Change is inherently a discursive project.

This means that change is restricted by the

structures of language and by the conventions

of language use. Change will be a product of

what can be legitimately said (or written)

in a specific context at a specific moment in time.

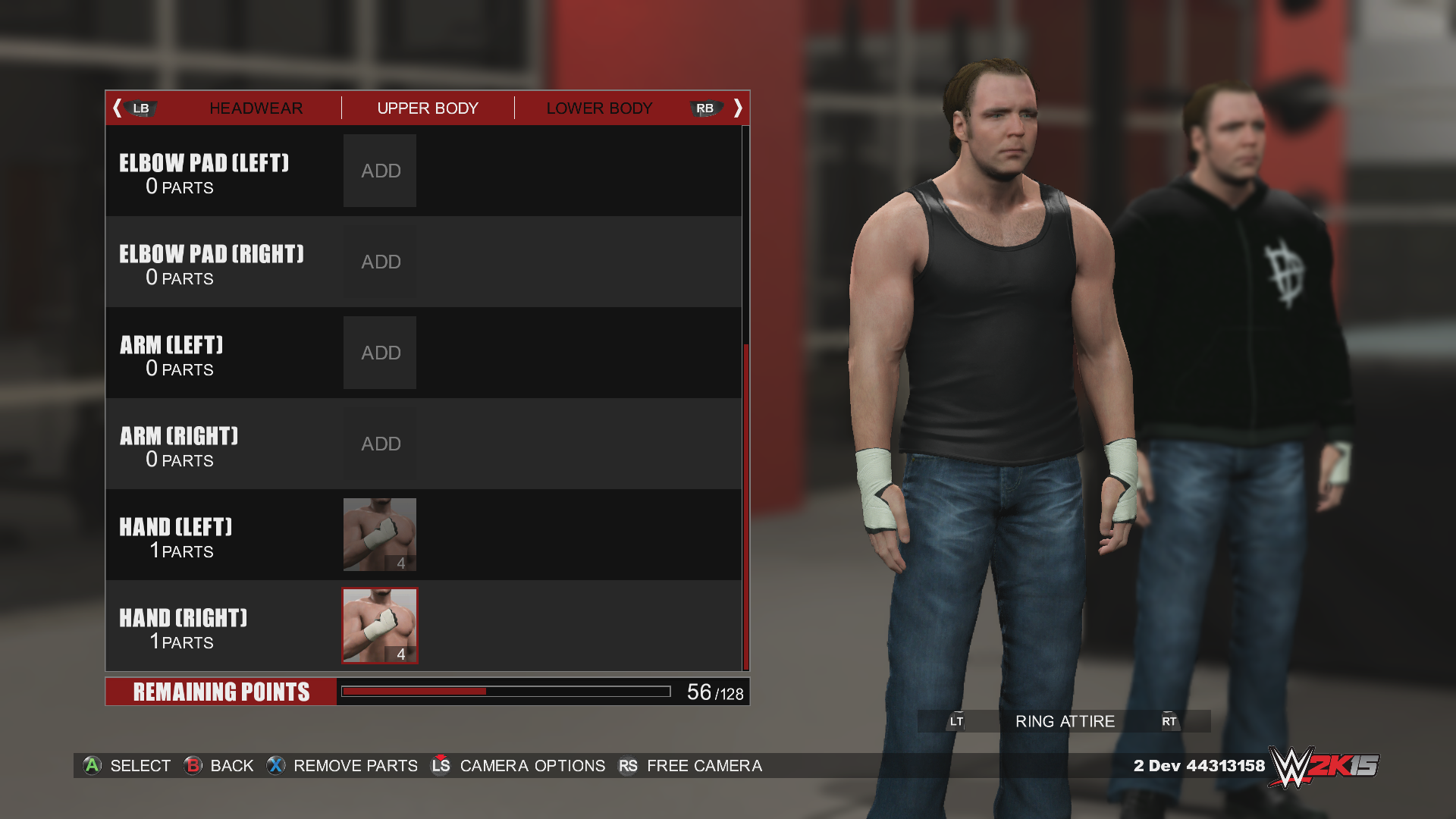

(For those of you who haven’t been following my posts, this is the sixth post in a series that analyzes the company policies of five video game companies: Blizzard, EA, Zynga, Riot, and Valve. These posts are all part of my dissertation and are somewhat taken out of context so that they are appropriate for the audience of NYMG. Rest assured, my actual chapter has far more of the boring academic stuff that makes it credible. For more detail on the policies, please see my previous posts. I have written this with the assumption that the readers are familiar with the policies of each company, as it comes on page 44 of my analysis chapter. However, I have attempted to repeat crucial details where necessary.)

