In the last few years, I’ve spent a lot of time considering so-called “walking simulators,” first as I dug into different definitions of games, and then, as I moved away from that, into perceptions of games and the experiences they offer. One of the games that comes up most often in discussions of walking simulators, for good or for ill, is Gone Home, an ambient adventure set entirely within the confines of a creepy house and the convoluted history of a family.

Last week, following up on an earlier controversy, I unpacked a little more ambient rhetoric and the reasons why I think exploratory adventures, walking simulators, and experiential narratives should be pulled together under that umbrella of the ambient adventure, but this week, I’d like to take a different tactic and explore Gone Home itself, as game and artifact, in an attempt to uncover a little of why this game in particular has inspired and continues to inspire such vehement reactions. Why is Gone Home such a perpetual touchstone for some, emblematic of all that is “wrong” with video games, and such an oft-used example of a “nongame?” Why do some other games that follow similar models (like The Stanley Parable) not get the same treatment? Is there a vast difference between them in terms of mechanics? Execution? Narrative? Or is there something else at work?

It’s important to look at the history of Gone Home and its release to understand the game, its treatment, and the idea of “walking simulators” in general. The formation of the Fullbright Company (now just Fullbright) was announced in 2012 along with Gone Home, their first game, and in the months that followed, the coverage was… interesting. Defensive, almost, in some cases, but certainly highlighting what was different about the game. Here are a few of the headlines:

- This Game Doesn’t Need Guns or Explosions to Make You Care. Just a House. (Kotaku)

- Gone Home: Forging Connections Without Characters (Polygon)

- Fullbright on the ’90s, How Many Guns Gone Home Has (RPS)

Others are just weird, like this from IGN: Gone Home Is Undiluted Adventure. Sure, in the very retro definition of (point and click) adventure games, this works, but—and maybe this is just me—”undiluted adventure” sounds like something we should pin on a game that at least allows the player to open the front door. And it’s true that even games that don’t need a shooting or combat element will sometimes shoehorn something in (I’m looking at you, Life Is Strange), because it’s a very traditional “game” thing to include. But the benefit of hindsight allows me to look back and see how the message of Gone Home as a different kind of experience was being pushed, and reactions in the comment sections (of these outlets, anyway), were by and large picking up what was getting laid down. People were tentatively excited. But there were some mixed reactions, too—people worried about the game as “pretentious,” or those who hoped there’d be puzzles or more interactive features. There was a lot of discussion of the game’s spooky look and feel. Expectations were coming together.

So then the game releases. Much acclaim. Many mixed reactions, too. As much as I re-read, though, it’s hard to put myself back into a years-ago mindset and really understand again the environment Gone Home debuted into, so I replayed the game’s opening. It’s been a long time, so I was somewhat fresh. I’d forgotten things, like the fact that you start on the enclosed porch and can’t leave. This creates boundaries—you will be in the house—and that’s good. It sets the stage. The game is communicating with you already. But let’s back up, because that’s hardly the first piece of information the player gets from starting up Gone Home. Here’s what happens upon starting a new game: the method of control is put up on the screen, and it’s simple—walk and look. That’s it. Everything falls under that, at least at first. This game, then, will be simple. You will walk. You will look at things. Once the controls disappear, the loading screen comes up, and it’s a cassette tape.

Now imagine a moment that it’s 2012 (preview) or 2013 (release), and you’re seeing this. Simple controls. Cassette tape. These are messages from the designer to the player, clues about the game to come, and Gone Home is telling the player that this is not set in contemporary times and it’s going to be a lo-fi experience. Don’t expect bells and whistles. This is a different experience and a different time. This is reinforced when the game proper begins with the playing of an answering machine message. and then the date. Gone Home does a great job here of telling the player exactly what to expect from what’s about to follow, but once the player is on that porch, with the closed door behind, and the flickering lights, and the sound of the rain, there’s a shift. I don’t want to call it a misstep, because it’s not. But there’s something very sinister in the air around the house, and it’s purposeful, but it might also be a mis-reading of a “typical” player, if there is such a thing.

Now imagine a moment that it’s 2012 (preview) or 2013 (release), and you’re seeing this. Simple controls. Cassette tape. These are messages from the designer to the player, clues about the game to come, and Gone Home is telling the player that this is not set in contemporary times and it’s going to be a lo-fi experience. Don’t expect bells and whistles. This is a different experience and a different time. This is reinforced when the game proper begins with the playing of an answering machine message. and then the date. Gone Home does a great job here of telling the player exactly what to expect from what’s about to follow, but once the player is on that porch, with the closed door behind, and the flickering lights, and the sound of the rain, there’s a shift. I don’t want to call it a misstep, because it’s not. But there’s something very sinister in the air around the house, and it’s purposeful, but it might also be a mis-reading of a “typical” player, if there is such a thing.

