Spoiler Warning: Ending details of The Wolf Among Us and side quests from Assassin’s Creed: Origins are discussed.

A few weeks ago my boyfriend bought the game Stellaris – a grand strategy space exploration game similar to Crusader Kings and Sid Meier’s Civilization. Together we made a race called the Furions, xenophilic fox-like creatures with a knack for science. Unfortunately, we were born into a galaxy full of xenophobic slavers. We declared war against the Empire of Hir’Qelli in the year 2130. With a larger fleet and better technology victory seemed certain.…

I don’t know what went wrong but after 300 years we are still fighting to free our people and every time we play our situation seems to get worse. We decided to start a new and hopefully happier campaign to play in between. While we were creating a new race, he asked “Who do you want to be?” and I stated, “Not the Hir’Qelli”. A few moments later I realized how ridiculous this was as the mammalians that embodied the Hir’Qelli only existed within that one galaxy and in that one playthrough. We could have made a race of these mammalians with the same stats as the Furions and only the picture portraying the aliens’ avatar, not the gameplay, would be affected.

I don’t know what went wrong but after 300 years we are still fighting to free our people and every time we play our situation seems to get worse. We decided to start a new and hopefully happier campaign to play in between. While we were creating a new race, he asked “Who do you want to be?” and I stated, “Not the Hir’Qelli”. A few moments later I realized how ridiculous this was as the mammalians that embodied the Hir’Qelli only existed within that one galaxy and in that one playthrough. We could have made a race of these mammalians with the same stats as the Furions and only the picture portraying the aliens’ avatar, not the gameplay, would be affected.

After that first playthrough whenever I see the anteater-influenced mammalian I also think of the Hir’Qelli. This one playthrough affected my behavior and feelings outside of the initial game. Even though the locations, species, and stories in Stellaris were made up I began to wonder how games could foster these ideas and how more relatable and realistic interpretations could affect players. After this I started to look for subtle ways prejudice was represented within the games I was playing – The Wolf Among Us and Assassin’s Creed: Origins – and how this prejudice could affect the player. To clarify, by ‘subtle’ I mean that the game does not largely focus on this issue within the game (i.e actually using words within the dialogue such as “prejudice”, “racist”, “homophobic” ect…) or there are many other “bigger and more important” issues taking both screen and game time (micromanaging and exploration in Stellaris, revenge and character upgrades in Assassin’s Creed: Origins, and solving the murder in The Wolf Among Us)

I started to ask myself the following questions: How are players given prejudicial information? How does their avatar absorb this information? How is the player given the means to respond to this information within the game? Who is creating these scenarios? And how are these scenarios beneficial or harmful to current attempts to diversify the industry?

How The Wolf Among Us Does It

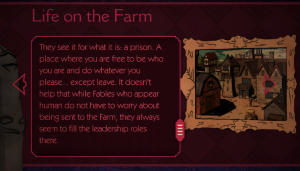

The Wolf Among Us explores the lives of fables – fairytales like the Big Bad Wolf, Snow White, and Beauty and the Beast, whom have come to live in Fabletown, a section of New York City circa 1986. Many are struggling to make ends meet in the ‘mundy’ world and must turn to corrupted individuals for help. Furthermore, there is a distinct rift between Fables that already appear human (or can transform into human at will) and those that need to buy glamours to change their appearance so as not to be discovered. Those that need to buy glamours are threatened with the possibility of being taken to The Farm, which many consider a prison.

It is described within the game’s Book of Fables (accessed at the main menu) that all governmental positions at the Farm are held by those with natural human appearances. This holds true within Fabletown too as all of the government positions have been held by Bigby (The Big Bad Wolf), Snow White, Blue Beard, and Ichabod Crane. It is unfortunate that the game only explicitly addresses this idea outside of the game.

That is just one way the game pushes aside prejudicial themes within the narrative. When it comes to interacting with ideas of prejudice and attempting to incorporate these ideas into gameplay the game does even worse. This done primarily through how Bigby and Snow White treat other characters and the narratives forced outcomes.

interacting with ideas of prejudice and attempting to incorporate these ideas into gameplay the game does even worse. This done primarily through how Bigby and Snow White treat other characters and the narratives forced outcomes.

There are times within the game that the player is given the opportunity to beat up other Fables that need glamours to hide themselves. This is problematic because you yourself are playing Bigby, a Fable with a great deal of privilege, as he can transform at ease and holds a governmental position (not to mention a white heterosexual male). Sometimes there is no way to avoid these violent acts as you either die or you just cannot progress. While allowing players the choice to perform racist, misogynistic, and homophobic acts in the first place can be problematic not allowing them to avoid these situations can be even more trying.

