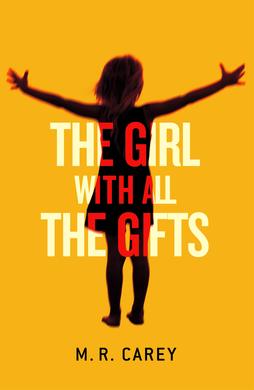

Last week, a friend mentioned the recently released film The Girl With All the Gifts, and its associated book. I’d never heard of either, but it’s no surprise to anyone around here that I’m a huge zombie nerd, so the trailer immediately caught my attention, because it’s a human story touched with action and violence, rather than the other way around. That kind is always my favorite, so over the weekend, I read the book. It’s a quick read, intense and devastating, with a lot to consider in terms of the larger zombie genre, and how games fit into that.

Mild spoilers ahead for M.R. Carey’s book The Girl With All the Gifts, but nothing much the movie trailer wouldn’t reveal.

Mild spoilers ahead for M.R. Carey’s book The Girl With All the Gifts, but nothing much the movie trailer wouldn’t reveal.

In Carey’s novel, the main character is a pseudo zombie, one of a group of children captured as test subjects, because while they react strongly to the smell of uninfected humans (and that smell activates their overpowering feeding sense), they do not appear zombie-like in any way, but rather as simple children, albeit children confined to wheelchairs fitted with straps that restrict their every move. Their environment is in every way artificial; they don’t enjoy freedom of movement most of the time, they don’t eat normally, they have no families, no connections, and the humans in their lives are treated with a chemical that blocks any smell that might trigger their more visceral reactions. In this way, they are made safe, and they spend their weekdays in a classroom, another artificial environment, learning about a world that no longer exists, so that their reactions, behaviors, and physiology might be studied in the hopes of finding a cure for the global infection.

Stories from the point of view of the undead are growing more common, but here, the children do not much understand what they are, or why they are; they only know their routines, and though that life is very different from what they hear in storybooks in the classroom, well, so is everything else. We know, though, and that knowledge is a driving tension as we journey with Melanie, the ten-year-old protagonist, as she begins to discover who she is and what that means for her and the people in her life.

Because game design is never very far from my mind, I kept asking myself how Melanie’s story might be rendered as a game, particularly since it is built around such a strong arc of self-discovery, agency, and power. Melanie doesn’t necessarily grow in strength throughout the novel, but in awareness, but either is a familiar trajectory for gamers accustomed to leveling up and gaining new thresholds of power and control. What’s interesting, though, is that we learn that Melanie can control her reactions to the human smell (and so perhaps can all the not-zombies like her)… but before she learns, Melanie, when presented with that tantalizing odor, is consumed by it. It becomes her entire being, until she learns to partition herself, to box it away.

Imagine how that might be rendered in a game space: you’re in a conversation with another character, and suddenly you can’t hear or think; the subtitles dissolve and you can only press X over and over again until you regain control, or else eat someone you might care about. Forget listening, thinking, concentrating; there is only the mastery of the hunger. The struggle not to survive, which is what we often get in zombie games — there’s a similar mechanic in State of Decay, in The Walking Dead, in Left 4 Dead — but a struggle to keep everyone around you alive. To keep your internal monsters at bay.

Often when we play as a character touched by the monstrous, we are given gifts. Special high jumps. Abilities. Extras. Bonuses. And Melanie has these naturally; she is strong, and fast (smart, too, but that seems to be her in herself, unrelated to her condition). It isn’t something she has to activate. What she has to activate is her humanity.

It’s a hard thing to consider. The zombie genre has a long history of demonstrating that humans are the monsters, and games here are no different; the “real” monster notion is explored in The Walking Dead, The Last of Us, Dying Light, Resident Evil, and on and on. We’ve spent less time considering that the monsters might still be human, and when we do, it’s sometimes played for melodrama or laughs. It’s extreme. Sometimes in movies — and in games — we are racing to preserve the human. Think Dead Rising 2 (and Dead Rising 3, too) with its Zombrex treatments, that struggle to hang on against the tide. It’s a direct metaphor, though of course, that’s what any surviving humans are doing in apocalyptic media: holding on. Struggling on.

Embodying the zombie, on the other hand, is often a mindless endeavor. It’s fun in Left 4 Dead multiplayer, say, but at the end of the day, it’s just kill, kill, kill (like many multiplayer experiences, really).

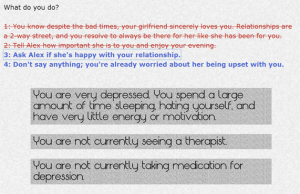

Perhaps because I’ve just played Firewatch, that very human story rendered exquisitely as a game, that I found myself craving this story experience in interactive form. I want to struggle and know the stakes are higher than they’ve ever been. To know that one slip of a sweaty thumb might mean death for someone integral. To know the right choice, but to be unable to make it. That’s one of the central ideas that draws me back to Depression Quest, when I think about what games can accomplish; I will never forget the first time I was confronted with a series of wrong choices, choices that were undoubtedly bad for me, while the right choices were visible, but unselectable. To know that I could not just win. That it wouldn’t be that easy. Instead, I would have to experience.

Perhaps because I’ve just played Firewatch, that very human story rendered exquisitely as a game, that I found myself craving this story experience in interactive form. I want to struggle and know the stakes are higher than they’ve ever been. To know that one slip of a sweaty thumb might mean death for someone integral. To know the right choice, but to be unable to make it. That’s one of the central ideas that draws me back to Depression Quest, when I think about what games can accomplish; I will never forget the first time I was confronted with a series of wrong choices, choices that were undoubtedly bad for me, while the right choices were visible, but unselectable. To know that I could not just win. That it wouldn’t be that easy. Instead, I would have to experience.

The Girl With All the Gifts is predictable, at times, because it’s a zombie story, because it’s an apocalyptic narrative, and I’ve experienced so many of those, and then suddenly it isn’t predictable anymore at all, and perhaps that’s what I want most of all — a game that will take me somewhere I’ve never been and can’t imagine. A game that will leave me there gasping in the dark, wondering what else I might have done. What other choices I might have made. Those are the experiences I remember. Those are the experiences that stay with me.