Alison Rapp’s recent harassment and ultimate firing from Nintendo of America is yet another example of a phenomenon I have been becoming more and more concerned about: internet shaming. Her story is terrible and terrifying, but unfortunately, it’s not uncommon. The implications of Internet shaming by Internet mobs are bigger than just the gaming community or the tech community, these stories have implications for us all. The Internet provides anonymity and distance, and a forum for getting our voices out. Through social media platforms, like Twitter, we can gain support for our cause, or sometimes, we can use it to gang up on people. It seems new Internet mobs pop up almost daily, with people feeding off each other’s anger to pile on someone who has been perceived to have done some horrible thing.

This trend is so terrifying, especially because the people who the Internet mobs go after are often just regular people who made a mistake or made a bad judgment in wording their tweet or they posted the “wrong” picture. I recently read Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, in which he interviews and some of the victims of these Internet campaigns. If you haven’t read the book, his Ted Talk on the subject gives an overview of two of the stories in his book, those of Jonah Leher and Justine Sacco. He begins his talk by describing some of the early benefits of Twitter:

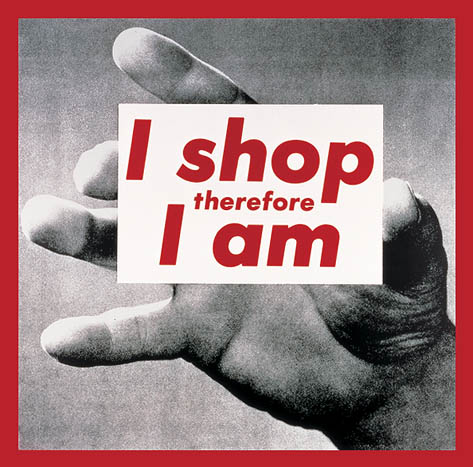

In the early days of Twitter, it was like a place of radical de-shaming. People would admit shameful secrets about themselves, and other people would say, “Oh my God, I’m exactly the same.” Voiceless people realized that they had a voice, and it was powerful and eloquent. If a newspaper ran some racist or homophobic column, we realized we could do something about it. We could get them. We could hit them with a weapon that we understood but they didn’t — a social media shaming. Advertisers would withdraw their advertising. When powerful people misused their privilege, we were going to get them. This was like the democratization of justice. Hierarchies were being leveled out. We were going to do things better.

Sounds great, except we aren’t just getting powerful people who have done horrible things. Instead, the Internet mobs often go after pretty powerless people, and they dig and dig and dig until they find something they can spin as awful. Granted, sometimes these shaming campaigns are aimed at people who are more powerful or more privileged. And, Ronson addresses that with his narrative of Jonah Leher, a best selling author who was accused of plagiarism. But, even then, the power of the Internet mob gets ugly, as Ronson wrote of the Twitter shaming aimed at Leher:

Power shifts fast. We were getting Jonah because he was perceived to have misused his privilege, but Jonah was on the floor then, and we were still kicking, and congratulating ourselves for punching up. And it began to feel weird and empty when there wasn’t a powerful person who had misused their privilege that we could get. A day without a shaming began to feel like a day picking fingernails and treading water.

The Internet gets ugly fast. I hadn’t heard of Alison Rapp before she was fired, but that night I pulled up Twitter and watched the Internet just pile on. I was encouraged to see a lot of support and kindness, but the ones who wanted to get her, put a frightening amount of effort into doing just that. They dug and dug and dug (and had apparently been doing so for months). But, many of those who were so intent on getting her refused to even consider that there might be more to the situation, that there might be some nuances we should consider. It seems that recognizing nuance and showing compassion for others isn’t the point. But, I don’t know what the point is. What is the end game of public shaming?

I teach college students, and I often talk about social media. Each time a public shaming situation blows up, I bring it into the classroom because we need to talk about it. And because it could happen to anyone. I ask my students how they decide what to post and if the platform (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, etc.) changes how they think about audience and, if so, does it change what they feel comfortable posting. I often hear that they don’t worry about it much. Or, “I’m friends with my mom, so as long as it wouldn’t upset her, I don’t worry.” But, that attitude scares me because your mom probably loves you; the Internet does not. I don’t know the answers or how to fix it, but we need to keep talking about it.

One thought on “Public Shaming is Everyone’s Problem”

I’ve followed the GamerGate and similar shaming type campaigns for the past few years, and there’s one thing I just realized as I read you article. If you look at comments about Anita Sarkeesian, Brianna Wu and Zoe Quinn in the beginning and currently, you read the same comments. For Sarkeesian, its a lot of “she’s a liar.” Yet, what we’re seeing in response is the creation of a platform for these women to voice concerns, make criticism and work towards change. I believe that the three women mentioned above created a website that is meant to help those being targeted online. The problem though is that the laws and individual site’s policies do not seem to be catching up or paying attention, which is sad considering the potential harm. Its hard not to consider how kids are being cyberbullied and then try to commit suicide. Its impossible to make the parallels, which makes you think what similar thoughts and actions have the women being targeted had.