As we started our sixth year here at Not Your Mama’s Gamer, we pledged anew to do the work of social change, to work harder to take that work offline, and to pursue our Gaming for Good Initiative more aggressively. And with our pledge it seems that the universe heard us and offered us all of the opportunities that we needed. Not only did we just complete for our first streaming marathon to raise money for the National Breast Cancer Foundation this weekend, but we have found ourselves embroiled in a bit of a local battle that called for on-site activism.

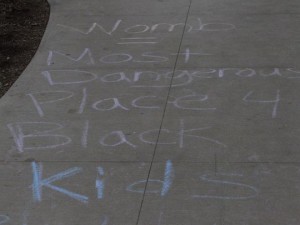

Recently we found ourselves teaching and learning on a campus where African American women were being bombarded with racist and sexist imagery under the guise of pro-life outreach. As African American women ourselves, this hit especially close to home. Our wombs were called dangerous spaces, African American women were labeled as being complicit in the attempted genocide of their own race. Also offensive about the entire campaign was the misappropriation of the rhetoric and imagery of the Black Lives Matter campaign. The fliers posted around campus bore the image of a fetus in utero with arms stretched to heaven with the tagline “Hands Up Don’t Abort.” Chalking on the ground in front of classroom buildings and (most noticeably) the Black Cultural Center disclosed such nifty facts as “Womb = The most dangerous place 4 Black Kids.” This campaign framed African American women as murderers of the same order as those who gunned down Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Laquan McDonald, Darrien Hunt, and John Crawford III; within that framing they managed to simultaneously negate the importance of the movement that sought to end the senseless and unjust murders of African Americans at the hands of corrupt police officers.

Recently we found ourselves teaching and learning on a campus where African American women were being bombarded with racist and sexist imagery under the guise of pro-life outreach. As African American women ourselves, this hit especially close to home. Our wombs were called dangerous spaces, African American women were labeled as being complicit in the attempted genocide of their own race. Also offensive about the entire campaign was the misappropriation of the rhetoric and imagery of the Black Lives Matter campaign. The fliers posted around campus bore the image of a fetus in utero with arms stretched to heaven with the tagline “Hands Up Don’t Abort.” Chalking on the ground in front of classroom buildings and (most noticeably) the Black Cultural Center disclosed such nifty facts as “Womb = The most dangerous place 4 Black Kids.” This campaign framed African American women as murderers of the same order as those who gunned down Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Laquan McDonald, Darrien Hunt, and John Crawford III; within that framing they managed to simultaneously negate the importance of the movement that sought to end the senseless and unjust murders of African Americans at the hands of corrupt police officers.

Unfortunately this is not the first time that we have seen the co-opting of #BlackLivesMatter. Calls for justice using the hashtag were met with severe backlash and the creation of hashtags like #alllivesmatter and #copslivesmatter. The former sought to minimize the importance of the original hashtag by making the argument that Black lives were no more important than the lives of other races and that our cultural and historical situations were no different from anyone else’s and as such they did not deserve special consideration or dispensation. Meanwhile, the latter sought to justify the actions of the police officers who had committed the murders by making the excuse that they had done so simply to protect their own lives. This misappropriation (or colonizing) of hashtags, of lives, of narratives at the hands of those whom it does not belong to and for purposes that are contrary to their creator’s continues to happen in myriad ways.

Jamie Broadnax, creator of Black Girl Nerds, recently published a piece on the colonization of Black Twitter that exposes the colonization of Black lives and narratives. Evidenced by a series of Black erasures in the media industry from the fact that James Franco is going to direct and star in a film based on the Twitter story written by Aziah “Zola” Wells to the revelation that white, British actor Joesph Fiennes would play Michael Jackson in a satirical comedy. Ironically, Fiennes justified his casting by saying that he was closer in skin color to Jackson than a Black actor would be. Closer in skin color. Because that is what matters, the color of skin. Not the depth and singularity of experience. Experiences that belong to African American people and can not be understood in any manner of fullness by a white, British celebrity. Lives stolen, cultures colonized out of a lack of understanding that being African American is so much more than just the amount of melanin in your skin.

