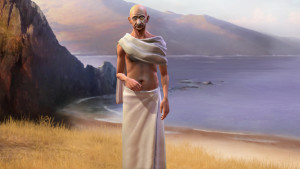

For me I think it all started with Civilization: Beyond Earth and by it I mean that colonialism saturation point with games. To be honest most games are tales of white saviors and colonialism, but that particular iteration of Civilization was one that I had been anxiously awaiting since it was first announced at on the game cons so I was just that much more disappointed. I thought that I was in for a whole new world, literally. After over a decade of playing the turn based strategy game and cursing the name of Gandhi at every turn, I was finally going to be able to take my political show on the road…or rather to space.

For me I think it all started with Civilization: Beyond Earth and by it I mean that colonialism saturation point with games. To be honest most games are tales of white saviors and colonialism, but that particular iteration of Civilization was one that I had been anxiously awaiting since it was first announced at on the game cons so I was just that much more disappointed. I thought that I was in for a whole new world, literally. After over a decade of playing the turn based strategy game and cursing the name of Gandhi at every turn, I was finally going to be able to take my political show on the road…or rather to space.

The first time I sat down to play was with Alex. We prepared ourselves for one of our multiplayer matches and as our ships landed on our new homeworld we quickly came to realize that something was amiss. Homeworlds that we had to establish because (as cliche as it sounds) we had already, for all intents and purposes, destroyed earth. We soon learned that the indigenous beings were not happy that we had “discovered” their planet and that they were attacking us was because we were invading their world and destroying the flora and fauna in order to build our own colonies. The whole scenario became even more disturbing when we discovered that if you killed “too many” of the beings the leaders of the other colonies would come on-screen and ask that you stop murdering them. That game disturbed me, and not in a good way. So while I had played 100s of hours of previous games in this series, I tapped out on Beyond Earth at less than 10. Willing colonization and genocide was just not something I was okay with doing.

and as our ships landed on our new homeworld we quickly came to realize that something was amiss. Homeworlds that we had to establish because (as cliche as it sounds) we had already, for all intents and purposes, destroyed earth. We soon learned that the indigenous beings were not happy that we had “discovered” their planet and that they were attacking us was because we were invading their world and destroying the flora and fauna in order to build our own colonies. The whole scenario became even more disturbing when we discovered that if you killed “too many” of the beings the leaders of the other colonies would come on-screen and ask that you stop murdering them. That game disturbed me, and not in a good way. So while I had played 100s of hours of previous games in this series, I tapped out on Beyond Earth at less than 10. Willing colonization and genocide was just not something I was okay with doing.

Considering all of this, when Dia Lacina’s piece, “Why I’m giving ‘Mass Effect: Andromeda’ A Hard Pass,” popped up last week I was able to understand where she was coming from to a certain extent. Much of who were are as humans helps us decide what is and isn’t tolerable to us, so when Lacina, as a Native woman, dropped a big old bucket of nope on Mass Effect: Andromeda mere moments into the game I could sympathize. (It’s my lived experience that makes the idea of Cuphead unbearable to me, but I don’t begrudge anyone else playing it if/when it actually releases.) My reaction to Mass Effect was a bit different, and some of the reason for this might be that 1. my cultural connection to colonization is not the same; 2. I was already a huge fan of the Mass Effect series; and 3. the rhetorical scholar in me could not help but to see where the game went after the marketing declared that players were going to have to “Fight for a new home”. I wanted to give Bioware the chance to make me (and other gamers playing) the chance to ask ourselves some incredibly hard questions about our ethical positioning and to see how they rewarded or punished us for those choices (or at the very least give me fodder for much rhetorical analysis).

