At Sunday’s Oscars, John Legend and Common performed their amazing song, “Glory,” from Selma before ultimately winning the Oscar for Best Original Song. If you haven’t seen the performance yet, it’s a must:

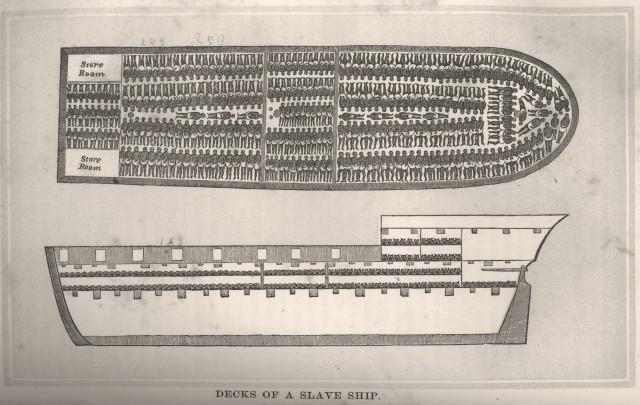

But as powerful as the song is, it’s the acceptance speech (starting at 6:05) that captured my attention on Sunday night. Amidst the common platitudes and thank yous, John Legend had this to say: “It’s an artist’s duty to reflect the times in which we live. We wrote this song for a film that was based on events 50 years ago, but we say that Selma is now because…we know that right now the struggle for freedom and justice is real. We live in the most incarcerated country in the world. There are more black men under correctional control today than were under slavery in 1850. When people are marching with our song, we want to tell you we are with you, we see you, we love you, and march on.”

This is a question that comes up all the time…why demand video games, books, movies, songs that are more accurate, diverse, or representative? Legend’s answer sums it up…our art—fictional or not—reflects our times. More than that, it shapes it. Video games are only one small piece of that art, but they are more immersive than most other forms. There’s a sense of agency in games, where the player takes an active role in shaping the presented narrative (even if that narrative is ultimately beyond their control). In other words, it’s personal.

Maybe that’s why I like simulation games. So many times, games are a form of escape from the “real” world (which is often an argument for allowing unreal conditions. It’s “only” a game, after all). For that reason, simulations might seem like an odd category, considering that they are most effective when they are realistic…yet the Sims is one of EA’s biggest cash cows, raking in millions of dollars with each new edition, and the successful Rollercoaster Tycoon franchise sparked hundreds of tycoon offshoots, from movie theaters to lemonade stands to game development*. These games are simplified forms of the world, yes, but they are realistic. They offer the chance to create Utopian situations, or to “screw up” in glorious fashions and watch the world burn…without any of the real-world consequences.

Sim games are a mini-obsession of mine. I can lose hours in these games, carefully crafting my worlds and micro-managing the details. They are a control-freak’s dream come true. Add in political mindedness, and that is why I picked up Prison Architect.

Prison Architect is Introversion’s indie prison development simulator. While Introversion is a British development company, the game is remarkably reminiscent of the American penitentiary system. Other than the brief tutorial (and the occasional calls from the CEO if you manage to go bankrupt), there is no dialogue in the game. You are given God-like status, complete with a bird’s-eye view of your prison as you shape it and your prisoners’ day-to-day lives.

While the game isn’t overtly political (like many simulators, it’s very hands-off, allowing the player to create their narrative) the game’s well-balanced system highlights some of the stark problems with our prison system: In order to keep from going bankrupt, you often have to pack prisons full of prisoners and keep amenities to a minimum…which results in unhappy prisoners and incredibly unsafe prisons, complete with riots and a daily death toll. In order to keep your prisoners calm, you have to (surprise, surprise) treat them like human beings by giving them adequate food, personal agency through work, access to reform programs, and contact with their families. These measures improve the safety of your prison, as well as lowering the chance of your released prisoners reoffending, but they cost an incredible amount of money. The main challenge of the game is finding the balance between being truly helpful and going broke.

Prison Architect’s main weakness (as far as reflecting American prisons) is its built-in diversity, as is commented on by Kotaku’s Paolo Pedercini. Due to its UK origins, the stark realities of America’s racial prisons are not found in this well-developed game. While this isn’t a flaw in its design (it wasn’t made specifically for this country, after all) it’s problematic for American players who may see this as a representation of our system. First, all of the “head honchos” (the Warden, Foreman, Security Chief, Psychologists, and Accountant) are all white. While all other workers are randomized, these specialized roles will always be Caucasian. Second, the algorithms controlling the diversity of the prison inmates is completely balanced and random. The racial categories are equally represented, as are the randomly generated crimes that appear in their files.

