Content Warning: This post details sensitive and controversial topics that occur in Doki Doki Literature Club! It also contains plot and character spoilers.

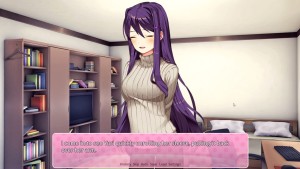

In my last post I went into detail on the unconventional gameplay of Team Salvato’s visual novel Doki Doki Literature Club!, while also mentioning the unexpected disclaimer that appears upon starting the game every single time: “This game is not suitable for children or those who are easily disturbed.” While part of this disclaimer is for the psychological horror aspects of the game, the disclaimer is mostly to warn players against the more dangerous elements portrayed, and that is the representation of depression, suicide, self-harm, and abuse.

Each of the three girls you can attempt to pursue have strong and unique personalities; however, in a more realistic twist not typically found in dating sims, they are all hiding various problems in their lives, both physical and mental. Subtle cues and dialogue lines between characters at the beginning of the game hint to what each girl is suffering from in their lives, and as the game progresses all of them begin to spiral downward and become more self-destructive. Monika, as a self-aware AI with no romantic path, is a special circumstance since she doesn’t exist in the same manner as the other girls, and as such will not be very prevalent in this article.

As the main character and the only boy in the Literature Club, you can choose which girl you want to spend the most time with and get to know better. Pursuing Natsuki or Yuri will reveal more about their home life and personal struggles, while your best friend Sayori’s internal conflicts are revealed gradually regardless. The three girls are vastly different from each other and embody various mental and physical health disorders and abuse that Dan Salvato has personally experienced in his life in some form. As the lead programmer, writer, and composer of Doki Doki Literature Club!, Salvato’s decision to infuse the writing and character personalities with events from his own life helps ground these subjects in reality more so than a writer trying to include controversial subjects for sake of simply having them.

Natsuki initially embodies a typical tsundere character, being very stern and critical to you throughout the game, occasionally lashing out physically. If you spend your days reading Manga with her under the window, you discover that her father is incredibly strict, to the point where she can’t have friends over and she hides her Manga at school. She will also occasionally pass out from hunger, and Monika informs you that her father doesn’t give her lunch money and doesn’t keep a lot of food at home. This knowledge is reinforced if you spend Sunday baking with her, as when it is time for dinner she will comment “when my dad cooks, I need to eat as much of it as I can…” It’s also implied (not so discretely) later in the game that Natsuki’s father is also physically abusive to her, and that the Literature Club is one of the few places she feels safe. A secret poem in the game files, presumably written by Natsuki, holds similar lines such as “I like it when papa cooks me dinner/gives me lunch money/doesn’t comment on my hobbies,” and eventually ends with the line “I like it when papa is too tired for anything…”

Natsuki initially embodies a typical tsundere character, being very stern and critical to you throughout the game, occasionally lashing out physically. If you spend your days reading Manga with her under the window, you discover that her father is incredibly strict, to the point where she can’t have friends over and she hides her Manga at school. She will also occasionally pass out from hunger, and Monika informs you that her father doesn’t give her lunch money and doesn’t keep a lot of food at home. This knowledge is reinforced if you spend Sunday baking with her, as when it is time for dinner she will comment “when my dad cooks, I need to eat as much of it as I can…” It’s also implied (not so discretely) later in the game that Natsuki’s father is also physically abusive to her, and that the Literature Club is one of the few places she feels safe. A secret poem in the game files, presumably written by Natsuki, holds similar lines such as “I like it when papa cooks me dinner/gives me lunch money/doesn’t comment on my hobbies,” and eventually ends with the line “I like it when papa is too tired for anything…”

Yuri is shown to be almost polar opposite to Natsuki’s personality upon first meeting both of them. She is incredibly shy and quiet, is very nervous when talking to people, and often second guesses herself or speaks without thinking and later regrets it. The depth of her self-harm is initially more subtle than Natsuki’s domestic abuse, but is eventually given more screen time due to the course of the game shifting Yuri’s personality to that of a yandere, who quickly becomes violently obsessed with you. The few cues given are that she is always seen wearing a long sleeve shirt even outside of school and that she has an extensive collection of knives which she finds beautiful. The only written text hinting to Yuri’s self-abuse before she is caught in the act later in the game is “I come in to see Yuri quickly unrolling her sleeve, pulling it back over her arm,” as well as a metaphorical poem titled “The Racoon,” which, when read with the knowledge that Yuri cuts herself, can easily lead one to discern what exactly she is writing about. Monika later leads you to believe that she doesn’t cut herself due to self-loathing or depression; rather, she gets an adrenaline high from it, though you are never explicitly told her reasoning behind her self-harm otherwise.