[Danger light spoilers for the first 10-15 hours of the game ahead] At the time that I am writing this I have put just a little over 10 hours into the game in the last 2 days on top of the 10 hours that I played for the Early Access period. That’s not really much time at all, but some patterns seem to be unfolding for me. In the game, Bioware gives the player every opportunity to pay good lip service to anti-colonialism. As Pathfinder, Ryder declares that she understands why the game’s main antogonists, the Kett, are attacking them (before she learning that the Kett are not indigenous) because anyone would behave in the same way if aliens armed to the teeth invaded their planet. The choices (that are no longer tagged Renegade or Paragon, but rather emotional, logical, casual, professional…as if these things are separate and distinct) that you make allow you to verbally recognize that your very presence on the planet might be seen as an act of aggression and she acknowledges that we (as Pathfinder and team) are the aliens on this planet. So there is that, but I have to say that at this point I am not sure if that acknowledgement is going to make a bit of difference in terms of the future interaction with the actual indigenous flora and fauna.

[Danger light spoilers for the first 10-15 hours of the game ahead] At the time that I am writing this I have put just a little over 10 hours into the game in the last 2 days on top of the 10 hours that I played for the Early Access period. That’s not really much time at all, but some patterns seem to be unfolding for me. In the game, Bioware gives the player every opportunity to pay good lip service to anti-colonialism. As Pathfinder, Ryder declares that she understands why the game’s main antogonists, the Kett, are attacking them (before she learning that the Kett are not indigenous) because anyone would behave in the same way if aliens armed to the teeth invaded their planet. The choices (that are no longer tagged Renegade or Paragon, but rather emotional, logical, casual, professional…as if these things are separate and distinct) that you make allow you to verbally recognize that your very presence on the planet might be seen as an act of aggression and she acknowledges that we (as Pathfinder and team) are the aliens on this planet. So there is that, but I have to say that at this point I am not sure if that acknowledgement is going to make a bit of difference in terms of the future interaction with the actual indigenous flora and fauna.

In addition to the instance mentioned above, Ryder, at a point, makes it unequivocally clear that she and her party are explorers and not an army, but as we are well aware, exploration is often the precursor to (or an excuse for) colonization and genocide. In her article “Playing at Colonization: Interpreting Imaginary Landscapes in the Video Game Tropico,” Shoshana Magnet makes the argument that the very use and positioning of the map used to navigate the exploration is so value laden that colonization is embedded into the game before any choices are even made by the player.

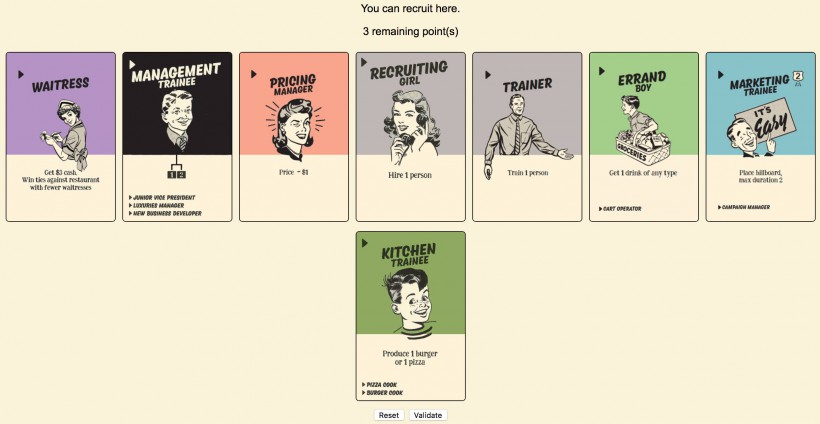

Maps are a language of value-laden symbols—a language that has spoken most often of “colonization and conquering” (Harley, 1988, p. 278). This trend continues in Tropico. The game begins with the opening of a map on the wall of your/presidente’s office. It is through this map that you choose the game you would like to play, including the level of difficulty. When you are actually playing the game a highly simplified map of Tropico is made available in the lower left-hand corner of your screen. As noted previously, players spatially navigate Tropico from above rather than from the point of view of the characters—as if the whole of Tropico were simply a map laid out before them (Lammes, 2004).

