While I have long been a fan and observer of cosplay and the cosplay community, it has only been two years since I have started to do cosplay myself and in that time I have cosplayed as Ezio Auditore, Korra, a female Loki, and a female Negan. The majority of the experiences I have had while cosplaying have been fantastic, but unfortunately as I “officially” entered the community I came to realize not everything about cosplay was as easy as I thought it was going to be.

I am not talking about the difficulty of constructing the costumes themselves, but rather some of the harassment I received at these conventions. When I was dressed as Ezio Auditore I was pulled into a 5 minute interrogation to determine my legitimacy as an Assassin’s Creed fan and as a gamer in general. When I dressed as a female Loki, which involved a top-fitted dress with a lower neckline, I noticed some people taking photos of me without my permission or trying to sneakily take a photo of my backside. Dressing as a female Negan resulted in whispers behind me about how Negan was not a woman and that I was only wearing the costume because it was popular. Ironically I even had some guys try to tell me simultaneously that I was a bad ass and that if I needed their help and protection around the con I should just ask them.

Sexual harassment and harassment in general towards women is not a new concept or experience for me, and I hope with the #MeToo campaign this is all the more abundantly clear to others as to the pervasiveness and seriousness of the issue. However, as someone new to the cosplay community I was already a little nervous dressing up, and as a fan excited to share my passion with others in a space dedicated to the acceptance and celebration of nerd culture, I was all the more shocked, uncomfortable, and angry at these moments. As I become more involved with cosplay and learn more about the culture I am both excited and dismayed at some of the attempts to help eliminate sexual harassment (and harassment in general) at cons.

The ban of booth babes seemed to be one of those attempts. At first glance, this ban was a step in the right direction. The use of booth babes, the intent to sell a game through a sexualized costume to emphasize women’s body parts, is sexist. However, the way in which they banned the use of booth babes, their word choice, and the way in which they enforce this rule is also partially sexist. Especially since this ban established a new grey area where companies can still hire professionals to help sell their game as long as these people have some knowledge about the game. The enforcement of this ban seems to be another way to police and monitor women.

This was illuminated when Jessica Nigri, a professional cosplayer, was asked to change her costume or leave the show floor at PAX 2012 where she was working a publisher’s booth wearing a Lollipop Chainsaw costume. Comments as to why they asked her change included what was “appropriate” attire and “unprofessionalism”. There are many women at the con that wear even more scantily clad costumes, yet this is not met with opposition in terms of con rules. By calling the professional cosplayer’s attire as “unprofessional” instead of pinning the blame on the publishers “unprofessional” actions, the fault is again on the women and this focus and these connotations delegitimize her as a fan and cosplayer. The publisher remains relatively unscathed and stagnant throughout this situation: They are never asked to leave, they are not embarrassed in front of a crowd, and they are not asked to simply add a variety of cosplayers to help sell the game.

As Nina Huntemann states in her article “Attention Whores and Ugly Nerds: Gender and Cosplay at the Game Con”, this is especially problematic when you consider how, “engagement in cosplay provides a pathway from player to producer that may empower young women, in particular, to pursue careers in the male-dominated game industry.”

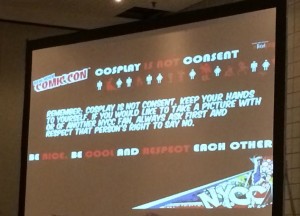

The campaign Cosplay is NOT Consent is another promising movement. It started at the 2014 New York Comic Con. Every year since then this convention has signs posted all over the show floor and they are even shown on screens before panels. New York Comic Con even has a page dedicated to describing sexual harassment. This movement is spreading to other conventions, but unfortunately is still missing from many or is not very prominent. San Diego Comic Con dedicates two sentences to harassment on their website and uses the very problematic definition of “common sense”. Blizzcon is even more generic. It is also difficult when many of the convention rules explain that if one experiences harassment or sees it happening they should report it. While a good practice, the issue here is that it puts the responsibility and pressure on those already being harassed, not the harassers. As Jennifer Dewinter and Carly Kocurek state in their article “Women and the Exclusionary Cultures of the Computer Game Complex”, “It’s not just that we need more women writing and speaking up about this; they are, and they are attacked.”

The campaign Cosplay is NOT Consent is another promising movement. It started at the 2014 New York Comic Con. Every year since then this convention has signs posted all over the show floor and they are even shown on screens before panels. New York Comic Con even has a page dedicated to describing sexual harassment. This movement is spreading to other conventions, but unfortunately is still missing from many or is not very prominent. San Diego Comic Con dedicates two sentences to harassment on their website and uses the very problematic definition of “common sense”. Blizzcon is even more generic. It is also difficult when many of the convention rules explain that if one experiences harassment or sees it happening they should report it. While a good practice, the issue here is that it puts the responsibility and pressure on those already being harassed, not the harassers. As Jennifer Dewinter and Carly Kocurek state in their article “Women and the Exclusionary Cultures of the Computer Game Complex”, “It’s not just that we need more women writing and speaking up about this; they are, and they are attacked.”

Cons have taken strides to reduce problematic situations by clarifying or adding harassment and sexual harassment policies. However, it seems that in trying to resolve some of these problems, cons have created new ones by enforcing subtle ways that put the blame or responsibility on women. These policies and actions further police the way women conduct themselves and all too often give others the opportunity to practice misogynistic ideals. On the other end the Cosplay is NOT Consent movement is a very promising campaign that many attendees state has made a difference at New York Comic Con. With 2018 approaching one can only hope this campaign gains more traction at other cons with as much popularity and enthusiasm.