Even when the opportunity to celebrate or reclaim the language and history of African Americans in an attempt to find some common ground for unification in a time that racism (and attempts at what often feels like genocide) are at their peak, those who would silence or co-opt that narrative often turn violently against it. When Beyonce released the video for her latest single, “Formation,” which is at it’s core, a pro-Black trap anthem, a wall of resistance was met as the imagery of the Black Power Movement flashed across screens and marched across the Superbowl field. In “Formation” Beyonce venerates things that embody her particular flavor of Blackness and Black life. Her litany includes paying homage to her own Black and Creole heritage, Black hair and flared nostrils, and the ever present bottle of hot sauce in her bag (FWIW I want to know if she’s gone with the Creole favored Tabasco or the Frank’s Red Hot.)

Even when the opportunity to celebrate or reclaim the language and history of African Americans in an attempt to find some common ground for unification in a time that racism (and attempts at what often feels like genocide) are at their peak, those who would silence or co-opt that narrative often turn violently against it. When Beyonce released the video for her latest single, “Formation,” which is at it’s core, a pro-Black trap anthem, a wall of resistance was met as the imagery of the Black Power Movement flashed across screens and marched across the Superbowl field. In “Formation” Beyonce venerates things that embody her particular flavor of Blackness and Black life. Her litany includes paying homage to her own Black and Creole heritage, Black hair and flared nostrils, and the ever present bottle of hot sauce in her bag (FWIW I want to know if she’s gone with the Creole favored Tabasco or the Frank’s Red Hot.)

“Formation’s” message of self-love, Black pride, and unity was quickly dismissed as sexualized, vapid, and meaningless by an onslaught of social media critics who were (and are) incapable of understanding the depth and meaning of the narrative that Beyonce brings front and center. The dissemination of this narrative in such a public arena caused “offense” so great that our newsfeeds and timelines are filled with White folks’ terror of the re-emergence of the Black Panthers and the equating of them with the Ku Klux Klan, as though the Black Panther Party was guilty of the same terrorism, rape, and murder as the Klan and that we see mimicked by the police today. In the racist cries of “disrespectful to ‘our boys in blue’” we see an erasure of the crimes that have left Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin(Trayvon Martin), Samaria Rice (Tamir Rice), Lesley McSpadden (Michael Brown), Geneva Reed-Veal (Sandra Bland), Erica Garner (Eric Garner), and Michelle and Bolus McMillen (Gynna McMillen) without their sons, daughters, and fathers and rendered 13 women and girls (that we know of) the victims of sexual assault at the hands of the police officer who targeted them because they were poor, Black, and powerless.

meaningless by an onslaught of social media critics who were (and are) incapable of understanding the depth and meaning of the narrative that Beyonce brings front and center. The dissemination of this narrative in such a public arena caused “offense” so great that our newsfeeds and timelines are filled with White folks’ terror of the re-emergence of the Black Panthers and the equating of them with the Ku Klux Klan, as though the Black Panther Party was guilty of the same terrorism, rape, and murder as the Klan and that we see mimicked by the police today. In the racist cries of “disrespectful to ‘our boys in blue’” we see an erasure of the crimes that have left Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin(Trayvon Martin), Samaria Rice (Tamir Rice), Lesley McSpadden (Michael Brown), Geneva Reed-Veal (Sandra Bland), Erica Garner (Eric Garner), and Michelle and Bolus McMillen (Gynna McMillen) without their sons, daughters, and fathers and rendered 13 women and girls (that we know of) the victims of sexual assault at the hands of the police officer who targeted them because they were poor, Black, and powerless.

The minute the Black community calls forth a formation, we’re immediately told we’re too defensive, too preoccupied with something that’s not real; and, yet, our world continues to be a hostile space stained with racism and hate speech directed towards Others. Our calls to join forces are being met with the static of #alllivesmatter. What we have noticed, though, is the power of presence, the power of voice, the power of formation as we continue to move forward in our concerted efforts of sustained, mobilized activism. Our decision to march together on a predominately white campus to a predominately white, pro-life group’s meeting and peacefully sit-in, served, if nothing else, to let them know that we will no longer tolerate the misappropriation and colonization of our bodies and narratives for their personal gains. Like the public response to “Formation,” our on-campus call for Black self-love has been accused of being both dangerous and volatile by a group that continues to be unwilling (and unable) to understand the depths of the narrative put forth by #Blacklivesmatter and “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot.”

One thought on “Formation: The Move Against the Colonization of Black Bodies and Narratives”

Very well said!