This holiday weekend was one of the first times my daughter and I had to just relax and spend time alone since the beginning of the school year a month ago, so when she asked if we could stay home and write/plan/make a Minecraft machinima (like all good nerdlings), I was ecstatic. One of the things that she asked if we could be while we wrote our script and picked the skins for each scene we were writing was to turn on one of her favorite YouTubers for background noise. We chose to watch him play a game that we had already completed so that it wouldn’t be too much of a distraction, but the fact that the game was decision based still kept it interesting.

As we worked and listened I heard the YouTuber say something to the effect of “This will be all good as long as this pet doesn’t die.” And as the day progressed and the video droned on, the YouTuber made constant reference to the pet wanting to keep it safe, wondering why it was always walking with someone else, and being angry when the pet was mistreated by other in-game characters. All the time I kept saying to myself, “This is not going to end well.” Because I knew, I knew what would happened to the pet and I had seen firsthand what happens when the person in charge of keeping that pet safe takes that job seriously. And sure enough, when that moment came and the pet passed over the Rainbow Bridge our host was heartbroken. He threw his pricey headset, cursed, and even cried. For about 10 red eyed, sniffly minutes he just kept saying “That’s the one gawd-damned thing I said better not happen!” He had been charged with one task for that pet and he had failed. The choices that he had made had led him to this moment. At least so he thought, in that moment. And that’s what the game wanted him to think and to feel.

In her book How Games Move Us: Emotion By Design, Katherine Isbister talks about how the choices that we make in games

To the human brain, playing a game is more like running a race than watching a film or reading a short story about a race. When I run, I make a series of choices about actions I will make that might affect whether I win. I feel a sense of mastery or failure depending on whether I successfully execute the actions in the ways I intended. My emotions ebb and flow as I make these choices and see what happens as a result. I feel a sense of consequence and responsibility for my choices. In the end I am to blame for the outcomes, because they arise from my own actions.

And it’s easy to see how we can feel that much closer to the characters that we actively engage with in choice based games when we feel that our interactions with them are the result of the choices that we have made and that our very relationship is based on an amalgam of those choices. In this way these relationships seem to be, at first blush, much like the relationships that we have with our friends and animals in the real world. But what gets left out of this equation is the fact that these choices and interactions are coded by another. That we may be having little to no effect on these relationships after all.

And it’s easy to see how we can feel that much closer to the characters that we actively engage with in choice based games when we feel that our interactions with them are the result of the choices that we have made and that our very relationship is based on an amalgam of those choices. In this way these relationships seem to be, at first blush, much like the relationships that we have with our friends and animals in the real world. But what gets left out of this equation is the fact that these choices and interactions are coded by another. That we may be having little to no effect on these relationships after all.

In some cases we may be able to determine whether or not a young woman takes her own life, but we can’t (for example) determine whether or not she takes the life of another instead because the game is not coded that way. And in more extreme circumstances no matter what choices you make the outcome will be the same, but they will perhaps be talked about differently (or not at all). In the end all of these thoughts about choices and consequences just get lost in the heat of the moment, in the flow. And that state of flow is the goal of the well designed game. To make the “game” disappear and to make the experience flow in such a way that the experience becomes a part of our reality that let’s us engage with it on an emotional level. To feel said experience. In the same book, Isbister goes on to talk about the power of flow theory in games.

Flow theory has been a boon to the game design and research communities, moving discussion of what players feel and why away from the vague, if positive, notion of “fun” and into more nuanced emotional territory that can be shaped through design choices. When players discuss the emotions they feel when playing games, much of their vocabulary relates to flow (curiosity, excitement, challenge, elation, or triumph) or the lack thereof (frustration, confusion, discouragement). Thus, flow theory offers a useful lens for understanding the unique emotional power of games compared to other media.

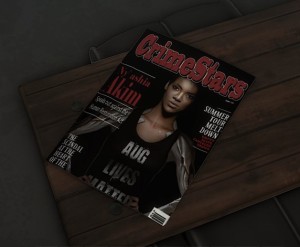

And ever the harbinger of doom, I am compelled to consider not only the favorable possibilities of choice, connection, and flow theory in games in terms of making us feel connected to characters in ways that heightens our engagement, but also in the possibility of the damage that can be caused by negative characterizations of of people or situations in games. If we are so invested in a game’s characters that we become emotionally attached what happens if, for example, the character of color that you feel a sense of connection to turns out to be severely misrepresented. This has the potential to not only disappoint (as in the shallowly represented case of Deus Ex: Mankind Divided and Augs Lives Matter), but to initiate a kind of grieving at the “death” of a character’s potential and the representation of self in the case of players of color.

And ever the harbinger of doom, I am compelled to consider not only the favorable possibilities of choice, connection, and flow theory in games in terms of making us feel connected to characters in ways that heightens our engagement, but also in the possibility of the damage that can be caused by negative characterizations of of people or situations in games. If we are so invested in a game’s characters that we become emotionally attached what happens if, for example, the character of color that you feel a sense of connection to turns out to be severely misrepresented. This has the potential to not only disappoint (as in the shallowly represented case of Deus Ex: Mankind Divided and Augs Lives Matter), but to initiate a kind of grieving at the “death” of a character’s potential and the representation of self in the case of players of color.

If game designers are going to actively pursue game flow that makes game experiences more realistic, more emotional, then they must also pay much closer attention to the content, characterization, and representation contained within those experiences. In this case it becomes more than just financial prospects, but an ethic of care as well.