Video games give us the opportunity to explore some dark social and political ideas in a relatively safe space and to learn a bit about ourselves in the process. Are we willing to kill Nazis, sacrifice children, or leave loved ones behind to discover secrets about ourselves (even if we may never see them again)? But a deeper question presents itself in this type of play? Does play trivialize these issues?

In their article “Exploring the Limits of Play: A Case Study of Representations of Nazism in Games”, Adam Chapman and Jonas Linderoth argue that

Another way to rekey a ludic frame whereby the tensions and conflicts between ludic meaning and everyday meaning can actually dodge critique is when it is overtly used as an artistic expression.

In other words, in games where the subject matter at hand might be in poor taste, adding an addition frame of understanding/critique can make it more acceptable as cultural or social critique rather than tasteless representations of sensitive situations in the name of “fun”. In the same way that I read the life of Franklin in Grand Theft Auto V as cultural critique only to find myself disappointed in (but not necessarily surprised by) the fact that some players completely missed what had been so obvious to me and instead saw Rockstar’s representation of “gangsta’ life” as authentic.

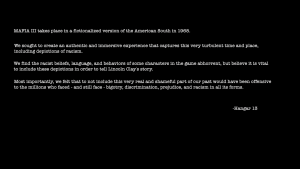

However, if we take a game with similar potential, in this case Mafia III, which includes the additional frame of not only the opening disclaimer by Hangar 13 which explains how racial epithets and historically accurate (but violent) situations have been used in the game, not solely for the sake of entertainment, but also as both a historical artifact and a statement on the treatment that marginalized people in the United States still find themselves subjected to.

However, if we take a game with similar potential, in this case Mafia III, which includes the additional frame of not only the opening disclaimer by Hangar 13 which explains how racial epithets and historically accurate (but violent) situations have been used in the game, not solely for the sake of entertainment, but also as both a historical artifact and a statement on the treatment that marginalized people in the United States still find themselves subjected to.

Chapman and Linderoth go on to assert that games have very specific opportunities to “upkey” the narrative in such a way as to save it being “just play”. In their article they write:

A third way in which a ludic frame can be rekeyed to avoid frame tension is by claiming simple historical accuracy, what Goffman refers to as a “documentary frame”. This rekeying works on the notion that topics are not chosen but simply found, in this case in the past. This utilizes a very particular (and, arguably, outdated) epistemological notion of what the practice of history is and thus denies the upkeying effect of representation. Instead, this rekeying seeks to narrow the perceived distance between the upkeying (history/representation, whether game, film, or book) and the primary framework (the past/the event, a framework that of course is generally only knowable through history). Indeed, Goffman was also sceptical of this and notes that paradoxically, even “what we have come to call documentary (tape, stills, or film) is exactly what should be suspect relative to standards of documentation”.

Mafia III also takes the opportunity to “rekey [it’s] ludic frame” (reframe what could be dismissed as meaningless play), in it’s documentary cinematic style. The story of Lincoln Clay and New Bordeaux is explicated via McCarthy hearing-esque cutscenes where other characters in the narrative tell their version of the story that we are currently playing through in an attempt to both “avoid frame tension” and call into question the nature and authenticity of their takes on Lincoln’s narrative that we see through Lincoln’s “eyes” in the gameplay itself. It is in this moment that we become Lincoln and our experiences become “real” These cinematics along with the historical montage of Civil Rights events that took place in the 1960s as Lincoln recuperates lends an air of authenticity and seriousness to Lincoln’s story and helps avoid criticism of the game as trivializing the horrors of racism and Jim Crow laws in the American South.

Mafia III also takes the opportunity to “rekey [it’s] ludic frame” (reframe what could be dismissed as meaningless play), in it’s documentary cinematic style. The story of Lincoln Clay and New Bordeaux is explicated via McCarthy hearing-esque cutscenes where other characters in the narrative tell their version of the story that we are currently playing through in an attempt to both “avoid frame tension” and call into question the nature and authenticity of their takes on Lincoln’s narrative that we see through Lincoln’s “eyes” in the gameplay itself. It is in this moment that we become Lincoln and our experiences become “real” These cinematics along with the historical montage of Civil Rights events that took place in the 1960s as Lincoln recuperates lends an air of authenticity and seriousness to Lincoln’s story and helps avoid criticism of the game as trivializing the horrors of racism and Jim Crow laws in the American South.

This week I’ve also been playing a lot of Guerrilla Games’ new release, Horizon Zero Dawn, and I started to think about how this game would measure up to a similar kind of rekeying of the ludic frame (if at all). Mechanically HZD is a solid game, it plays much better than almost every open world game that I’ve played over the course of the last year or so (especially Fallout 4 and Skyrim), but the blatant co-oping of the stories and culture of indigenous folks just rubs me the wrong way. It pulls me out of the story, not necessarily because it uses the customs and stories, but more so because it just doesn’t do it well. It doesn’t pay proper respect to the culture and offer insight into why things happen in the narrative instead of just trying to show how “savage” and unbending characters are. Things are done for no apparent reason. I allowed Pea to watch the opening cinematic with me and to help me play through the tutorial and one of the first questions she asked was “Why are they putting paint on their faces?” and that was the best question of the day, because this never got explained. It just gets assumed that it makes Aloy more “tribal”. I won’t go too far into HZD here, but there is definitely more discussion on that upcoming.

What it boils down to for Horizon Zero Dawn is that the rekeying of the ludic frame doesn’t stand up if there is no foundation upon which the rekeying to take place. In the case of Mafia III we have the history of racism and Jim Crow in the American South in the 1960s to serve as a basis, in Horizon we are left only with some amorphous cultural practices and myths that feel like the equivalent of your quirky old aunt showing up at Thanksgiving dinner in a “Sexy Squaw” costume dripping in fake turquoise necklaces in an attempt to “honor” indigenous peoples.

What it boils down to for Horizon Zero Dawn is that the rekeying of the ludic frame doesn’t stand up if there is no foundation upon which the rekeying to take place. In the case of Mafia III we have the history of racism and Jim Crow in the American South in the 1960s to serve as a basis, in Horizon we are left only with some amorphous cultural practices and myths that feel like the equivalent of your quirky old aunt showing up at Thanksgiving dinner in a “Sexy Squaw” costume dripping in fake turquoise necklaces in an attempt to “honor” indigenous peoples.