As part of my dissertation work, I’m proposing a theory called Procedural Ethics, a hybrid of feminist research methodology, ethics, and procedural rhetoric. As ethics is currently growing in popularity in game studies, and feminist research methodology offers one of the most sensible and comprehensive strategies available, a hybrid methodology based in both areas will be both useful and timely. It is my hope that through Procedural Ethics, the field of video game studies will begin to redefine its primary goals of investigation. Procedural Ethics calls into question any theory of video games that does not consider social/cultural factors, even when studying things like algorithms. Likewise, Procedural Ethics asks researchers to consider non-human factors and their influence and agency in a particular situation, even when studying seemingly non-technological factors.

Defining Procedural Ethics, as with defining any term, is necessarily reductive, particularly because it is a key component of Procedural Ethics that it is emergent and context-dependent. However, it does have what I consider to be fundamental characteristics dependent on the context, history, and emergence of game studies. In other STEM fields, these characteristics may emerge in a slightly different way. First, Procedural Ethics suggests that it is unethical to exclude cultural factors from any investigation of the technological. The second characteristic is that it is fundamentally interdisciplinary. Finally, it also requires the researcher to include her values and beliefs as part of the study, and she must acknowledge how these beliefs shaped each part of the research from what questions were asked to how answers were interpreted. More on this in another post, however.

What I want to talk about in this post is how people in game studies are currently talking about ethics. There are four scholars talking about ethics each in a different way, at least from what I’ve found: Miquel Sicart, Matt McCormick, Bonnie Nardi, and Mia Consalvo. They help paint the story from which Procedural Ethics is beginning to emerge.

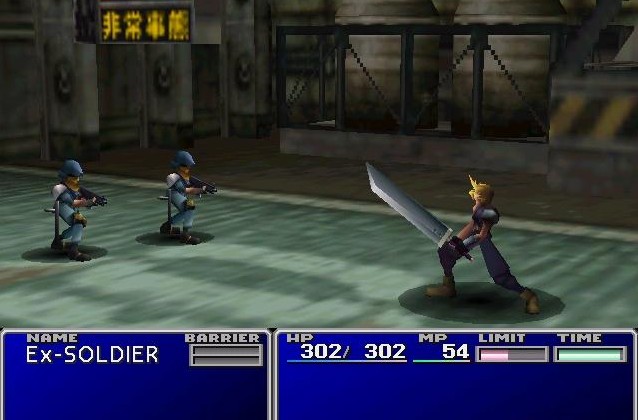

Miguel Sicart, an Assistant Professor at the Center for Computer Game Research, writes about the ethics of playing and designing games in his 2009 MIT Press book The Ethics of Computer Games. Sicart’s book is an indication of the rising interest in video game ethics as an analytical model. Sicart calls his work “an academic exploration of ethical gameplay, ethical game design, and the presence of computer games in our moral universe” (2). Sicart situates his work between the field of applied computer ethics and the few articles and books that have been written about ethics in the field of video game studies. What Sicart adds to the literature is a focus on the relationship of the player and the game as a designed system. Sicart attempts to uncover some of the complexity of the way the player and the game interact and the way each component interacts with outside components (like the video game designers or the video game community). The primary interaction Sicart sees as being ethically interesting is the relationship between the rules of the game and the player. It is at this juncture that the other elements of gameplay (developer intention, gameworld, player, and community) converge. Sicart, however, does not acknowledge that his view is one very specific way of seeing ethics, but rather posits his view as the universal view supported by philosophical universals.

Matt McCormick, author of “Is It Wrong to Play Violent Video Games” on which Sicart bases much of his work, continually discusses the possible affordances and obscurances his lenses of utilitarianism, deontological, and value ethics frameworks provide. “Value Ethics,” a similar lens to the virtue ethics that Sicart uses, is discussed by McCormick as being egotistical, privileging the interior of a person over all other external factors.

Bonnie Nardi, author of My Life as a Night Elf Priest: An Anthropological Account of World of Warcraft (2010) explores the many ethical issues she must face as she investigates the “peculiarities of human play” (7) inside the MMORPG World of Warcraft (Blizzard, 2003). One aim of her work is to help others understand how video games impact our culture, and this is where ethical concerns about race, gender, and addiction begin to surface. She also explores the morals and stigma that follow someone dedicating large amounts of time to something that isn’t “real” (131). Nardi primarily focuses on this player-virtual world relationship. She then works on situating the player in the world outside of the game to examine the ethical issues that cross the virtual/real world divide such as violence and stereotypes.

Mia Consalvo, professor of at Concordia University in Canada, was one of the first game theorists to directly engage in the question of ethics. In her groundbreaking article, “Rule Sets, Cheating, and Magic Circles: Studying Games and Ethics” (2005), she discusses the importance of studying the ethics of games and of the players interacting with the games. She writes, “Clearly, we need a better understanding of how ethics might be expressed in gameplay situations, and how we can study the ethical frameworks that games offer to players. Research in this area is beginning (Reynolds, 2002), but many interesting questions remain to be asked” (8). She uses active audience theory, which loosely argues that media are never closed and that authorial intent is never complete, in order to ask new questions about the nature of play and games.

From each of these authors we can see parts of Procedural Ethics emerging. Sicart focuses on the relationship of the player to the game as a designed system. McCormick and Consalvo begin to pave the way for the argument that the researcher’s views are crucial. And Nardi forces us to constantly question the divide between real and fantasy and reminds us that our work is not just about “games” as some silly thing, but that games are important parts of the lives of many people. In the next installment, I will go more into procedural ethics and how I see it working on the current landscape of game studies. Plus I’ll add in some sass and razzing of people who I believe are conduct unethical research.