In the 50th year of the journal of College Composition and Communication, in 1999, Jacqueline Jones Royster and Jean C. Williams began their essay “History in the Spaces Left: African American Presence and Narratives of Composition Studies” with a statement they call aphoristic, but that remains an important reminder we must repeat again and again until it becomes ingrained in our collective conscience:

This essay begins with a statement that is fast becoming, if it is not already so, an aphorism: History is important, not just in terms of who writes it and what gets included or excluded, but also because history, by the very nature of its inscription as history, has social, political, and cultural consequences (563).

In scholarly work, history doesn’t mean only the history of the field, which is part of Royster and Williams’ focus in that essay, as they explore the creation of rhetoric and composition as a discipline. History for us also means the sprawling discourse of the discipline itself, along with who created it, and when, and how it was selected, promoted, disseminated, replicated, repeated. History in scholarship concerns itself with how knowledge is made, who makes it, and what is even considered knowledge in the first place.

Royster and Williams write, in that essay, of a history of rhetoric and composition studies that has often skipped over the African American experience, from ignoring HBCUs entirely in research and the way “the viewpoints of African Americans are typically invisible, or misrepresented, or dealt with either prescriptively, referentially, or by other techniques that in effect circumscribe their participation and achievements” (579), and the latter statement should ring uneasily familiar for games scholars. Games, from development and design to communities to mainstream writing to scholarship, have traditionally privileged not only certain intersecting identities, but even certain definitions, boundaries, and standards that exclude, overlook, and circumscribe those on the margins of the dominant groups. While we want to be careful not to appropriate the struggles of Black scholars for recognition, there’s a lot we can learn from critiques like Royster and Williams’, and from the foundations of critical race theory, as we look for ways into a more expansive view of games studies.

At this spring’s Critical Games Symposium in Irvine, Adrienne Shaw delivered a keynote entitled “Are we there yet? The future of critical game studies,” which I begged her to send after hearing so many glowing reviews of her discussions of intersectionality in games studies (thanks, Adrienne!). Shaw spoke along similar lines, addressing opportunities for new and dynamic work in games studies:

Despite being around for decades, game studies still has tons of space to grow. I do think that we need more (just fundamentally more) writing about race, class, religion, disability, nationality, non-binary gender, and masculinity in games. There are so many other axes of identity that we could be exploring as well as the intersections of these subject positions. There are entire areas of the world that are underrepresented in game studies. I’d like to see more and better games history. All of these though require game scholars generally be more flexible about the types of play and games they consider studying. We, like our industry, often jump to the new and exciting but that means we do not research the old and the mundane as much as we should. I think there is room in our field for all of this work to be done, but we need to support the people doing it.

Note, however, Shaw isn’t only discussing the idea of intersectionality as part of identity, but also intersecting knowledges, an idea touched upon in this segment that is expanded throughout the keynote. Games studies is built from so many disciplines, so many knowledges; it is already an intersection of ideas, practices, and theories, but so many of those may be expanded further by considering embodied experiences, gaps, and new angles.

We need feminist games studies. We need intersectional feminist game studies, we need to move beyond the standard citations and recognize the other scholars at the table, the scholars who bring unique and interesting voices to the ongoing discourse in and around games, and we need this approach to be mainstream, everywhere, the norm and standard—but until it is, we need to make space for it. We need spaces that allow new lenses to sharpen and focus on aspects of games studies we don’t always consider. We need new and different voices, voices that aren’t always simply drawing lines in the sand and enacting boundaries, but that are forging new paths into lands not yet discovered.

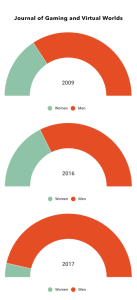

After a recent conversation with former EIC of First Person Scholar, Emma Vossen, about her talk at the Canadian Games Studies Association conference earlier this year, I took a look at several journals in games studies to get a sense of who was was being published—whose ideas were building the histories of games studies. I chose three journals in particular—Games Studies, Games and Culture, and the Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds—not only because they are important journals, but because they include easily accessible writers’ bios and I didn’t want make assumptions about anyone’s gender identity. Thus these stats I’ve compiled, from the first years of each journal, and the two most recent, address only pronouns provided by the authors. In a few cases, bios were missing pronouns, but I was able to locate bios for other publications that included pronouns. A few (a total of four, across all journals and all years) did not include pronouns in their bios and did not have bios at other journals or personal sites; I marked these as “indeterminate.”

