I’ve written about my old undergraduate pastime of playing Dungeons and Dragons before, though working towards a PhD has made time a precious commodity I can rarely spend on social gaming. I did get the chance to do a little tabletop gaming over winter break, and, as it always does, rolling dice and hanging out with my friends made me nostalgic for the nights of sleep deprivation and chaos I’d spent playing D&D back in the day. Lately, in the wake of loud arguments on the internet and the news about morality, violence, and what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, the nostalgia is tinted with a level of pensiveness I don’t usually dedicate to my past, bringing to mind the way morality systems played out around the table with my friends as we let our wizards and fighters through fantastical stories.

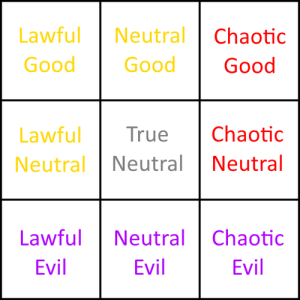

D&D 3.5, the version I learned on, makes use of an alignment system to determine a character’s moral compass. Denoted on an axis of Law to Chaos and Good to Evil, players can choose from nine varieties of morality to guide their character’s actions. The Player’s Handbook has a useful blurb defining what each of the alignments entails in terms of behavior and worldview, with players and Dungeon Masters free to adhere to them as loosely or as strictly as they see fit. Some character classes in the game require players to be a certain alignment, such as Paladins being restricted to the Lawful Good alignment and Druids needing to be Neutral on at least one axis, and those mechanics are specifically tied to the standard D&D universe, where gods also exist along those moral axes, offering benefits to (and raining vengeance upon) the characters who move through the story. Since D&D often acts as more of a game template for tabletop players, these rules are not set in stone, but a seasoned player knows exactly what to expect from a character referring to themselves as ‘Lawful Good’, because the game has a system for that, much in the same way it has a system for powers, weapons, and advancement.

Most of the games I’ve played have leaned more on the lax side of these systems, each alignment functioning more as a kind of horoscope or Hogwarts House than an actual dictation of actions. We operate within the basic game world functions of Law and Chaos and Good and Evil, but our DM’s reaction to us straying a little too far towards the other end of the access is minimal, or often nonexistent. For example, an evil-aligned character stopping to save a fellow party member from an ambush of kobolds, while not a particularly evil action, doesn’t instantly flip that character to the opposite alignment. This has not been the case in other games I’ve played, where any evil character performing an action closer to a different alignment would result in loud hours-long arguments about the morality system the game set in place and the importance of adhering to the rules. Many D&D players prefer to make stringent use of the alignment system, the nine-category grid a useful organization system to help them dictate how to interact with a world they can see in black and white. Alignment essentially puts characters into neat boxes that dictate to the players and the DM what they can expect from moral interactions: A Lawful Good character will save orphans in a burning building, a Chaotic Evil character will be the one setting the building on fire, and so on.

D&D’s alignment system has a lot in common with other morality systems in games, such as Mass Effect or Bioshock, which tend to have clear black and white extremes that reward or punish players for their actions depending on which side of the scale they fall down on. Alex has written about this several times and I think that it’s a topic worth revisiting in the wake of the current political climate, especially in the discussion of the most effective forms of resistance and action.

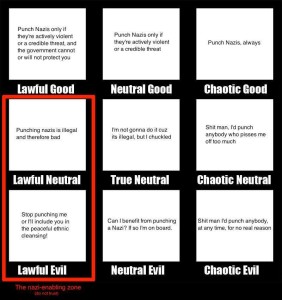

Ever since alt-right spokesman Richard Spencer earned himself a punch in the face on camera, the discourse both on and off the internet has heavily revolved around that singular act. Spencer’s assailant has prompted virulent arguments regarding the ethics of the incident, and of other acts of violence in the face of a regime that threatens oppressed groups. Examining whether or not punching a nazi (and yeah, Spencer is a nazi) is right or wrong has taken up more of my time over the last few weeks than I’ll comfortably admit, but the discussion always takes something of an absolutist turn, where a person agreeing with the action or encouraging further action of the sort is immediately placed into a set category: this person condones violence, this person is amoral, this person is dangerous and not to be trusted. Likewise, the people arguing against violent acts are painted as complicit, or as alt-righters themselves. Discussions of the ethics of punching a nazi in the face almost always end with a strong division between sides, where people are either on the side of right or the side of wrong, depending on each side’s perspective.

Morality is more complex than checks in boxes, no matter what games want us to believe. Nine categories of moral alignment are still categories, even if they’re more flexible than a sliding scale of kissing puppies or kicking them. Examining the ethics of violence against supremacists is going to take more than describing oneself as Lawful Good or Chaotic Evil, will be more nuanced than simply taking sides or throwing accusations. My expressing satisfaction and appreciation of Richard Spencer getting punched in the face doesn’t mean that I want to personally go punch anyone who disagrees with me, or that I think violence is the answer for everything we encounter as we enact forms of resistance. What it does mean is that when we talk about the morality and ethics of violence and protest, we need to remember that not everyone operates within the same moral systems as us, and people are more complex than Paragon or Renegade, than Chaos or Law. Remembering that we’re all coming at this from different places is a good step towards us having a real conversation and actually making progress instead of getting caught up in the details and running in circles.

We’ve got a long uphill battle ahead of us. And there are more important things to do than argue about whether or not it’s about ethics in nazi punching.

This piece was written in loving memory of the victims of the Bowling Green Massacre. Donate to help the survivors here.