Last week, I was at an academic conference, presenting on a game I and a colleague created for classroom use. It’s a big conference, and I got to listen to a lot of very smart scholars hold forth on all the things I’m interested in, from first-year writing to games to tech comm to feminism and activism. It’s energizing to hear so many ideas, and in the last few days, my mind has been on overload with everything I heard and all it inspired. One question, though, has been nagging me particularly, because it’s one I kept hearing repeated, or an idea I heard referenced: the notion that GamerGate is over, that we’re in a post-GamerGate era.

These things aren’t the same, of course, and certainly one is more troubling than the other, and that’s the idea that GamerGate is “over.” How do we measure a movement that wasn’t a movement, an organization that wasn’t an organization, an era that wasn’t so much an era but an outgrowth of something else? We can find a specific origin here; we can unpack the particular ecologies it inspired—the flow of information from Eron Gjoni’s blog and outward, through moments like Internet Aristocrat’s accusatory video, through the GameJournoPros reporting and calls of collusion around the turn away from “gamer.” We know exactly when Adam Baldwin coined the term “GamerGate” and what was happening before, and after. But as I sat in a room with other academics and watched a slide flash with a beginning and end date for GamerGate… well, it stuck with me, that time marker. Who gets to say when GamerGate is over? Does a man get to say it, in the safety and comfort of a conference room in one of America’s weirdest, whitest cities?

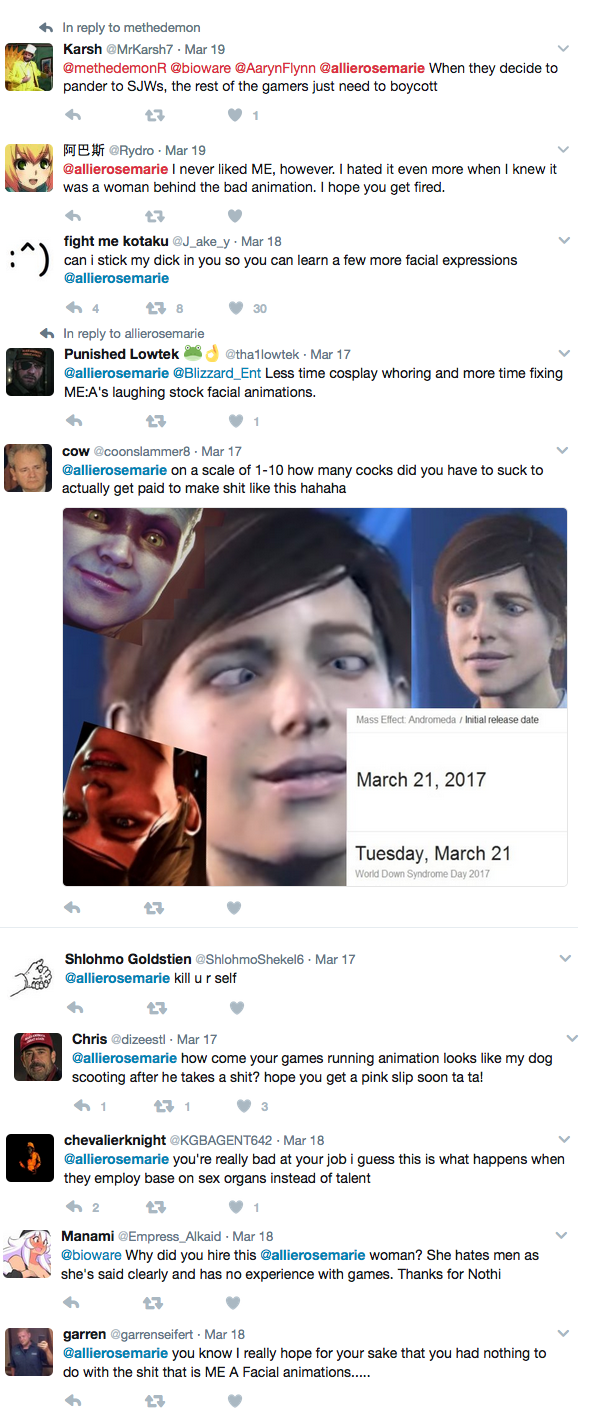

Allie Rose-Marie Leost could have a stake in this question, if we had thought to ask her. But we probably couldn’t have gotten through her Twitter mentions, on fire as they with angry Mass Effect players who decided to blame Andromeda’s facial animation debacle on her. Here’s a sampling of some of what happened after Leost was pegged as the sole person responsible for Andromeda’s facial animations (warning: large image, harassing language).

