I’ve always appreciated games that operate under a simple premise. Anything that involves solving a puzzle or accomplishing a simple task appeals to the part of my brain that was solidly addicted to playing Tetris on my Gameboy Pocket when I was ten, always striving to reach the next level, surpass the next obstacle, and solve what seems unsolvable.

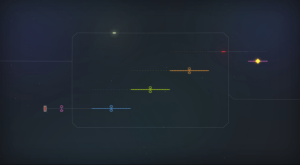

When I sat down to play a power hour of Linelight, an indie game created by Brett Taylor, I found quickly that my designated hour would stretch into three or four. The concept of the game is elegant in its simplicity: you control a small bar of white light that moves along a designated track to complete a circuit. Sometimes completing that circuit requires navigating around obstacles, avoiding the destructive red lights, and flipping switches, and other times the completion of that circuit involves attending to and controlling multiple elements. Even with progressive complexity, Linelight’s core premise shines through, literally, as each sub-level involves the basic elements of lights, tracks, and switches.

What I find most intriguing about Linelight is the way each world progresses in terms of mental scaffolding. As with most puzzle games, Linelight teaches the player as they progress, each level adding more complex elements to solve. The first world, for example, involves solving puzzles while avoiding coming into contact with the red light bars, which kill the player’s white bar on contact. However, about halfway through the first world, the white bar of light you control suddenly finds an ally: a pale red bar of light that works with you to navigate obstacles. The game shifts, repurposing a previously introduced element to work with the player instead of against them as they work to progress to the end of the circuit.

This repurposing adds an additional dimension to a simple puzzle game, playing with context in a way most games don’t. Turning an element initially introduced as an enemy into an ally requires players to adjust their expectations and their style in the middle of the game, making the increase in difficulty a question of adjusting playstyle rather than simply adding more obstacles in incremental steps.

The accomplishment Linelight makes here is managing to introduce this paradigm shift in the style of play while never breaking the game’s flow, something central to the experience it’s trying to emulate. Each sub-level is seamlessly connected to the one before it along a winding circuit, making it entirely possible for a player to move from the beginning of one world to the end without ever having to pause. Its mechanics like this that led to me staying up until three in the morning playing through dozens of levels without stopping, feeling like I was so deeply ‘in the zone’ that there was no way I could stop.

Each of Linelight’s worlds follows this pattern of introducing a play element and then adjusting it to create a kind of simulated co-operative style. While the first world repurposes the glowing red bars, the second world introduces the element of orange bars and only move when the player moves their white bar. While not under as much autonomous control as the player’s primary piece, it’s possible to operate amongst the orange bars in a more controlled fashion, requiring a different strategy from the first world. Once again, an introduced mechanic rapidly becomes something different, as you find an ally in an orange bar that operates under partial player control, changing the circumstances to create an allied mechanic from a previously antagonistic one.

Linelight does a phenomenal job of keeping the player interested by introducing new elements and shifting them around enough in a way that requires cognitive action, giving players puzzles on the surface while also encouraging them to frequently readjust, to reassess and recontextualize their path forward. It’s not uncommon for indie games to create new takes on old mechanics and concepts, but the places where Linelight succeeds are in the simplicity of its design. Color is used sparingly but with purpose, highlighting switches and identifying obstacles. The background music is lively but also calming, a simple piano track that loops continuously even during a pause.

Everything about Linelight is designed to keep the game moving forward, to help players remain in the zone even as they must adapt and adjust to new situations. All games operate under principles of flow to some degree, but finding the balance between complex puzzle solving and overly simplistic mechanics is a challenge any work in this genre has to overcome.

Linelight’s puzzles aren’t easy, but they are simple, often relying more on the complexity of timing and positioning instead of a ‘bigger is better principle’. Sometimes the puzzles are deceptive in their simplicity. I found myself stuck on a level that involved flipping a switch to move a red bar up a line on the circuit to remove an obstacle, one of the more minimal levels I had encountered thus far, but after a while I realized that I’d been overthinking it, trying to flip the switch myself when all I needed to do was let the moving red line do the work for me. Sometimes the challenge in a puzzle game is not that the puzzle is difficult, it’s that we overthink the level and expect it to be difficult when it just requires a shift in perspective.

The goal of a power hour review is to give myself, and readers, a taste of the style and gameplay of the title in question, and in a way I expressed my views of Linelight’s playability and quality simply through the fact that I found a power hour turning into a power trio. I talked about the benefits of incremental goals and gaming with pauses last week, but I think Linelight fulfills the itch I get in my brain for the kind of game I can really lose myself in the flow of, something simple but still engaging that gives my brain some exercise.

Linelight is available via Steam and PS4 on January 31st. Check out the game’s website here for more information.