Gender at Work, an organization dedicated to equality in the workplace, discusses their approach to workplace change in their report, “What is Gender at Work’s Approach to Gender Equality and Institutional Change.” They use a holistic approach to creating gender equality in the workplace, and they use a holistic approach when both analyzing extant workplaces and when actively pursuing change. For them, change is laid on two continuums that feature informal v. formal changes and individual change v. systemic change. The quadrant between formal and systemic change is workplace policies. In order to create change in this quadrant, Gender at Work reports that companies must at the very least have three things:

- “Mission includes gender equality”

- “Policies for antiharassment, work family arrangements, fair employment, etc”

- “Accountability mechanisms that hold the organization accountable to women clients” (3)

First, companies need to explicitly address gender equality. If there is no mention of gender equality in the formal documents, the possibility for equality in the other quadrants (access, consciousness, and internal culture) is severely limited. Then policies that represent issues that particularly affect women like maternity leave and harassment need to be explicit. Finally, formal systems of accountability need to be in place for when employee or customer rights are violated.

As we have seen in the workplace policies of the five video game companies analyzed above, these three items are rarely enacted. Riot is the only company that lays out a formal system of accountability for when an employee’s rights are violated. Policies about harassment and family concerns are varied from company to company, though Gender at Work’s holistic approach would likely find these all lacking. If the only harassment policy in the company is the bare minimum legal statement, it does not show that the company is truly devoted to equality or protecting female employees.

None of the five companies include gender equality in their mission statements. Zynga’s Mission Statement reads “At Zynga our mission is connecting the world through games.” Blizzard, on the other hand, has a more extensive mission statement that reflects eight core principles: 1) Gameplay first 2) Commit to quality 3) Play nice, play fair 4) Embrace your inner geek 5) Every voice matters 6) Think globally 7) Lead responsibly and 8) Learn and grow. This mission statement is interesting, at least in that several of these items could be seen as encompassing gender equality. However, gender is never mentioned explicitly. EA’s mission statement is much like Zynga: “We are an association of electronic artists who share a common goal. We want to fulfill the potential of personal computing.” EA, it seems, has no mission for the people of their organization or for their customers, but rather their obligation is to “personal computing.” Riot has five components to their mission statement: player experience first, challenge conventions, focus on talent and team, take play seriously, and stay hungry, stay humble. Like Blizzard, their mission is certainly interesting and leaves room for gender and equality to be important components, but it falls short of Gender at Work’s call for explicitness. Valve does not have a traditional mission statement, but it seems that “We’re always creating” is their key phrase found on their website and other company documents. None of these mission statements meet the first requirement laid out by Gender at Work for equitable workplace policies.

The lack of equitable policies is in and of itself a problem, but it is a larger problem for what it exposes about the deep culture of an organization. Gender at Work is interested at getting at the “deep structure” that they believe is responsible for much of the gender inequality in the workplace. This deep structure consists of four parts: political access, accountability systems, cultural systems, and cognitive structures. Examining policies is one way to expose and change the deep structure of a company. As we have seen throughout each stage of this analysis, the policies at these companies do not come close to reaching even the lowest standards of gender equality set by groups like Gender at Work. Until that part of the quadrant is stable, it is likely that little will change. We may not be able to directly change people’s cognitive beliefs about gender or the political access that women have in major tech-based companies, but policies is one way that we can indirectly change those things at the local level.

Also a side note: Next week will by my last post in this series. I will have an overview of all of my posts, as well as a biting conclusion for y’all. I’m looking forward to sharing it with you.

3 thoughts on “5 Video Game Companies: Textual Analysis of Workplace Policies pt. 2”

I think this work on policy is really important–particularly when we consider that, indeed, policies are a discursive infrastructure for decision-making. I’m curious to see more about the ways that something like “Every Voice Matters” might /not/ be seen as equitable: is this used as a cover up for inequitable policy? or, rather, does it function as an inactionable policy–how does a policy like this do the work women often need it to do? what are the processes tied to the edict every voice matters?

Can’t wait to read more, ALayne! Let me know if you need a set of eyes on any of the texts you’re working on. ~KMoore

To me, the “every voice matters” here serves a similar function as meritocratic claims do in these environments: they set up a systems that can function to exclude women and minorities under the guise of equality. In other words, they use equality as a kind of shield to hide behind. This seems even worse than saying nothing, because it 1) acknowledges that there should be more equality but 2) we don’t actually care about making things more equitable, but want to cash in on pretending like we are. Like Castilla talks about in his work on meritocracies, these things obscure discrimination. In a company like Blizzard that is constantly under fire for sexist, racist, homophobic stuff, they are using this statement (methinks) to avoid actually, oh I don’t know, hiring some women? That’s why the group I’m using in this section, Gender at Work, is so persistent that there needs to be transparency and that policies like this should be specific and explicit.

But, that’s my opinion. I don’t really know enough about what happens behind the scenes to say one way or the other. But it certainly smells funny to me. And Blizzard’s actions speak for themselves. Um, and yes, I would love to have you read some stuff! You may regret offering that!

I had to google what holistic meant. >.<

Some of those mission statements seemed pretty basic and blah, they definitely need to add allot more to them.

A biting conclusion, "you had my curiosity but now you have my attention".