Is this incident totally unrelated to GamerGate because no one used the hashtag in those tweets? Is it over because that’s become less popular in social media harassment? Because plenty of commenters on the subreddit have said, oh, don’t harass Leost, that’s ridiculous — does that mean we’ve moved on?

Alternatively: is it not over because the subreddit is still going, because there are plenty of digital boltholes housing the people who were involved at various times over the years, and who are still involved in whatever this is now? Because there are many conversations about the Mass Effect “shitshow” that encourage this kind of behavior, purposeful or not? Because there are as many posters writing off harassment experienced by women in games spaces as just not that big a deal? Does that mean we are still in the same place we’ve been, or near it?

As I made the tweet collage, I sighed, because I’ve been here before. I’ve read all this; all that was different were the avatars and the usernames. Leost has had an outpouring of support, too, for which I’m grateful (I’m sure she probably is, too), and BioWare issued a statement denying she’s a rightful target, if target there is. But it doesn’t matter; when someone writes a targeted hitpiece, or a rumor begins, or a scrap of gossip goes wild, it’s blood in the water and the sharks are out.

Which leads us back to a more essential question then: What is GamerGate? What is it now? Over the years (sigh.), it’s been a lot of things. Is it the entitlement machine that took to social media to chase after Leost? Because that’s the foundation in this instance, isn’t it? Consumers who were so dissatisfied they had to vent their rage somewhere. We are displeased with this product, and we think we’ve found the reason; let’s get her. And even those who don’t participate in the “getting,” well, they’re still there, spreading information, rumor, scraps of this or that, playing armchair detective over possible collusion, second-guessing executive decisions at companies, and decrying media coverage.

This, too, is familiar; this was at the root of the Jennifer Hepler incident; it was a portion of the reasons Sarkeesian was targeted; it was at the heart of the arguments around GamerGate as consumer revolt. We are unhappy with these things, and we will attack, some with wallets, some with reddit posts, shared information, thunderclaps, and meme campaigns, and some? Well, some with this, and no amount of accusations of third-party trolling can really separate that which springs from the same source.

Is that GamerGate, then? The answer, I think, is complicated, neither a clean yes or no. It’d be easy to say yes, that what we’re seeing with Leost, that what we continue to see, is GamerGate and it isn’t over. But when I look at the shape of this thing we call GamerGate, when I look at the timelines and markers, those I’ve assembled and those assembled by others, I see the Maddy Myers/Samantha Allen incident just before before Eron Gjoni’s website went live. I see iterations of Depression Quest before that final release, and everything that came with it. I see so many moments, little stories, anecdotes from before the dominance of social media, stories of forums and games stores; I see women still, forever, asking for help in figuring out how to mask their voices so they can play online without anyone bothering them.

Is that GamerGate? How can it be, when so much predates anything we might associate with it?

And there’s another side of it: what about the people who post in the forums, in the subreddits, who tweet and comment, but who legitimately aren’t interested in the negative aspects that have been assigned to GamerGate? What of them? What is our responsibility to the different people who have come together under such a banner, knowing what it means? Do we tar them all with one brush? How do we break out groups that defy classification?

So the truth, then, lies somewhere else, and it can’t fit neatly between two dates on a PowerPoint slide. As scholars, we should do better than that, I think; our work should lie not in the dates, but in the nuance between and around. Nuance is a kind word for it, certainly, but not an ill-suited word. There are layers here to the behaviors of gaming and fan communities, and there always have been, for good and for not-so-good, and there’s little indicating any future change there, at least.

So, sure, if you want to say we’re in a post-GamerGate era, go ahead. Culture moves in stages, after all, and largely, the world has moved on to something new and different, an era of a more public alt-right, and a Breitbart executive standing at the US president’s elbow, to differently shaped Twitter debacles, related and not. We are somewhere, and history will surely have a name for it. But let’s not pretend the fallout from GamerGate is now so much detritus of the past, or pretend either that any of this started with a WordPress blog, a subreddit, or a hashtag. We work, of necessity, with human elements and human stories; we write about living ecologies and those affected within and around them. Let’s not be among those who forget about the impacts on those human stories, and the people who live them.

One thought on “The Problem of “Post-GamerGate””

very interesting post. When I followed the news around Allie Rose-Marie Leost I was asking myself the same: What are these people, do they belong to GamerGate? What has GamerGate been before? So hard to tell. But sure is that there is still an amount of people who are okay with bullying a certain person just because they are disappointed about a game. They even see it as “trophy” to be in the news now (I read through one of these user accounts above to see how they are reacting)