In the case of Mass Effect: Andromeda we are able to navigate the map of the potential homeworld planets from above and to choose our landing spots from that particular vantage point, but with this iteration of the game, unlike the previous three installments, you must land on the aforementioned planet and scan plants, animals, and other beings with your omni-tool. We are forced to see the destruction that has been heaped upon these planets first hand. This, in my opinion and experience so far, creates a connection between the player and the world that one might not otherwise be able to experience.

planets from above and to choose our landing spots from that particular vantage point, but with this iteration of the game, unlike the previous three installments, you must land on the aforementioned planet and scan plants, animals, and other beings with your omni-tool. We are forced to see the destruction that has been heaped upon these planets first hand. This, in my opinion and experience so far, creates a connection between the player and the world that one might not otherwise be able to experience.

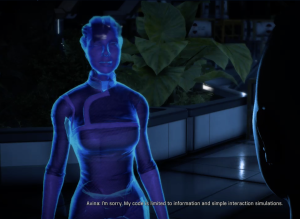

Because of my own experience with games like Beyond Earth and my sense of trepidation with Mass Effect : Andromeda this time around I find myself making carefully calculated decisions about what I say and what I do in-game. While I see that there is a specific need to protect the 20,000 or so people aboard our space station, I (as Ryder) also respect the fact that we are intruders on this planet and that we have an ethical (if not legal) duty of care while we are “visitors” in their system (as if there is ever any possibility or intention to go elsewhere). The most jarring part of my new “immigrant” experience has to be the interaction that I have with an AI upon arriving at the Nexus. The AI seems to be a little bit of everything that could ever possibly be wrong with colonization and the settling of a “new world”. Her pre-programmed responses reminds us that we are colonists and pioneers who are following our dreams, that language itself draws upon the nightmares that were Christopher Columbus and Little House on the Prairie where scores of Indigenous people were murdered by “innocent” explorers and colonists who simply wanted to settle their families and make their fortune. While Avina, the AI, is a nightmare wrapped in a hologram, one can only hope, based on the disarray that surrounds her, that she is supposed to be indicative of the fact that this line of thinking is both terribly flawed and extremely dangerous. Avina reads very much like a tour guide on the Mayflower and to take her at face value and continue on would feel too much like being complicit in the murder of scores of beings that were minding their own business before various aggressive aliens happened along and started killing things and destroying the environment.

Because of my own experience with games like Beyond Earth and my sense of trepidation with Mass Effect : Andromeda this time around I find myself making carefully calculated decisions about what I say and what I do in-game. While I see that there is a specific need to protect the 20,000 or so people aboard our space station, I (as Ryder) also respect the fact that we are intruders on this planet and that we have an ethical (if not legal) duty of care while we are “visitors” in their system (as if there is ever any possibility or intention to go elsewhere). The most jarring part of my new “immigrant” experience has to be the interaction that I have with an AI upon arriving at the Nexus. The AI seems to be a little bit of everything that could ever possibly be wrong with colonization and the settling of a “new world”. Her pre-programmed responses reminds us that we are colonists and pioneers who are following our dreams, that language itself draws upon the nightmares that were Christopher Columbus and Little House on the Prairie where scores of Indigenous people were murdered by “innocent” explorers and colonists who simply wanted to settle their families and make their fortune. While Avina, the AI, is a nightmare wrapped in a hologram, one can only hope, based on the disarray that surrounds her, that she is supposed to be indicative of the fact that this line of thinking is both terribly flawed and extremely dangerous. Avina reads very much like a tour guide on the Mayflower and to take her at face value and continue on would feel too much like being complicit in the murder of scores of beings that were minding their own business before various aggressive aliens happened along and started killing things and destroying the environment.

Even at this early stage of the game I am enjoying my time in Andromeda and I am anxious to see where the narrative goes next and whether or not the attention I am paying to making ethical decisions about the indigenous population will lead to more ethical treatment of them overall, or whether the narrative will simply progress in such a way that they will be collateral damage and meet the same fate no matter what I do. I am sure that over the next several weeks I will have a thing or two to say about that.