Yuri is shown to be almost polar opposite to Natsuki’s personality upon first meeting both of them. She is incredibly shy and quiet, is very nervous when talking to people, and often second guesses herself or speaks without thinking and later regrets it. The depth of her self-harm is initially more subtle than Natsuki’s domestic abuse, but is eventually given more screen time due to the course of the game shifting Yuri’s personality to that of a yandere, who quickly becomes violently obsessed with you. The few cues given are that she is always seen wearing a long sleeve shirt even outside of school and that she has an extensive collection of knives which she finds beautiful. The only written text hinting to Yuri’s self-abuse before she is caught in the act later in the game is “I come in to see Yuri quickly unrolling her sleeve, pulling it back over her arm,” as well as a metaphorical poem titled “The Racoon,” which, when read with the knowledge that Yuri cuts herself, can easily lead one to discern what exactly she is writing about. Monika later leads you to believe that she doesn’t cut herself due to self-loathing or depression; rather, she gets an adrenaline high from it, though you are never explicitly told her reasoning behind her self-harm otherwise.

Sayori is your character’s childhood friend, and as such she is the one you know best and the one that is simultaneously developed the most and least throughout the game. She is only present in the first act, but during that act her unending happiness and bubbly personality begins to crack, and she slowly seems acting more and more uncharacteristically downcast. There are small cues in her poems pointing to a mental disorder, often referencing the phrase “in my head” or “get out of my head.” Eventually you approach her over the weekend in her room where she reluctantly admits to you that she suffers from depression, and she has suffered from it for her entire life.

“I’ve always been like this. You’re just seeing it for the first time.”

Sayori appears to have a form of depression where she strives to keep all her friends happy in favor of neglecting her own happiness, stating “Why make other people put their energy and caring to waste by having them spend it on me?” and “It’s bittersweet when people try to care about me.” She also explains why she is always late to school, struggling to find a reason to get out of bed every single morning, and all initial attempts made by your character to try and console her are rejected.

Sayori appears to have a form of depression where she strives to keep all her friends happy in favor of neglecting her own happiness, stating “Why make other people put their energy and caring to waste by having them spend it on me?” and “It’s bittersweet when people try to care about me.” She also explains why she is always late to school, struggling to find a reason to get out of bed every single morning, and all initial attempts made by your character to try and console her are rejected.

Sayori’s confession comes as a shocking reveal to most players, and hits very close to home for some, as those who suffer from depression often hide it even from the ones they are closest to. Your character seems to respond in a fairly realistic sense, from a perspective of someone who can’t understand what their best friend is struggling from even though they desperately want to help. You can’t choose the dialogue that your character says in this section either, in turn making you feel even more helpless during the conversation. His initial anger in demanding to know why she never told him about her depression followed by his attempts to put more effort into caring for her happiness are met with tears and resistance from Sayori, who just wants things to continue as they have always been, refusing help from you.

The next day you return to Sayori’s house to find she has committed suicide by hanging herself.

Your character blames himself for not saying what she needed to hear and being too self-centered before the game abruptly ends for the first time. Simultaneously players are thrown into a stunned terror, both from the jarring reveal and the realization that everything your character said either didn’t help her at all or made her condition even worse. It is ultimately unclear whether her mental health would have deteriorated to the point of suicide so quickly had Monika not interfered with the game’s code, or if she would have grown so depressed to attempt suicide at all otherwise.

Doki Doki Literature Club! manages to pack an incredible amount of character depth into a visual novel that spans a few short hours for a complete playthrough, and while it isn’t perfect, it seems to be one of the more realistic and comprehensive representation of mental/physical disorders present in games. The severity of each of the girl’s struggles grow as Monika breaks the game’s code, and it does unfortunately begin to overplay Yuri and Natsuki’s physical abuse, but it is more difficult to determine whether Sayori would have still taken her own life had Monika let the game play out in a typical fashion. And because the game is so short while addressing multiple mental disorders and physical abuse, none of the three characters are given quite enough time to fully flesh out their entire personality to the breadth that they deserve.

DDLC! lays a strong groundwork for discussion on representation of these topics as well; I spoke to Jordyn about her opinions on them after watching her play through the game, and I’ve also read through several forums of other players discussing the various representations, particularly that of Sayori’s depression, and noted that some people strongly relate to what her character is struggling with while others feel the situation and dialogue was written completely wrong. And I think that’s where one of DDLC!’s strongest points lie; it naturally facilitates deep conversations between players and their thoughts on the game’s successes or failures.