The results (click any of the graphs to expand) are worth studying; by sheer numbers, women enjoy some representation in the journals as authors, sometimes mirroring even the 40% of gamers statistic promoted by the ESA. Sometimes women are much less present, but that seems to be an outlier. But that’s just the numbers; if we look at how many of those women are not first authors, if we were to exclude them (as an intellectual exercise; there’s no reason to diminish their work), the numbers drop dramatically. Moreover, if we were to collapse all repeated authors across gender identity, the numbers would swing dramatically in favor of the men. Later, I will prepare those numbers, and hope as well to dig into who is being cited in these articles, and to see if I can obtain data on race and ethnicity. At a glance, knowing as many scholars by name as I do, the numbers again shift dramatically in favor of white scholars—outside of special issues, at least.

What is most interesting to me from the data that is here, though, is that the numbers don’t much change through the years. Games and Culture shows an increase; the other two remain rather stagnate in terms of numbers, except in 2017 thus far, when women disappear from Gaming and Virtual Worlds.

So why are we stagnate in terms of representing a wider array of voices? The field of game studies is rife with scholars of all types. Women are responsible for some of the most robust, well known works in the field; we boast preeminent scholars of color writing from an array of fields; the field is rich with LGBTQ scholars. And yet one of the foremost voices in games studies can dance around the work of a female scholar without ever mentioning her or her work once—and in a major mainstream publication like The Atlantic, no less.

Games studies has a problem, but it’s not unique to our work; Royster and Williams saw it in rhetoric and composition, and Donna Haraway has been discussing it across the sciences for decades. Knowledge perpetuates itself, particularly once we begin privileging certain kinds of knowledges and experiences over others, and more so if we don’t consider the embodied context surrounding the knowledges we perpetuate.

So maybe it’s more accurate to say: yes, we need intersectional feminism in our games studies, but perhaps more, we need to recognize, promote, cite, and perpetuate the work already being done in that direction. As Shaw suggested in her keynote referenced above, we’ll stop reinventing the wheel and just roll forward, pulling more and more scholars onto the wagon, that we may ride together into a richer future.

This is our plan and purpose for the NYMG Journal of Feminist Games Studies. We run the risk of being pigeonholed in doing so—or should I say more pigeonholed, for many games scholars writing from and about gaming at the margins (of race, of class, of gender, of theory; name your margin) are already labeled as “only” scholars. Our own Drs. Samantha Blackmon and Kishonna Gray are proof of this; their writing is rich, nuanced, and about gaming, not “just” race in gaming, or “just” women in gaming, or just anything. Their work is about gaming; all gaming is gaming. So, yes, we expect that the NYMG journal will be slapped with a “just” by some. “Just” feminist gaming studies. But that perception is the limitation, not the work we do. In working to broaden the field, to build up new voices, to offer a home for pieces that may not fit elsewhere, we aren’t “just” promoting feminist work, but simply building knowledge, knowledge that our rich, interdisciplinary, ever-growing field needs to continue to develop in diverse, dynamic ways, just as the games we study develop similarly.

So what does feminist game studies look like? Certainly it’s not just publishing and citing a wider array of scholars from different background positions, though that’s one element. “One element” is the important language here: there are many ways to broaden the possibilities of the field, and being more acutely aware of authorship and position is only a small part of feminist approaches. Feminist methods like collaboration and the questioning of objectivity are another. This is why phrases like “identity politics” come off as so demeaning; there’s no divorcing identity from experience, so we are left with only politics everywhere. Certainly no one’s going to call Martin Heidegger feminist (and it’s not like we can leave Heidegger’s Nazi involvement out of the equation, either), but even in his building out of the concept of dasein, of being-there, Heidegger promotes the notion of inherent connections between selves and surroundings that we can ultimately link to systems created by selves and surroundings and worlds. We cannot divorce the self from surroundings or vice versa; identity is then always there, impacting everything, always. The issue, perhaps, comes when we think of some identities as more impactful than others. As Shaw said in her above-referenced keynote, “white, cisgender male, middle class gamers/developers/characters are intersectional identities as much as Black, transgender women, working class gamers/developers/characters are.” None of this can be divorced from any other element. The idea that one of those intersecting combination is more valuable, however, has arisen from its sheer prominence; feminist games studies asks that we all undertake an awareness of this and address it rather than simply ignore, accept, or perpetuate it.

In The Homesick Phone Book, Cynthia Haynes critiques a dependence on reason and the notion of conclusions, as though knowledge is ever final, divorced from context, or finished. While Haynes is writing specifically about writing, and about the teaching of writing, as we observe a field changing as quickly as new games are released, these too are good reminders of the possibilities of our future. We don’t know what feminist games studies can look like because we haven’t created all of it yet. Feminist games studies isn’t just about adopting a set of rules or ideas or methods—it’s about being open to the possibility of new and different perspectives, ideas, and approaches.

You can reach Alisha at her website.