(For those of you who did not read my last blog, this is part of my dissertation which focuses on a visual analysis of video game company policy. Obvs what I put forth in my diss is more nuanced and situated in academicy stuff, but this is more fun.) EA is comparable in size to Blizzard, and like Blizzard, EA has a fairly “stock” section on harassment.

Harassment has no place at EA. We do not tolerate sexual harassment or harassment based on gender, race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, pregnancy, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or family status, veteran status, medical condition, disability or political belief, whether it’s verbal, physical or visual harassment, or a form of retaliation for any complaint of harassment. (1)

They distinguish between equal opportunity and harassment, which shows an awareness that these things are separate issues.

However, this awareness is misguided. In their equal opportunity section, EA writes, “Electronic Arts values equality and meritocracy” (1). Emilio Castilla has shown that it is in environments that claim to be mericratic where women and minorities face the most discrimination. He finds that “Although these policies [mericratic ones) are often adopted in the hope of motivating employees and ensuring meritocracy, policies with limited transparency and accountability can actually increase ascriptive bias and reduce equity in the workplace” (1479). In this sense, we can except there to be even more problems with the discrimination and harassment of women and minorities in environments that claim to be mericractic towards them than a company who does not even acknowledge their existence.

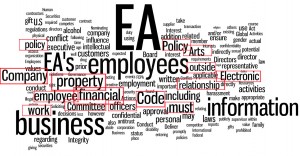

This holds up somewhat when analyzing the word frequency visualization. Like Blizzard, the most frequent words used are corporate words like EA, employees, business, and company. The medium level frequency analysis, however, shows a slightly different picture. In the figure below, the human is almost erased completely. Words like property, policy, financial, committee, code, and must dominate the middle level, showing a hyper-focus on policy and legal protection. So, while a hermeneutic analysis may suggest that EA is further advanced in terms of equality than Blizzard, we can see the opposite is likely. Instead, EA seems to hide behind buzzwords without actually showing any more care for women and minorities than a company who does not mention them at all.

This holds up somewhat when analyzing the word frequency visualization. Like Blizzard, the most frequent words used are corporate words like EA, employees, business, and company. The medium level frequency analysis, however, shows a slightly different picture. In the figure below, the human is almost erased completely. Words like property, policy, financial, committee, code, and must dominate the middle level, showing a hyper-focus on policy and legal protection. So, while a hermeneutic analysis may suggest that EA is further advanced in terms of equality than Blizzard, we can see the opposite is likely. Instead, EA seems to hide behind buzzwords without actually showing any more care for women and minorities than a company who does not mention them at all.

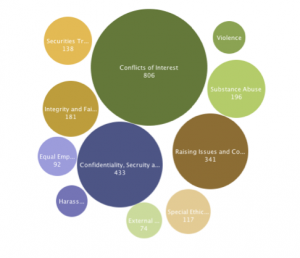

The bubble visualization paints a picture of EA that is similar to Blizzard. The largest section is the Conflict of Interest section, which focuses primarily on corporate espionage, soliciting EA employees, and contract work. The second largest section is confidentiality and security, which again deals with keeping corporate knowledge out of the public eye and out of the hands of rival companies. The third largest section, promisingly, is about how to go about raising issues with the code. While EA does say that it will provide waivers to the code if necessary (let’s hope they don’t wave the harassment section), they also provide a vaguely menacing threat about termination if the code is violated. To report this violation, however, the employee is supposed to find the “appropriate individual” to which the report should be made. As Castilla argues in his work, this type of lack of transparency is one of the biggest contributors to inequality in the workplace. It suggests that the code is really meant to protect those who are already on the inside of the community, not those attempting to break in.

EA’s reputation, and its growth, has been somewhat tumultuous in recent years. Despite growing by 15% in 2012, it grew -.55% in the past 3 years total. Their performance in the marketplace mimics this, with falling stocks and profits. EA was also voted the “Worst Company in America,”[1] with Forbes reporting that PR was the biggest reason for the company’s less than stellar performance. Of course, EA itself has spoken publicly that they do not believe sexism is the reason for the lack of women in the industry.[2] In fact, EA VP Gabrielle Toledano reports that “It’s easy to blame men for not creating an attractive work environment – but I think that’s a cop-out. If we want more women to work in games, we have to recognize that the problem isn’t sexism.” She does not seem to see a connection between the staggering rates of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and discrimination and the industry not being attractive to women. (I mean, hell, if I had a 1/3 chance of being sexually assault at work tomorrow, guess where I WOULDN’T be… guess where I would NEVER be again).

This may be an easy example of the connection between the view put forward by the company documents (ie. that if you are good enough, you will succeed) and the VP (we only don’t have more women because they aren’t here). However, I believe these two things are integrally related. Changing one may not directly change the other, but when a company decides that it wants to value and protect its diversity, then I have to imagine that positive change will follow.

One thought on “Analysis of EA’s Employee Code of Conduct”