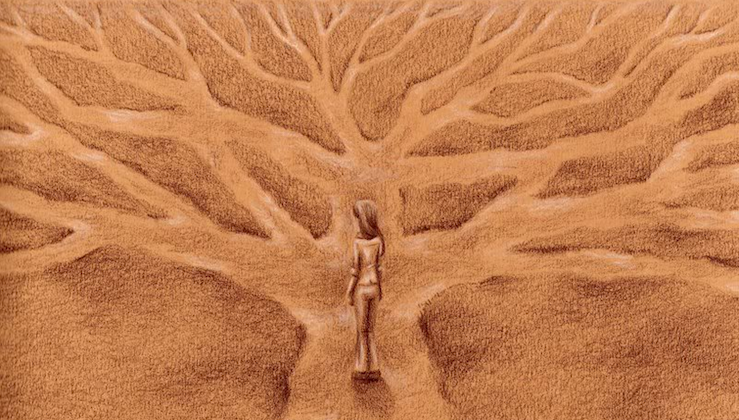

While some of my shy, but thought-provoking, students stood on their soapbox and exclaimed that A Bird Story failed to meet their expectations of a game with the lack of interaction (that they loosely defined) between the game and their physical bodies, omission of dialogue, mediocre design (I obviously disagree here as I adore the graphics) and unclear boundaries between reality, dream, and imagination, others found meanings I kicked myself for not seeing. For example, one element of design I’ve mentioned earlier is the game creators’ decision to make all the other characters, aside from the nameless child and wounded bird, mere shadows. With my mind sandwiched between Critical Race Theory and theories of Language Acquisition, I interpreted this decision as a way to bring inclusion across cultures and races and languages; while that’s not to say this wasn’t one of the intended purposes, many of my students interpreted these shadowy figures as a representation of the boy’s loneliness, his isolation – I find their perspective more beautiful than my own. Students also disagreed on the effectiveness of the soundtrack – some found it mismatched, and creepy, others found it relaxing and inviting; a few students found the game childish and meant to be a picture book for a younger audience while others maintained that children would be unable to understand the intricate details woven in through picture thought-bubbles and exclamation points, which could either mean anger, excitement, or surprise depending on the context of the scene(s). Despite all these differences, one thing we all came to agree upon after a lengthy discussion on rhetorical analysis is that the themes woven throughout the game can be culturally contextualized dependent upon the experiences of the player and how they interpret such things as: family, depression, school, innocence, purity, imagination, creativity, loneliness, friendship, and so. Perhaps they were disappointed that destroying and killing other creatures, beings, agents was not an option, but nearly all of them were able to engage with the idea of empathy – even if they’re unaware of it at the moment.

While some of my shy, but thought-provoking, students stood on their soapbox and exclaimed that A Bird Story failed to meet their expectations of a game with the lack of interaction (that they loosely defined) between the game and their physical bodies, omission of dialogue, mediocre design (I obviously disagree here as I adore the graphics) and unclear boundaries between reality, dream, and imagination, others found meanings I kicked myself for not seeing. For example, one element of design I’ve mentioned earlier is the game creators’ decision to make all the other characters, aside from the nameless child and wounded bird, mere shadows. With my mind sandwiched between Critical Race Theory and theories of Language Acquisition, I interpreted this decision as a way to bring inclusion across cultures and races and languages; while that’s not to say this wasn’t one of the intended purposes, many of my students interpreted these shadowy figures as a representation of the boy’s loneliness, his isolation – I find their perspective more beautiful than my own. Students also disagreed on the effectiveness of the soundtrack – some found it mismatched, and creepy, others found it relaxing and inviting; a few students found the game childish and meant to be a picture book for a younger audience while others maintained that children would be unable to understand the intricate details woven in through picture thought-bubbles and exclamation points, which could either mean anger, excitement, or surprise depending on the context of the scene(s). Despite all these differences, one thing we all came to agree upon after a lengthy discussion on rhetorical analysis is that the themes woven throughout the game can be culturally contextualized dependent upon the experiences of the player and how they interpret such things as: family, depression, school, innocence, purity, imagination, creativity, loneliness, friendship, and so. Perhaps they were disappointed that destroying and killing other creatures, beings, agents was not an option, but nearly all of them were able to engage with the idea of empathy – even if they’re unaware of it at the moment.

This brings me to my newly found love of Miguel Sicart. In his book Beyond Choices: The Design of Ethical Gameplay, Sicart makes an argument for emotional connections, moral complications, and ethical decisions that are mirrors of who we are as players and human-beings operating in and through various systems – internal and external:

“Understanding the design of ethical gameplay requires examining the ways the procedural and semiotic elements interrelate and translate systems…designing ethical gameplay consists of understanding how games operate and how players interact, engage, and learn these systems.”

Since my use of A Bird Story was intended to draw connections between narrative writing, narrative playing, and the rhetorical decisions we makes as authors (and players), and all the other various roles and ecosystems we find ourselves in, I’m not surprised that most of my students resist the notion of A Bird Story being a game, of this being considered “play” because it’s different. However, this resistance is seen throughout their interactions with our readings, course materials, day-to-day class schedule, living in another country, learning in a second language – thinking about our likes and dislikes, our internal value systems allows us to engage more critically with the decisions we’re faced to make from the outfit we’re going to wear to the person we’re going to marry. A game such as A Bird Story asks us not to make decisions about how the character will progress in his story, but to make decisions about empathy – it leaves an emotional footprint and challenges players to care and, in-turn, begin questioning the system of the game rather than interacting with the system blindly. It is this questioning that I’m guiding my students towards, not only through games but through close readings of authors such as Gloria Anzaldúa, Amy Tan, James Balwdin, and a few others who discuss the problematic and demoralizing constructs of racism and linguistic terrorism – which my students have revealed to be their current plights. If they can begin questioning the systems of the majority rather than blindly following rules they’re unsure if they actually value, then I feel I’ve done something worthwhile, I’ve followed through on a choice to break away from moldy, passed-down traditions that don’t align with my ethical stance on Second Language Writing instruction and given my students the option of choice.

Since my use of A Bird Story was intended to draw connections between narrative writing, narrative playing, and the rhetorical decisions we makes as authors (and players), and all the other various roles and ecosystems we find ourselves in, I’m not surprised that most of my students resist the notion of A Bird Story being a game, of this being considered “play” because it’s different. However, this resistance is seen throughout their interactions with our readings, course materials, day-to-day class schedule, living in another country, learning in a second language – thinking about our likes and dislikes, our internal value systems allows us to engage more critically with the decisions we’re faced to make from the outfit we’re going to wear to the person we’re going to marry. A game such as A Bird Story asks us not to make decisions about how the character will progress in his story, but to make decisions about empathy – it leaves an emotional footprint and challenges players to care and, in-turn, begin questioning the system of the game rather than interacting with the system blindly. It is this questioning that I’m guiding my students towards, not only through games but through close readings of authors such as Gloria Anzaldúa, Amy Tan, James Balwdin, and a few others who discuss the problematic and demoralizing constructs of racism and linguistic terrorism – which my students have revealed to be their current plights. If they can begin questioning the systems of the majority rather than blindly following rules they’re unsure if they actually value, then I feel I’ve done something worthwhile, I’ve followed through on a choice to break away from moldy, passed-down traditions that don’t align with my ethical stance on Second Language Writing instruction and given my students the option of choice.