There’s an ominous quality to much of Gone Home. Dim lights, glow, corners, shady areas, some weird artifacts. There’s a sense of something about to happen. That something is what we’re most often accustomed to in game—the moment of action or reaction. Something happens, maybe an enemy, or a ghost, or a jump scare, or some other moment of crisis, and we solve it. It’s a problem, a puzzle. But there’s none of that in Gone Home. Instead there’s only the creeping realization of something lost that will never be found again. Oh, sure, the family might repair itself in time. But what’s lost is lost, period.

That’s sad. I’d even call it terrifying, in its own way. But it’s a quiet terror, because it’s human and for most of us, unavoidable in some fashion. Maybe we haven’t been through what’s happened in that house, for that family, but we’ve known sadness and disappointment. For its fans, this is where Gone Home shines. It’s resonant. We can say yes, that’s terrible, and I understand it. Something settles into place. For those who are still waiting for something else, who aren’t expecting that resonance to be all there is, I can see how it would be a terrible disappointment. I’m not sure Gone Home spends enough time establishing itself apart from those more traditional game cues of “flickering light=spooky=expect crisis!” The game trusts the player. Maybe too much, or maybe just trusting that players who wander in will be ready for what’s to come.

And that, I think, is the rift between fans and detractors. Expectation. Some of it comes from the buildup around Gone Home. Some from games themselves, and our history with them, because just as we can’t leave our emotions, reactions, humanity, and personhood at the door when we play a game, we can’t leave our history with games at the door, either. In a piece for Forbes last year, Erik Kain said something fascinating about Gone Home in particular that I think reinforces this idea:

I remember when Gone Home came out. A bunch of people contacted me about how terrible it was and how terrible it was that reviewers were lavishing it with such praise. It must be, I was told, because of the SJW politics in the game, because obviously nobody would enjoy a game that just has you walking around and not doing much of anything.

Now, I’ll readily admit that Gone Home was not my cup of tea. I found it boring; my subjective reality is that I’m bored very easily, and have a wandering mind. Maybe even a touch of ADHD. I could never get into really slow, literary books either even though a part of me feels a bit guilty about this. And so I read Dragonlance and Hardy Boys as a kid, and then graduated to Game of Thrones and The Dresden Files as an adult. War and Peace remains unfinished.

To sum up: Gone Home requires close reading in a way that isn’t usually required or even expected in games, and while I’m using “reading” here in a rhetorical rather than literary sense, but it can be cross-applied. Gone Home wants the player to tread lightly, discovering and considering. Gone Home is primarily interested in asking the player to feel, and it’s doing this through objects used to construct stories.

Now, a contrast: The Stanley Parable. This, too, is a walking simulator, though it isn’t discussed with the same vehemence and often doesn’t even turn up in discussions of walking simulators (note: that anger is even referenced in Kain’s piece above). The tag is there on Steam, but it’s not one of the tags that shows up in the summary, as it does in Gone Home’s summary. It’s in some top walking sim lists, but no one seems to hate The Stanley Parable like they do Gone Home, or consider it a cancer killing video games or anything. This fascinates me, since The Stanley Parable (and Davey Wreden’s follow-up, The Beginner’s Guide, though that was less well-received despite being remarkably similar in many ways) is, more than anything else, an interactive essay about choice and control (and about games). Oh, certainly, the player can make choices and disrupt the narrative, but… there’s a response for that (and probably an ending), and the message continues. Everything’s been anticipated. Everything fits into the game’s message, even active disruption, because disruption is what the game’s all about.

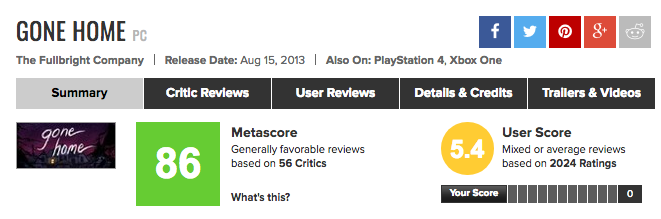

I love The Stanley Parable. I think it’s clever and I’m glad someone made it. But Gone Home is objectively better by every yardstick: better crafted, more detailed, even slightly better menus and controls (as much as those things matter in either game). There were simply more people with more resources working on it. Not that this matters—plenty of games that are the product of talented people working with piles of money don’t turn out half so memorable as either title—but it’s worth discussing when we look at something like this the aggregate Metacritic scores for both games:

I love The Stanley Parable. I think it’s clever and I’m glad someone made it. But Gone Home is objectively better by every yardstick: better crafted, more detailed, even slightly better menus and controls (as much as those things matter in either game). There were simply more people with more resources working on it. Not that this matters—plenty of games that are the product of talented people working with piles of money don’t turn out half so memorable as either title—but it’s worth discussing when we look at something like this the aggregate Metacritic scores for both games:

What a difference in those user scores. Despite the bonuses Gone Home enjoys due to how it was made, and the experience that went into it (Wreden didn’t have the experience Fullbright did; he was teaching himself, which is an impressive feat, considering what resulted), players apparently prefer Wreden’s game, which is also complained about less in terms of price point, despite the two games offering comparable experiences and, potentially, investments of time (The Stanley Parable is $5 cheaper when the games are at full price). And yes, I’ll say they’re comparable, despite all the endings in the second coming of The Stanley Parable, because for all its endings, it’s still one cohesive “story” (essay), but that’s perhaps a topic for another day.

Here’s a possible angle then on difference in perceptions between the two: The Stanley Parable, despite all its similarities to Gone Home in terms of gameplay, approach, everything, is less surprising—or maybe startling, or unexpected could be a better word. Which feels backwards to say, because for me the anchor of Gone Home is human familiarity while The Stanley Parable reaches beyond into something surprising, surreal, and sometimes absurd, but bear with me for a second here. In terms of anticipating players, Wreden knew who and what he was dealing with. He understood expectations and played toward them, while as above, I think Gone Home did something much more surprising and different with expectations, resulting in an experiment that fell flat for some.

As I read these articles and discussion threads and more from 2012, 2013, and since, the debates around “walking simulators” narrative-heavy games come back to a few things. Games need challenges. If anyone can get to the ending without doing anything, it’s not a game. You have to be able to interact, to puzzle things out, to do something. This is a summary, but it’s recurring—we even see it when Ian Bogost shakes his head over What Remains of Edith Finch. In the case of these two games, I’ll argue that both actually do provide challenges and puzzles and opportunities to interact, and while certainly anyone can get to an ending in either one, each game offers its own difficulties along the way. It’s just the how that differs.

The Stanley Parable, once the first ending is discovered, invites a very game-ish race to get to other endings. To try other paths. This is active, and the game is constantly telling the player something, while Gone Home expects the player to fill some of that in on their own. Even The Stanley Parable itself doesn’t invite players to ruminate on themes or endings; the loading text declares the end is never the end is never the end is never the end and actual endings invite a reset, a re-do, another try. Do it again, the game tells the player, and see what happens. No waiting! Just experiment and don’t worry, because the narrator will always be there to talk about it. No need to fill anything in. But the focus is on doing, on trying and testing, on acting, not necessarily on consideration, despite consideration and choice as central components of the game’s theme. In Gone Home, however, consideration is all there is. Explorations have a single definite ending. You can replay, but to what point, unless you missed items? The family will always fall apart. Everything that has happened has already happened, and all that’s left is for character—and thus, player—to consider what comes next. There’s no retry. No do-over.

That’s dark, isn’t it? It’s final. And The Stanley Parable has its own finality, but the structure only invites the player to linger later, when all is said and done, and you’ve even hidden in the broom closet and gotten that ending. The challenge of The Stanley Parable is deciding whether to go along or to rebel, and when and how to decide at each juncture. Figuring out and testing boundaries. Can I jump to my death here? Won’t that be a twist! A restart—now what? Rinse and repeat. But Gone Home challenges the player in a different way. It’s not a race. There’s no reason to rush toward the ending, not once the player figures out that oh, it’s not that something really weird happened, it’s actually that something very normal happened. The rest is just, well, being present. Digging. Experiencing. Piecing the story together bit by bit. And the challenge in Gone Home? It’s the challenge of regret and loss.

It’s not for everyone. And there’s no reason why it should be, just as Kain said above.

There are some important points to consider here. First, in terms of scholarship, certainly, and if this is all any indication, in the mainstream, too: no one’s really decided what the boundaries around video games are. Sure, there are definitions, but also so many warring opinions and ideas of what a game is and isn’t, and those definitions are shifting as the medium shifts. As a smaller point of that: there’s dissent, too, over what constitutes interactivity in both the practical and theoretical sense. What’s it really mean to interact with a game? Do we really interact, or are we just choosing paths in a maze with a thin veneer of pseudo-interaction laid over everything?

So when we play, are we just interacting with ourselves, with our own expectations and experiences? Is that what lies at the heart of play? Is all this, various responses to two similar-yet-different games, just another reflection? At the risk of sliding toward solipsism, I’ll say that I think yes, but also no, because those expectations and experiences involve more than just the self; they are a patchwork of all we’ve connected with and into. The games we’ve played, the experiences we’ve had, the bodies we inhabit, the ways we see the world and yes, games too. It all matters, and it matters a hell of a lot more than a boundary around what games are and aren’t.