This makes for an odd mixed-message. In some ways, this is the ideal. In a “utopian” prison set-up, race would not impact the population, and (relatively) minor crimes such as drug-related-offenses would not be persecuted as much or more than serious crimes such as murder, rape, and assault. However, in an ideal set-up, the staff would also be as diverse as the inmates. On the other hand, a majority white staff is a reality for both UK and American prisons…but, in America especially, an overwhelming majority of the inmate population is made up of minorities, a fact that is exacerbated by class divides that allow white criminals to have access to more money for bail and legal recourses to combat charges than minorities charged with similar crimes. This game falls short not because it is utopian or too real, but because it can’t seem to decide which way to go.

This makes for an odd mixed-message. In some ways, this is the ideal. In a “utopian” prison set-up, race would not impact the population, and (relatively) minor crimes such as drug-related-offenses would not be persecuted as much or more than serious crimes such as murder, rape, and assault. However, in an ideal set-up, the staff would also be as diverse as the inmates. On the other hand, a majority white staff is a reality for both UK and American prisons…but, in America especially, an overwhelming majority of the inmate population is made up of minorities, a fact that is exacerbated by class divides that allow white criminals to have access to more money for bail and legal recourses to combat charges than minorities charged with similar crimes. This game falls short not because it is utopian or too real, but because it can’t seem to decide which way to go.

Still, I was obsessed. It’s fantastically designed, aesthetically pleasing, and challenging without making you want to throw your desktop or laptop out the window. In fact, I was so enamoured that, when Steam suggested I pick up The Escapists as a funny, similar game, I went for it. While Prison Architect is engaging, it’s very distant. You don’t really have a reason to look at the prisoner files and you are more concerned with overheads than individuals.

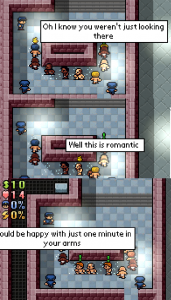

The Escapists offered a different approach. Instead of being in charge, you are a prisoner in the middle of the system, bent on escaping. In the meantime, you have to bide your time, make money by dealing with your fellow inmates, and follow (most of) the rules in order to avoid suspicion. The Escapists actually has dialogue, with little text boxes popping up over the prisoners’ and guards’ heads as they wander the prison. They’re mostly funny, with things like “Unfortunately, our karaoke machine is broken,” and “We punish with love,” or commentary on the awfulness of the food. The mechanics are a bit clunky, but it’s obvious this is meant to be more personal and more light-hearted than Prison Architect, though it shares many of the same mechanics as far as the daily schedule, prisoner life, and interactions with the guards.

But where Prison Architect is a thoughtful, reflective game, The Escapists is disturbing with its carelessness. The warden is white here, too…but so are all of the guards. Your player options are all given default names with racial or class implications (one of the two black player-character options has the default name “Lifer”) and when you get to the shower block, you reach the epitome of humor…prison rape jokes.

But where Prison Architect is a thoughtful, reflective game, The Escapists is disturbing with its carelessness. The warden is white here, too…but so are all of the guards. Your player options are all given default names with racial or class implications (one of the two black player-character options has the default name “Lifer”) and when you get to the shower block, you reach the epitome of humor…prison rape jokes.

For that hour of time (in the game) the pop-ups turn from inane, somewhat silly commentary to a series of variations of “Don’t drop the soap.” Because these are criminals, right? It’s funny. Ha ha.

This is a game…a simulation…and one that’s meant to be fun where Prison Architect is serious, but it’s still a reflection of the real world. Prison rape is a serious, real epidemic…one that disproportionately targets effeminate or weaker inmates and lends to a dehumanization of prisoners in an already oppressively dehumanizing situation. Rape is never about sexual desire (which is something that is often ignored with heterosexual rape). It’s about power, domination, and control.

Even worse, prison rape has been cited as a reason for keeping white criminals out of the penitentiary system. They are minorities in prisons (due to systemic racial biases), which places them in a position of weakness. This has led to judges ruling to keep them out of the system to protect them (a privilege rarely—if ever—afforded to homosexual and/or minority criminals). While I think it’s incredibly important to protect ALL people from rape and abuse, the systemic privileging of whites’ safety over others’ only adds to the racial disparity, increasing the danger for white criminals who are convicted and adding to the harmful stereotypes of minorities as dangerous or worthy of being punished.

The Escapists is “just a game.” It offers some laughs, quite a few challenges, and a light-hearted view of the inside of a prison. Unlike in Prison Architect, no one dies. Fights end with a brief trip to the infirmary and a quick recovery. Rape is just a joke.

Games don’t have to be “real.” They are something else entirely. But to fictionalize serious, life-altering events as humor (or to deny their existence at all) is to add to the ignorance that already exists.

Prison Architect, whatever its flaws, tries to give a window into a real world and real system. The Escapists makes a mockery of something that could have been impactful (even without becoming overtly political).