Many times there are no repercussions for Bigby’s actions other than a minor talking to, a sour face, and some cuts and bruises. Even when the games antagonist is caught and points out Bigby’s hypocrisy and harmful actions during the climax the writers and characters push this aside “to be dealt with later”. The cutscenes shown after the games climax do not indicate that any actions have been taken to ensure this.

There are also small moments that could have repercussions outside of the game. For example, at the very end one of the Fables, Toad, cannot afford to pay for glamours for his son and himself. They are shipped off to the Farm. The player is given options throughout the game to address how they feel about the Farm and glamours. No matter what the player does – even if they fight Snow White on multiple occasions, advocate the rights of Fables who need glamours, and give Toad money to pay for glamours – Toad is still taken away.

There are also small moments that could have repercussions outside of the game. For example, at the very end one of the Fables, Toad, cannot afford to pay for glamours for his son and himself. They are shipped off to the Farm. The player is given options throughout the game to address how they feel about the Farm and glamours. No matter what the player does – even if they fight Snow White on multiple occasions, advocate the rights of Fables who need glamours, and give Toad money to pay for glamours – Toad is still taken away.

This forced ending result could indicate to the player that fighting unjust or unfair systems is futile and further establishes those that need glamours as “lesser”. This is also concerning as Snow White too has a large amount of privilege and does not seem to empathize with Fables need for glamours at any point in the game nor tries to establish some sort of governmental system to help them after she takes office. She even goes so far as to threaten to take away the one affordable means of obtaining glamours. She has less field time than Bigby and in the end she chooses not to see the consequences of her actions and the emotional impact she is having on Fables by ignoring the ones she is sending away and refusing to see their send off.

How Assassins Creed: Origins Does It

AC: Origins takes place in Ancient Egypt during the Ptolemaic Period, an era of major political turmoil. Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII are fighting for the throne and Roman influence and culture has been fusing with the Egyptian landscape for around 250 years. This is predominately seen and felt in the north around cities like Alexandria. Though the two empires came to share some of the same gods, artistic styles, and ideologies, there was still tension between the groups. In this game prejudice between the Romans and Egyptians is clearly illustrated in the games passing conversations and side quests.

When Bayek, the games main protagonist, walks into the northern city Cyrene for the first time he makes a quick snide remark and explains with disdain how he cannot wait to see how “great” the city is. His sarcasm alludes towards feelings of angers that the Romans believe they are better and more erudite. Other dialogues include Romans and Egyptians calling each other “dogs” and the Romans often refer to Egyptian practices as barbaric or less sophisticated. It is common for this hostilities to erupt into violence that the player cannot avoid. Though I have not finished the game I have already encountered two side quests that implement this idea clearly.

In the sidequest The Weasel, Bayek is investigating an Egyptian woman’s murder. It turns out the murderer was a roman mercenary who said his intentions were not to kill her but to teach her a lesson for defying him. He calls her an “Egyptian dog” and then calls Bayek a “stupid Egyptian”. A fight ensues in which you must kill the mercenary in order to finish the quest.

In another side quest called Old Times you meet up with a longstanding friend Claridas, previously known as Sennefer, whom changed his name to appear more acceptable to the Romans. He too has changed his religious beliefs, attire, and occupation to match Roman culture, despite the fact that he admits that the “Romans look down on us”. After drinking too much the two start to argue. One of the points they argue revolves around Roman influence within Egypt. Bayek dislikes Claridas new lifestyle and Claridas becomes angry that Bayek quickly judges him without fully understanding his motivations. The two break out into a fist fight. The quest ends before either can die but the two end up parting on sour terms.

Though players are not given as much agency in how they respond to situations like in The Wolf Among Us the way information is given to the player and how their avatar absorbs this information is much different. AC: Origins takes on a more historic approach and despite the fact that the world is quite open the quests themselves are linear. Players are not allowed to customize their actions to respond to the prejudice Bayek sees or endures and his opinions are made clear to the player, not vice versa.

Though players are not given as much agency in how they respond to situations like in The Wolf Among Us the way information is given to the player and how their avatar absorbs this information is much different. AC: Origins takes on a more historic approach and despite the fact that the world is quite open the quests themselves are linear. Players are not allowed to customize their actions to respond to the prejudice Bayek sees or endures and his opinions are made clear to the player, not vice versa.

