In academia, there are constant fights about disciplinary boundaries: you can’t teach ethics in a course: that belongs to philosophy; you can’t say the word history in a course description; you can’t touch certain authors. Disciplinary boundaries can be a good thing: they let scholars know they have a home; they bring a certain legitimization to a field; they help otherwise confused students really define what they want to do with their lives and what they want to study. They can also be a bad thing: they block innovative ideas that could come from a diverse group of people with different expertise; they limit the reach of otherwise important scholarship because it may only be seen as discipline specific; it also causes disciplinary fighting, when we really need to be allied against things such as corporate takeovers of education and looking out for our students. But why am I talking about this on NYMG?

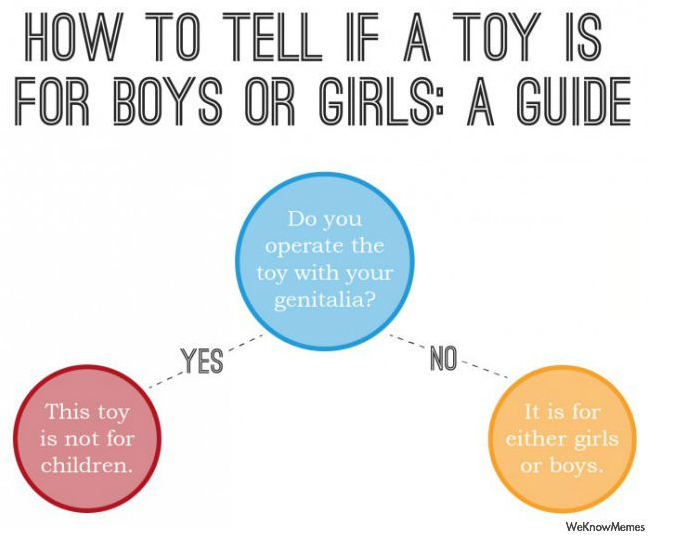

Game Studies as a field is growing. What is Game Studies proper? It’s not necessarily the making of games or game design, but the study of games. I define it as the study of games as socio-cultural, rhetorical artifacts. Yes, a mouthful, but accurate I think. And just like race can be a part of every discipline and every class to some degree relies on writing, gaming is beginning to be used in a variety of disciplines because of their growing popularity and cultural impact. My question here today is: is this a good thing?

Is it a good thing for a history professor to teach a history of games course? Is it a good thing for a College of Management prof to teach the business of selling video games alongside movies and music? Those of us who have studied games for years, who have read game scholarship from Huizinga to Salen and Zimmerman to Juul to Aarseth and on and on and on, are rightfully skeptical. Playing games doesn’t equal disciplinary level knowledge of how games impact players, the economy, the culture, and so on. Just like writing doesn’t equal best practice knowledge and strategies for writing. Because I can mix a vodka-club soda doesn’t make me qualified to teach a chemistry class.

On the other hand, I watch my students–who have never studied video games in any official capacity–absolutely internalize many major tenets of game studies. Before reading one line of Huizinga, they have internalized the idea of the magic circle. Before reading Nakamura, they can intuit problems representing race digitally. They think of things, with a level of depth and understanding, that I know I haven’t taught them. I simply opened the door for them to formally explore things they experience and gave them words to express things that were already unsettling to them. Sure they have learned a ton in the class so far, but they do understand games on a deep level from being immersed in them.

If it’s true that players can come to a deep level of understanding of games, then why wouldn’t other instructors be able to as well? With some reading into the extant body of knowledge of Game Studies, it seems possible. That said, what are the motivations for wanting to teach through games? Is it because games are finally gaining scholarly legitimacy and thus are acceptable in diverse classrooms? Or is it recognizing the future of gaming and wanting to stick the term into as many fields as possible to ride the coattails of their popularity? It’s probably some combination of genuine interest and wanted to get students into courses they otherwise wouldn’t enroll in.

Honestly I don’t know if that’s a bad thing. I would love to see a course on biology and video games or construction and gaming. I worry, of course, that the curriculum wouldn’t represent the amazing body of knowledge Game Studies has fought to build, but isn’t that always a risk? And is that risk worth it even if it does happen with some regularity? I guess the main question is this: do we want games to be taught widely, regardless of the cost? I think I do, so I hope that those who pick up the mantle of games and infect (in the best possible way) their discipline will do so with caution and care. What do other game scholars think? The more the merrier? Or do we need to maintain our disciplinary rigor to grow without collapsing?

One thought on “Doing Games: The Expansion (and Collapse?) of Game Studies”

Hmm . . . while I’m sensitive to the issues you’re raising, I’m also very skeptical that we’re anywhere near figuring out what “game studies” is. Sure, it’s not necessarily making games or marketing games, but it’s not necessarily not those things, either. I have always assumed that game studies is inherently interdisciplinary. Both Huizinga and Nakamura utilize knowledge from other disciplines to support their arguments and analyses–sometimes doing so in a way that might raise eyebrows among the disciplinary experts. Some of the most stunning insights I’ve had as a scholar and teacher have come from students who have used their own disciplinary expertise to question or push a point. Frankly, I’m not sure a model of scholarship built on medieval concepts of artisanal specialization and apprenticeship best serves the medium or our efforts to understand it.

Implicitly, you’re also asking questions about organizational structure–where game studies fits in a given university structure. I’ve been building a games study curriculum at my own school, and that curriculum is being built without a specific department or program in game studies. And I’m not sure I want one. Instead, we’re looking to build a cross-departmental program and, with it, a diffuse group of experts who bring their interests and expertise to the conversation (i.e., theater, communications media, educational technology, art, art history, etc.). Yes, we’re looking to raise enrollment, but also to figure out how to get the smartest people into the conversation. More informally, I’m looking to enable faculty who recognize the need to incorporate game texts into their courses–enable them to teach them well in terms of the existing discourse of game studies as you define it, but also to articulate that discourse with their own.

No, knowing how to mix a good vodka and soda doesn’t make me a chemistry expert, but if I dedicate my time to learn a bit of chemistry and, even better, take the time to talk to a chemist about it? And If I can give my students the chance to hear that conversation–and to add their own expertise? Sounds pretty good to me.

By the way, your point about student expertise is spot on. I’ve never, in over 20 years of teaching at the university level, had students with the level of literacy, engagement, and sophistication as I’ve had in my game courses.