Late to the party, or valley, I plant crops months after everyone else. I water parsnips, consider sprinklers, plan optimal placement for trellises. I buy cows. I resisted Stardew Valley for so long, but now it’s the first place I go when I have a moment to myself. This game is all collecting, considering, planning, hoarding, money-making – why did I think I wouldn’t like it? Lately, this is almost all I enjoy in games: the meditation of compiling. I organize my chests. My little teal-haired avatar carries flowers through the valley. Quietly, I fish. The window of optimal fishing time is so short that it never feels repetitive.

I never played a Harvest Moon game outside of a few minutes in class, and never any other farming sim game. Nothing like this. I’m not sure why. I guess they seemed slow to me – the moving around, the collecting, the work of it. I hate work in games; it’s why I’ve skipped Animal Crossing, too. But there’s something compelling about Stardew Valley. Maybe all those other games would have compelled me, too, if I’d given them a chance. Maybe I just need to find this game at the right time in my life.

When I read that spouses would help with farm chores, I decided I needed to get married in Stardew Valley posthaste. Watering, after all, is the worst, and no one wants to do it alone, so I figured I’d romance Maru. I loved her mom, the carpenter, and her dad, who had an in-home lab for research. Maru herself was into gadgets and tech, and had a telescope, so I figured we’d get on fine. I didn’t pursue her actively, though; gifts and time are both at a premium when you’re in year one of your farm, just trying to make everything work. It wasn’t until winter when I got time to roam the town, really talking to people and learning about the other people who populated the valley, and it was then that I met Penny, Maru’s friend. Penny lives in a trailer with her mom, who seems, to put it roughly, to be the town drunk. Penny herself worked as a tutor for the town’s children; her room in the little trailer was full of books, though she seemed to spend as little time there as she could, choosing instead to wander under the trees when she wasn’t with the children.

She won my heart, but was I pursuing her or a past echo of myself? I couldn’t say. Didn’t want to think about it. But as our virtual friendship developed, some of the unique moments with Penny felt pulled from my own young adulthood. Too close to home, almost uncomfortably so, but it just made me more determined to get her out of there. The only option the game offers for that is marriage, so I’ll marry her.

Once decided, I read about the unique events with the other potential spouses. I figured I wouldn’t play through a second time, not with an endless game like this, so might as well spoil myself. I started with the characters I didn’t have much interest in – Haley, Alex, Sam. Haley seemed boring; I was right, I felt, but there are plenty of people who want something light in their lives, something straightforward and simple. There aren’t many people who can provide that. Maybe Haley speaks to that, and maybe I’m spending too much time trying to justify the personality of a game character. Sam struck me as the same. Alex, though, surprised me; here was someone more than he appeared, who struggled with wanting to be more than he had been so far, who was worried that he would never be enough. I read Leah, Abigail, Emily, Sebastian. Harvey. Shane. Everyone has some other dimension to them, some struggle, some desire. Care went into crafting these narratives, and maybe some are built on tropes, on the obvious, there’s something there worth connecting with, something to help soothe a troubled soul.

Sometimes, any kind of connection can help. Sometimes we all need a little connection. I imagine myself at fourteen, sixteen, twenty, playing this game. How it would have made me feel. How it would have helped.

I talk to Penny again, who finds joy in the sound of the rain on the roof of her trailer. Again, and she is worried about her mother, who doesn’t take care of herself. I think of my father, dead now for years. I think of the times I wanted to say what she’s saying, and I didn’t. How I kept it in. I imagine myself at twenty-five, playing this game. How it would have been a relief.

There is a meditation in watering virtual plants. I would do the same with real plants, but I always kill them. Here, too, in Stardew Valley, a few die each season, and I’m never sure why. This, at least, feels familiar. This is expected. I buy cows, chickens, goats; they like me, but never enough.

This, too, is expected.

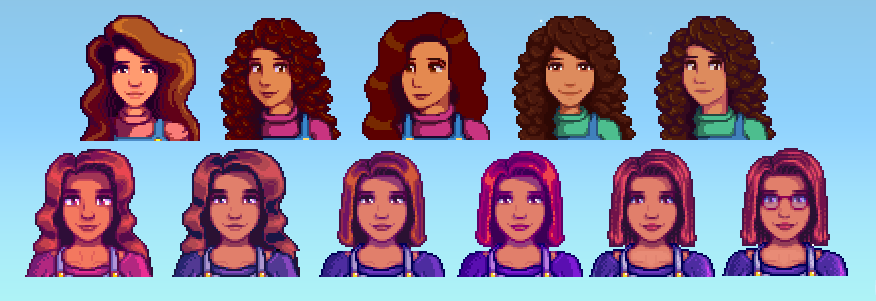

I look up the characters to see how they changed during development. The changing art is a surprise. I wish they’d gone for the longer-haired Maru, with the curls, the one who looked darker. I didn’t realize at first that the game’s Maru is biracial, but her ambiguous brownness was too much for some people; there are mods to turn her white. Her father, Demetrius, was lightened in another mod; a respondent complained that he was still just too Black. Other players in other places responded by turning everyone into Demetrius. Now it’s Demetrius Valley.

We all have our ways of coping, I guess, including the people who fear even virtual Black folks. Another player says she appreciates the lighter Demetrius because she’s tired of the Black man/white woman trope of the relationship. Even our intersections have intersections. Feelings are complicated.

Someone else makes a mod in response, and then Robin is Black. Other mods change more characters, introducing new races, new bodies, new identities. The game shifts, changing at need; players answer players and provide new and different ways for everyone to find some comfort.

This is community. There are good times and bad.

I make friends with Linus, who lives in a tent near the mines, who fishes leftovers out of the town’s trashcans. I explain to my son that his grandfather, too, lived rough, that from time to time he was homeless, that it isn’t so easy as setting up a tent and fishing the lake. What I don’t tell him was that my father skipped meals when there were none, so far as I know. I don’t think he dug through trashcans; he probably had too much pride, and anyway, a little bottle here and there was enough to sustain him. I tried never to think about it much. I did what I could for him, in the years before he died, after he got out of prison. I helped when he’d let me.

Sometimes I have to turn off the game and retreat back into myself. It’s not supposed to be heavy, I think. Less than simple, sure; an invitation for empathy and consideration, yes. But perhaps not this affective. It’s just a happy little farming game. Collect eggs. Make jam. But the stories linger. Shane, who struggles with his mental health. Kent, the returned soldier. And Penny, always Penny, at least for me.

It’s a happy place, but it isn’t pure, or simple, unless you want it to be. Unless you ignore everything else. That, too, is an option. It’s as good as any other.

This piece was written for Critical Distance’s Blogs of the Round Table feature for January on Healing.

One thought on “Growing Strong in Stardew Valley”

Something about the Harvest Moon games always spoke to me as a young queer rural kid: the duality of the meditation of the virtual farm coupled with the realities of the real farm dying around me. Our little town, its local economy, closed up shop in 1977 and moved to town. Nostalgic for something that was an unkind environment for so many. I want an unhavable past.

In my own trailer, there was the first boy whom I bared myself. We used to stay up late and make up our dream Harvest Moons: the clothes, the shops, making jam even. We dreamed of the relationships they could have.