This is an important distinction and departs from the way many traditional historic texts around this period approach these subjects – that is the struggle of the natives are often ignored in light of the white mens triumphs. They revolved around Roman influence in Egypt and describe how cities, like Alexandria, flourished and ascribe the benefits of Egyptian lifestyle to increased trade and spreading intellectual ideas. Though they address the conflicts regarding the throne, most of it is confined to just that – royal conflict, and ignores the unrest and the persecution many Egyptians endured.

Despite Ubisoft’s character and historic liberties the game explores these prejudices and overall lends itself to a more educational experience. The game does not back down from these issues and the writers do not excuse prejudicial actions or try to delegitimize them. The player explores these happenings, not through a large amount of decision making and agency, but through discovering the world, investing in individuals’ stories and completing more quests. Showing these conflicts to the player in this unflinching manner, in which they are assuming the role and seeing the perspective of someone who is being persecuted, could teach players to have a deeper sympathetic nature and better understanding of prejudice and how it is harmful to everyone. The game lends itself to the idea that in order to understand people better you should listen to them and try understand their struggles.

Why It Matters

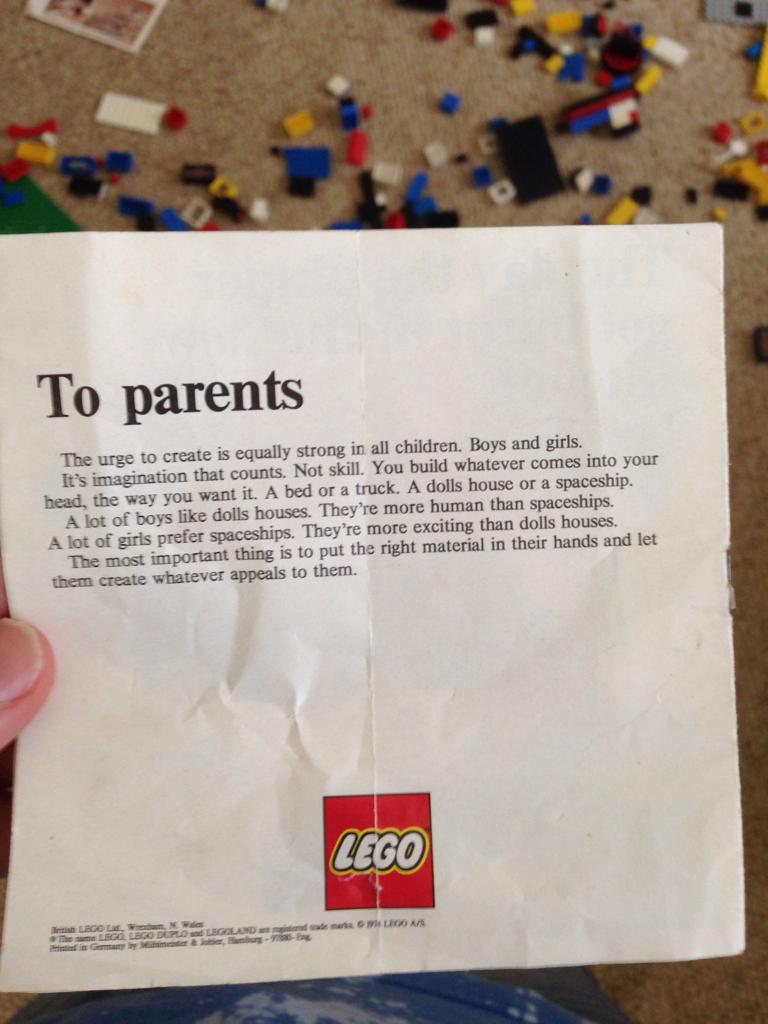

The importance of analyzing how a game establishes prejudice as a narrative component and how it allows players to interact with prejudice as a gameplay mechanic cannot be understated. As we advocate for better understandings within games developers and gamers must push beyond the notion that simply including ideas of diversity within games will be sufficient in the goal for improved representation. As Adrienne Shaw points out in her book Gaming at the Edge, “Games tend to provide diversity in a way that is marketable but not necessarily socially transformative. Indeed, games more than many other media manage to profit from making single text pluralistic without having to face the potential backlash of making it actually diverse….play spaces are also not inherently welcoming to all bodies. Games encourage and value certain types of player over others” (187).

The importance of this topic becomes more profound as new studies have actually shown that video games can promote collaboration and empathy between groups; can lower prejudice1. We need to be careful how and who are constructing these situations as they can promote gatekeeping practices and encourage hostile behavior. They also have potential to influence beneficial socially progressive impacts. They can be a means of constructive exploration and a means to push beyond ambivalent “it’s better than before” reactions. While The Wolf of Among Us is lacking in many areas AC: Origins seems to be a step in the right direction.