Not long ago, I wrote about looking at some of the studies on how men see women (and vice versa, and how we see our own genders) from a game design angle. Studying what eye trackers reveal about how we look at bodies can tell us a lot about media, I think, and this came back into focus for me recently when I read a piece offering advice for designing female superheroes in a way that presents strength over hypersexualization. You may have seen it — award-winning artist Renae De Liz’s series tweets of advice on adjusting presentation of women heroes was reposted everywhere, and her advice not only raises some valid (and long-standing) concerns about the presentation of female superheroes, but also echoes some of our own critiques about heroines in games.

De Liz chose DC heroine Power Girl for her example, and offered advice to those who are interested in changing characters designs but aren’t sure how. This is a key point (and one that was ignored by many detractors), because it addresses a number of obstacles to changing the way created women are presented in media. There are precious few examples in comics history of heroines who didn’t fit certain tropes, and even now some of those are holdovers because they are expected, and we see a similar trend in video games. How do people begin to create change without models to draw from? It’s possible, but more difficult, and it’s easier to just repeat the kinds of design decisions that have been successful in the past, particularly when there’s a lot of money on the line. Using the example from my previous post of Jade from Beyond Good & Evil, though Jade was purportedly designed in response to hypersexualized female characters, Jade still bears a lot of the same marks, most notably design lines that direct the eyes toward her physical attributes. As you can see in De Liz’s Power Girl examples, she’s made steps to move away from those kinds of visual directives.

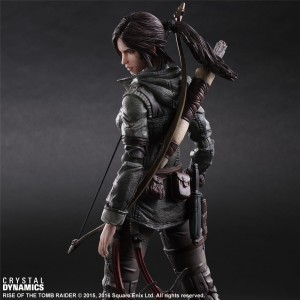

Gone is the boobs-and-butt pose meant to display all Power Girl’s assets at once, but gone too is the arrow in her cleavage that directs the eye to her breasts. Now, cleavage certainly can create that effect, when someone is particularly large-breasted or wearing a special bra, but we’re talking here about an artist’s choice, and as De Liz demonstrates, it’s completely feasible to draw a woman who still has large breasts (tucked securely into a sports bra) without creating that effect. She’s also drawn the heroine’s body a little wider, stronger, with visible muscle tone, something I’ve also addressed before, and something I think is very important for women heroes. We need to see that they are strong, that it’s okay to be strong. Occasional NYMG contributor Carol Hood wrote, after the death of wrestling star Joanie “Chyna” Laurer, life can be difficult for young girls navigating the world in strong bodies, because there are so few strong female bodies shown to them. Characters like Lara Croft are supposed to navigate extreme physical circumstances while remaining delicate and beautiful, with arms and legs more like the Power Girl on the left than the one on the right.

Gone is the boobs-and-butt pose meant to display all Power Girl’s assets at once, but gone too is the arrow in her cleavage that directs the eye to her breasts. Now, cleavage certainly can create that effect, when someone is particularly large-breasted or wearing a special bra, but we’re talking here about an artist’s choice, and as De Liz demonstrates, it’s completely feasible to draw a woman who still has large breasts (tucked securely into a sports bra) without creating that effect. She’s also drawn the heroine’s body a little wider, stronger, with visible muscle tone, something I’ve also addressed before, and something I think is very important for women heroes. We need to see that they are strong, that it’s okay to be strong. Occasional NYMG contributor Carol Hood wrote, after the death of wrestling star Joanie “Chyna” Laurer, life can be difficult for young girls navigating the world in strong bodies, because there are so few strong female bodies shown to them. Characters like Lara Croft are supposed to navigate extreme physical circumstances while remaining delicate and beautiful, with arms and legs more like the Power Girl on the left than the one on the right.

What I like most here, though, I think, are not these big, obvious changes, but the smaller changes of pose and purpose. De Liz made changes to pose that are obvious here, but also to the position of Power Girl’s hands, moving her stance, her very being, from vulnerable to purposeful. The character on the right is about to kick some ass. You can see it. You don’t need dialogue or sound; it’s there in her presence. Her face, too, is changed. No longer is Power Girl the sultry vamp about to slip a double entendre into her one-liner. She is strong, clear-eyed, determined. She’s a hero.

And this isn’t to say we can’t have the Power Girls on the left. There’s plenty of room for vamps. The problem comes when all our heroines are supposed to be both, but only look like the woman on the left. Save the world, all without breaking a nail or a sweat (unless it’s a sexy sweat)? No pressure, though, and thank goodness for super powers.

Skimpy outfits can be sexy, but so can capability, and we don’t see enough of that on display. What’s more, heroines fighting to save the day, the world, a dog, a child, their friends, or anyone, aren’t there to be sexy. Sexy is a sideline. They’re there to save the day. We don’t have to make that more difficult by requiring that they all do it in heels and camisoles or tube tops.