Despite how problematic I find Bogost, most of the time, he is right about some stuff. In Persuasive Games, Bogost writes, “video games deploy more abstract representations about the way the world does or should function” (100). I’ve written several blogs about how historicity functions in games like Civilization, focusing on the reappropriation, or rather, recasting of historical artifacts and events within a new, player-determined timeline. The Tropico series is certainly no stranger to this type of rehistoricalization. And I think by examining Tropico alongside its counterparts, we can see an interest, and at times disturbing, trend in how video games are abstractly arguing about how the world functions.

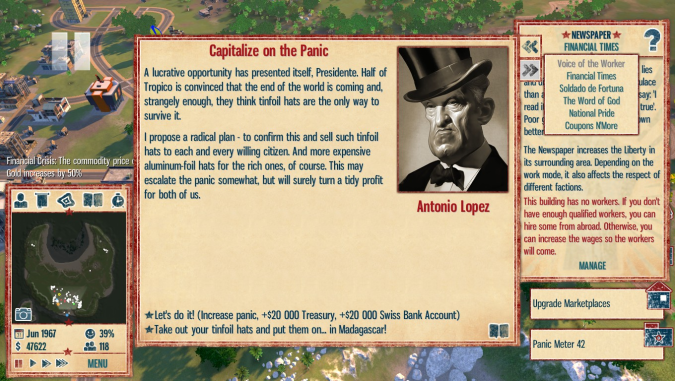

Like Civilization, Tropico has focused more and more on social policies as the series evolved. In the most recent DLC available, Modern Times, the world of Tropico is introduced to things such as organic farming, terrorism, and decreased productivity due to social networking sites like Facebook. Healthcare reform, Internet police, and edicts like the Police State ensure that your citizens stay healthy, productive, and in line. Most of the additions in the Modern Times expansion seem to have a decreased effect on liberty, while the only ways to keep your liberty happiness up remain through various telecommunication or media outlets like newpapers and TV stations.

One of the most interesting recent additions is the game’s new focus on terrorism. From a new “threat level” indicator that penalizes you for each step below “green” your meter gets, to random terrorist bombings, the new Tropico suggests that we see the world in increasingly precarious conditions. In the main game of Tropico 4, your threats are leaders drunk with power, overcoming poor land conditions, trying to keep rebellious workers in line, and other cold war era problems. But Modern Times betrays our fears of uncontrollable enemies that come out of no where.

However, in the main game you also face faceless enemies who want to destroy you. Often you are tasked with uncovering who this rebel is by paying off a faction leader or patiently providing goods to others in order to get clues to his or her identity. The difference is in the way you need to combat the enemy in the new expansion. In the previous game you fight the person by exposing who they are and then doing some political jockeying to either get them on your side or discredit them in the international community. In Modern Times, you spend your time saving leftover power from powerplants to charge up your weapons in case of an attack, pouring money into scientific programs to develop the next great weapon, or funding research projects that have no known outcome. In almost all main-line missions, you are provided with the consequences of your actions (ie. if you choose to execute this person you will lose respect from the intellectual community, if you let them go there will be 10 rebels added to your island). In Modern Times, you spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on things when you have no idea what the outcome will be.

This expansion exposes a view of the world as uncertain; where we have to spend as many resources as possible on an invisible and unknowable threat. Money is still what talks loudest, but you never know when the next building will blow up, when an epidemic will close down your entire island, or when the research you’ve been spending $2500 a month on for a year will pay off and get you that next great weapon.

One thought on “Threat Level Red: Modern Problems in the ‘Tropico 4’ Expansion ‘Modern Times’”

Someone on TVtropes had this to say about the game:

“The message behind the game is extremely cynical. It basically says that all political leaders are there to either line their own pockets or just to hold power. Whether capitalist or communist, ideology is merely a way to obtain more power. The Cold War setting heavily reinforces this notion by having Tropico essentially be a very small pawn in a much larger game betweem the US and the USSR that is the same money-making, power-grabbing scheme on a larger scale. In addition, all of the factions are completely cynical examples illustrating the worst of their particular group as a whole: the religious faction is full of puritanical Moral Guardians, the capitalists are greedy plutocrats, the communists want you to keep everyone equal regardless of skill or effort, the militarists are club-wielding Black Shirts, the nationalists are xenophobic shut-ins, the environmentalists are so knee-jerk hateful of industries such as logging that they would rather have people unemployed than working at a mill, the intellectuals are prone to get offended at anything done to appeal to the uneducated, and the loyalists are universally depicted as a bunch of boot-licking simpletons who measures a strong leader on how much he abuses his privileges, cultivates a near-religious cult of personality, and brutally oppresses the general population.”