This week I read a piece by Ed Smith called “Shut Up, Gaming Positivity,” in which Smith discusses what he sees as today’s “atmosphere of ‘gaming positivity.’ It’s a dream shared among developers and critics for gaming to be wonderful, smart, happy and successful—a willingness to force smiles and wave flags, even though it’s not helping.”

Indeed, Smith is concerned about such an atmosphere of gaming positivity because he critiques what he perceives to be the ultimate reasoning behind such praise:

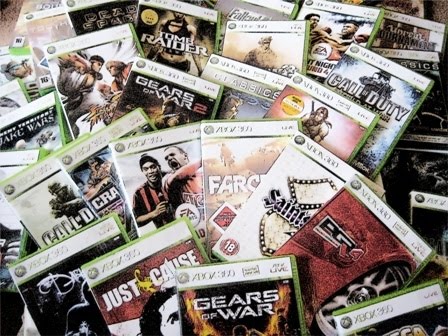

Rather than challenged by the emergence of different games and different creative voices, I feel like the culture of blithe acceptance in the gaming industry has simply widened. Old reviews of shooters and sequels, scaffolded by a checklist of “graphics, gameplay, replay value,” are today lampooned even by the big sites—I think anyone with the sense to not leave comments on things they read on the internet understands that gaming criticism, for a long time, was simplistic and toothless. But still I find myself wincing at the superlatives and hyperbole that I and others have used to describe games, even in articles I’ve written in recent months. Still I see a paradigm—a mental model—of championing games beyond all reason, in the hope their false glory will reflect back to us, the critics, a sense of validation.

In other words, this climate of gaming positivity, Smith argues, serves as a means of validating what we do—as a means of legitimizing games as a valid, rich area of engagement.

But even though Smith is critical of all this, he also is quick to note that gaming positivity “isn’t bad. In a culture besieged by sexism, consumers and retrograde politics of all kinds, it’s healthy to remind ourselves—even if it takes a little blurring of our vision—that games are worth something, that we do our jobs, as writers or game-makers, for a reward additional to our salaries. It’s nice to be nice.” But even though “it’s nice to be nice,” Smith continues, we need to be careful about the ways we talk about (and especially praise) games:

But even though Smith is critical of all this, he also is quick to note that gaming positivity “isn’t bad. In a culture besieged by sexism, consumers and retrograde politics of all kinds, it’s healthy to remind ourselves—even if it takes a little blurring of our vision—that games are worth something, that we do our jobs, as writers or game-makers, for a reward additional to our salaries. It’s nice to be nice.” But even though “it’s nice to be nice,” Smith continues, we need to be careful about the ways we talk about (and especially praise) games:

My problem with gaming positivity—this constant insinuation either tacit or direct that games are “better” than they once were—is that it assumes an end state, some kind of final evolutionary stage whereby artists and critics can rest easy. The spirit of blithe acceptance lives on in gaming positivity, only now disguised behind more sophisticated language. A smug, self-satisfaction has descended onto games. We have an independent scene, some slightly smarter mainstream releases and a game where you can play as a petal, and with that we seem satisfied. The tragedy, however, is that a lot of the truly great writing and games currently being published are being overlooked in favor of work that better suits a chirpy, videogame-positive zeitgeist.

I think Smith raises some interesting points here, and it has me thinking a lot about what we do and why we do what we do both in the gaming community and in academia. I understand the desire to legitimize one’s work or one’s field of study, but to do so through claims to high art or through, as Smith puts it, a “culture of blithe acceptance” is to enact an erasure of all the important things we could be exploring and critiquing in the field of video games. And such a mode of legitimization or validation seems to operate off exclusionary methods—the seeming need to show the value of games by placing them in some sort of sphere of high art or high culture, thereby perpetuating this binaristic system of value structured through so-called high and low art forms. And the problem with that is the manner in which such a system falsely delegitimizes those forms that are often viewed as the low ones, the products of mass or popular culture. So while I understand the desire to write about games in a way that seeks to shift our perspective of them, in a way that seeks to shift games’ situatedness from low culture to high culture, such a method simply reifies the hierarchical ways we often come to value certain media or art forms. And I don’t think that’s what games do. And I don’t think that’s what our writing should do either.

Rather, what I think matters about games (and the way we write about them) is the fact that our engagement with them affords us the opportunity to think about how the divide between high and low culture can (and should) be blurred, how the divide between different media forms can become muddled, and how a game (or a book, or a film, or whatever) can be more than one thing to more than one person. So I think it comes down to the idea of balance. We shouldn’t just blithely accept games, sure, but we also shouldn’t just blithely critique them either. Because it’s possible to both celebrate games and be critical of them at the same time—the two are not mutually exclusive. To engage in both mindsets at the same time, to both critique and celebrate at the same time, I think, would be a way to avoid the trap of writing about games in a way that, as Smith puts it, “leads to a cultural vacuum, an unwillingness to create and a moratorium on change.” Because games, of course, do keep changing, and should keep changing, just as all media and narrative forms do. And the ways that we write about all these things should continue to evolve and transform as well.

Rather, what I think matters about games (and the way we write about them) is the fact that our engagement with them affords us the opportunity to think about how the divide between high and low culture can (and should) be blurred, how the divide between different media forms can become muddled, and how a game (or a book, or a film, or whatever) can be more than one thing to more than one person. So I think it comes down to the idea of balance. We shouldn’t just blithely accept games, sure, but we also shouldn’t just blithely critique them either. Because it’s possible to both celebrate games and be critical of them at the same time—the two are not mutually exclusive. To engage in both mindsets at the same time, to both critique and celebrate at the same time, I think, would be a way to avoid the trap of writing about games in a way that, as Smith puts it, “leads to a cultural vacuum, an unwillingness to create and a moratorium on change.” Because games, of course, do keep changing, and should keep changing, just as all media and narrative forms do. And the ways that we write about all these things should continue to evolve and transform as well.