This year at the Games+Learning+Society conference, I’ll be presenting with my friend and colleague Cody for the Well Played series. Our presentation, titled “Just Give me the Controller: Scaffolded Learning, World Building, and the Witness,” will focus on how the game The Witness is able to create an environment that is not only built on the principles of scaffolded learning and zones of proximal development, but rather the learning is the game. In other words, the learning in the game isn’t the means to an end; you don’t “master” all the skills necessary and then actually play the game. The game is in the learning. In an age where gamification, pointification, and any of the other -ifications have exploded with popularity and are being implemented often without background or consideration, the way The Witness is able to teach is truly novel. In this post, I will give some of the background to what scaffolded learning and zones of proximal development are as well as give some teasers for how it ties into The Witness. As we usually do at NYMG, I’ll write a wrap up and more in depth post about the conference afterwards.

When Vygotsky posited his now famous theory of Zones of Proximal Development, often synonymous with scaffolded learning, Russian schools were only testing things students were already supposed to know. Shifting this, he said the more important question is what they can accomplish with assistance, since one rarely does everything alone:

“Over a decade even the profoundest thinkers never questioned the assumption; they never entertained the notion that what children can do with the assistance of others might be in some sense even more indicative of their mental development than what they can do alone.”

This was and still is a revolutionary idea in education. It almost seems that despite the enormous changes Vygotsky helped make happen, that we have reverted somewhat to this idea that all knowledge must come from a child’s head alone. I’m thinking specifically about the nearly universally reviled standardized testing that has been proven to show nothing except maybe how good the student is at taking tests.

But enough soap boxing. Zones of proximal development are pretty neat. Here is a nice definition that is fairly easy to understand:

“the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.”

My operational definition: The distance between what one can accomplish with guidance vs. what one can accomplish alone. Why is this significant? Because it undermines most of what grounds education today. The smartest kid isn’t necessarily the one who remembers the most or masters what ze has been taught. The smartest kid is the one who can face a problem until ze has ever encountered, and use the tools around ze to accomplish it. That’s some Apollo 13 shit, and if I may say, a much more useful way to think about education.

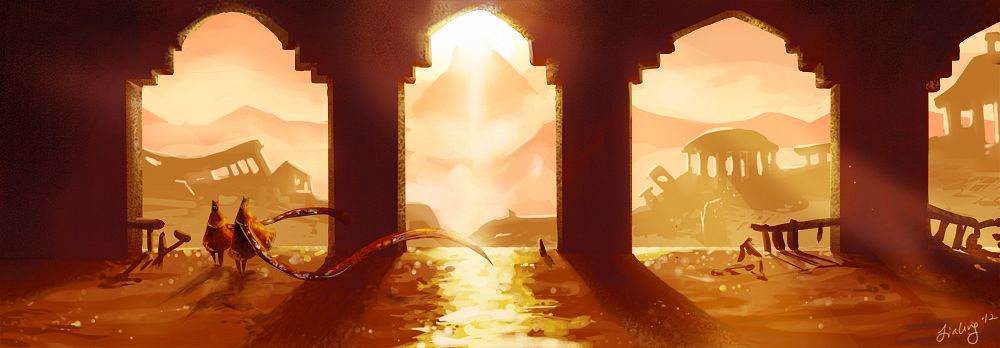

The Witness exists entirely in the Zone of Proximal Development. You rely on environmental clues for assistance, not peers or directions. The scaffolding is not a means to an end, but the scaffolding is the game: the aesthetics, the panels, the clues, the entire game is one big ZPD. Let’s contrast that to other games for a sec. I played 7 Days to Die last night on the PS4 to try out the couch co-op playability (it’s ok). In 7 Days you are constantly discovering new skills, abilities, and things you didn’t know you could do. But you aren’t learning. There is nothing about the environment that helps you intuit things. For example, you have to punch a tree to get wood, something that is absolutely crucial to lasting more than a day in the game. Unless you read it somewhere, saw it somewhere, or just accidentally swung at a tree, you could play that game for hours and not know one of the single most crucial things. There is a beginning quest telling you that you need wood, but while surrounded by trees and logs and planks on the ground, it certainly seems like there would be a different way to get wood than punching a tree.

The Witness on the other hand has an environment that exists in the ZPD. Everything means something, from paths to the colors of trees, to the angle of the sun. While you do need to make some guesses on which path to take or what to do next, the game will almost always guide you to the right spot for your ability, though you may get frustrated if you happened on a zone that requires knowledge that you haven’t gained yet. This is where the learning in the game gets really interesting, and where we can pivot to another educationalist, Jean Piaget.

Piaget, Vygotsky’s contemporary, conducted the first qualitative studies examining how children develop and learn.

“To Piaget, cognitive development was a progressive reorganization of mental processes as a result of biological maturation and environmental experience. Children construct an understanding of the world around them, then experience discrepancies between what they already know and what they discover in their environment.”

Indeed, The Witness puts the player in the role of Piaget’s child. Players do not have the knowledge to beat the game or exist in the world without exploration, trial and error, and learning to read the environment and act accordingly. A player cannot skip steps and still have the knowledge necessary to beat the game. Of course, it is unlikely that Jonathan Blow knew of Piaget’s work on how children learn and deliberately put the player into that roll. However, much of what we know about learning is indebted to his ideas, likely subconsciously finding their way into minds of developers and games. In other words, the way the game forces you into the role of a child who is first experiencing the world is likely no accident. Neither is why that technique is so successful.

These are just two of the folks (and probably the most boring) we built our Well Played on. I hope to have even more exciting stuff to report back once the conference is over.