I’ve been writing a lot the past couple weeks about metanarrativity and postmodernism, about how such things manifest themselves in games like The Magic Circle, like Until Dawn, like Pony Island. And I hope you’ll bear with me while I indulge myself in expanding on some of these ideas a little more.

Indeed, a couple weeks ago, a wrote about how Pony Island makes use of metafictional techniques in order to allow us to interrogate the boundaries of the game world, to interrogate our roles as players, to interrogate the roles of developers. And last week, I worked to address the use of metanarrativity in games more broadly by exploring the manner in which other games—games like Until Dawn and The Magic Circle—make use of metafictional frameworks in a way that seems representative of Linda Hutcheon’s discussion of postmodern metafiction as an enactment of a sort of paradoxically complicitous critique. But, in light of such examinations, I’ve been thinking a lot about how it is, exactly, such games go about doing all this. In other words, how is it that games make use of metanarrativity? How do they ask us to engage with their metanarratives? And how do they ask us to engage with such metanarratives differently than other media or textual forms?

Indeed, a couple weeks ago, a wrote about how Pony Island makes use of metafictional techniques in order to allow us to interrogate the boundaries of the game world, to interrogate our roles as players, to interrogate the roles of developers. And last week, I worked to address the use of metanarrativity in games more broadly by exploring the manner in which other games—games like Until Dawn and The Magic Circle—make use of metafictional frameworks in a way that seems representative of Linda Hutcheon’s discussion of postmodern metafiction as an enactment of a sort of paradoxically complicitous critique. But, in light of such examinations, I’ve been thinking a lot about how it is, exactly, such games go about doing all this. In other words, how is it that games make use of metanarrativity? How do they ask us to engage with their metanarratives? And how do they ask us to engage with such metanarratives differently than other media or textual forms?

I think, for me, this question of “how” really comes down to a game’s mechanics—to the way our gameplay is oriented and framed. And I think it’s important to think about these mechanics when thinking about the narrative components of a game because we can’t separate a game’s mechanics from its narrative—and we can’t separate these things because the way we play a game drives its story forward, and the way a game tells its story orients the way we play it. And this linkage seems especially apparent when dealing with metanarrative because the metanarrative is meant to highlight the process of play, thereby making us even more aware of how we play the game and why we play the game that way.

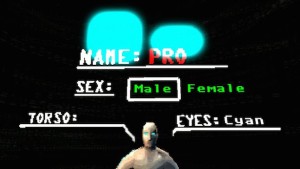

As a result, the manner in which a game’s metanarrative and mechanics intersect, the manner in which they work in tandem, seems especially revealing of the ways both work together to reveal the game’s goals. In games like The Magic Circle and Pony Island, for instance, games that make use of metafictional moments in an effort to make us interrogate the processes of making and playing games, we are asked to, essentially, hack the games, to break them, to take control of them from the inside, to, as the Old Pro, a character in The Magic Circle puts it, “finish” the game. And in order to hack these games, in order to finish them, it seems that such games ask us to first hack ourselves—to question our roles as players—for, as the Old Pro also says, “we gotta start by breaking you.”

As a result, the manner in which a game’s metanarrative and mechanics intersect, the manner in which they work in tandem, seems especially revealing of the ways both work together to reveal the game’s goals. In games like The Magic Circle and Pony Island, for instance, games that make use of metafictional moments in an effort to make us interrogate the processes of making and playing games, we are asked to, essentially, hack the games, to break them, to take control of them from the inside, to, as the Old Pro, a character in The Magic Circle puts it, “finish” the game. And in order to hack these games, in order to finish them, it seems that such games ask us to first hack ourselves—to question our roles as players—for, as the Old Pro also says, “we gotta start by breaking you.”

Games like Until Dawn and Life is Strange also make use of such metafictional interrogations, but instead of asking us to question our roles in the game through the use of hacking-oriented gameplay, they seek to heighten our awareness of the choices we make as we play through the fact that our gameplay is, ultimately, choice-based in these games. Indeed, the psychiatrist in Until Dawn, for example, says, “I am trying to help you. And this game you’re playing…you understand that it’s not good for you…it’s not good for anyone. And I can’t say that you’re being particularly honest in the way you’re playing.” And such statements, statements that draw our attention to the fact that we are playing a game, also draw our attention to the way we play the game, to the choices we make as we play.

Games like Until Dawn and Life is Strange also make use of such metafictional interrogations, but instead of asking us to question our roles in the game through the use of hacking-oriented gameplay, they seek to heighten our awareness of the choices we make as we play through the fact that our gameplay is, ultimately, choice-based in these games. Indeed, the psychiatrist in Until Dawn, for example, says, “I am trying to help you. And this game you’re playing…you understand that it’s not good for you…it’s not good for anyone. And I can’t say that you’re being particularly honest in the way you’re playing.” And such statements, statements that draw our attention to the fact that we are playing a game, also draw our attention to the way we play the game, to the choices we make as we play.

And I think that these types of intersections of (meta)narrative and mechanics, of storytelling and gameplay, are what allow games to make use of metafictional elements differently than other media forms. But perhaps such differences also allow us to think about the similarities as well—perhaps they allow us to extend this line of thinking by considering how it is we engage with metanarrative more broadly and how it is we interact with other forms as well.

I was thinking about all this the other day while I presented a paper at a conference on a panel entitled “The ‘Contemporary’ Across Media.” And during the Q&A portion, one member of the audience asked us how we might define “the contemporary” in light of our discussion that day. It’s a big question, to be sure, and one that I’ll continue to grapple with for a while, but I think that thinking through some of the above ideas—things like the intersection of metanarrative and mechanics and the manner in which such an intersection allows us to think about how we interact with a variety of media forms—is one way for me to get at an understanding of our contemporary moment. Because, as my panel title seems to reveal, it’s definitely a moment that’s occurring “across media.”