In my continued efforts to see the end of war, I’ve kept with playing This War of Mine: The Little Ones. In my last post I mentioned that the major draw of this game (for me at least) is the often neglected story that other games like Call of Duty, Ghost Recon, and Gears of War don’t tell, I’ve become aware of this war within a war that takes place between civilians. While the game certainly focuses on the refugee

perspective of survival, it not only tells a story of loyalty, camaraderie, and morality between survivors but it also delves into personal stories that shape  responses and outcomes to your decisions as a player. It’s in these stories that I’ve found myself entangled, imagining (knowing) my actions are directly responsible for the tragedies and successes the characters experience. What’s more, the conflict that arises between the characters I play and the other survivors causes great moral dilemma in every fiber of my being; in order to to get my characters through the worst experiences of their lives, I have to steal from and kill others who are enduring the same war.

responses and outcomes to your decisions as a player. It’s in these stories that I’ve found myself entangled, imagining (knowing) my actions are directly responsible for the tragedies and successes the characters experience. What’s more, the conflict that arises between the characters I play and the other survivors causes great moral dilemma in every fiber of my being; in order to to get my characters through the worst experiences of their lives, I have to steal from and kill others who are enduring the same war.

As the daughter of a Marine and an avid reader of WW2 novels, I’m no stranger to stories of combat and bootcamp, shooting ranges and guns, PT and fatigues. The stories I have heard, however, tell the side of military – there is a clear enemy and a clear hero and “we” are always in the right. The stories I read, on the other hand, are more nuanced in unraveling the overlooked experiences of unsuspecting civilians. The history classes I took didn’t teach me about the children riding tricycles in their front yards when we dropped the atomic bomb; I learned that by actually visiting the museum in Hiroshima, Japan. Reflecting on all of these experiences on my own sheds light on what compels me to continue through this game despite the anxiety, frustration, and occasionally the tears. And this all comes about through the mechanics of the game which force you to consider the positionality of yourself as the player, your characters, and the civilians and snipers you interact with throughout your play session.

In the last week, I’ve put roughly 10 hours into this game, attempting to learn the mechanics, think more strategically, and hardening my heart just enough to be okay with stealing from elderly people, ignoring a needy a child tugging at me for a hug while attempting to build a bed, hitting people with shovels so that I can run off with their food and medicine, and deciding which of my characters should eat and which can go another 24 or 48 hours starving and who deserves to sleep and who needs to continue guarding. When neighbors knock on my door I need to decide if I’ll help protect their daughter from rebel military threatening to rape her, give medicine to kids wanting to help the ill mother, or turn in a neighbor to the rebels in exchange for food, coffee, cigarettes, and medicine. If I notice a character is depressed or broken, should I have another one talk to him or her or ignore their emotional turmoil?

In the last week, I’ve put roughly 10 hours into this game, attempting to learn the mechanics, think more strategically, and hardening my heart just enough to be okay with stealing from elderly people, ignoring a needy a child tugging at me for a hug while attempting to build a bed, hitting people with shovels so that I can run off with their food and medicine, and deciding which of my characters should eat and which can go another 24 or 48 hours starving and who deserves to sleep and who needs to continue guarding. When neighbors knock on my door I need to decide if I’ll help protect their daughter from rebel military threatening to rape her, give medicine to kids wanting to help the ill mother, or turn in a neighbor to the rebels in exchange for food, coffee, cigarettes, and medicine. If I notice a character is depressed or broken, should I have another one talk to him or her or ignore their emotional turmoil?

The characters’ gender also seems come into play: women tend to be better at bargaining and men tend to be stronger and more agile. One will question the decision they made (because they’re a unit) while another will recognize that there are no true survivors of war — no one gets out whole, everyone is just trying to make it another day. Because there is never any consensus between characters on what is right or wrong, you, the player, quickly realize that ethics and morals won’t always keep you alive or even keep you true. And this is probably the only game that uses guilt as a mechanic in that every decision acts like a character of its own, causing ripple effects that reach even the epilogue. Sure, you can be a martyr and sacrifice your own needs for others, but is that really the point of such a game? Is that really what you would do if such a situation was your reality?

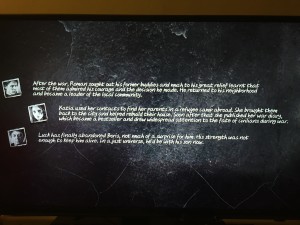

While I did finally see the end of war (in a co-play session with my partner), it wasn’t without its struggles. I learned, in previous failed playthroughs, that one of my characters was caught by human traffickers on her escape route to Canada, one character committed suicide, two characters chose to leave even after I nearly killed another character attempting to get bandages and food for them, and children had nightmares, wet the bed, and became physically broken. But, I kept playing. I thought, I hoped, that the end of war would be this miraculous experience; all the death, hurt, trauma, and ethically questionable decisions would be “worth it”. What I found was: there is no end to war. It’s not like graduating a program and starting a new life with nothing but hope on the horizon. The post-script to winning left me unsatisfied, reminded me of all the fucked up things I did to survive. There’s no leaving this game clean, there’s no clear cut escape;  you’re almost trapped inside the cycle of PTSD with your characters, having dreams of your own, becoming attached to each character you play and wishing there was something more you could have done. I often find myself thinking of the young woman trafficked: which of my decisions led her there?

you’re almost trapped inside the cycle of PTSD with your characters, having dreams of your own, becoming attached to each character you play and wishing there was something more you could have done. I often find myself thinking of the young woman trafficked: which of my decisions led her there?